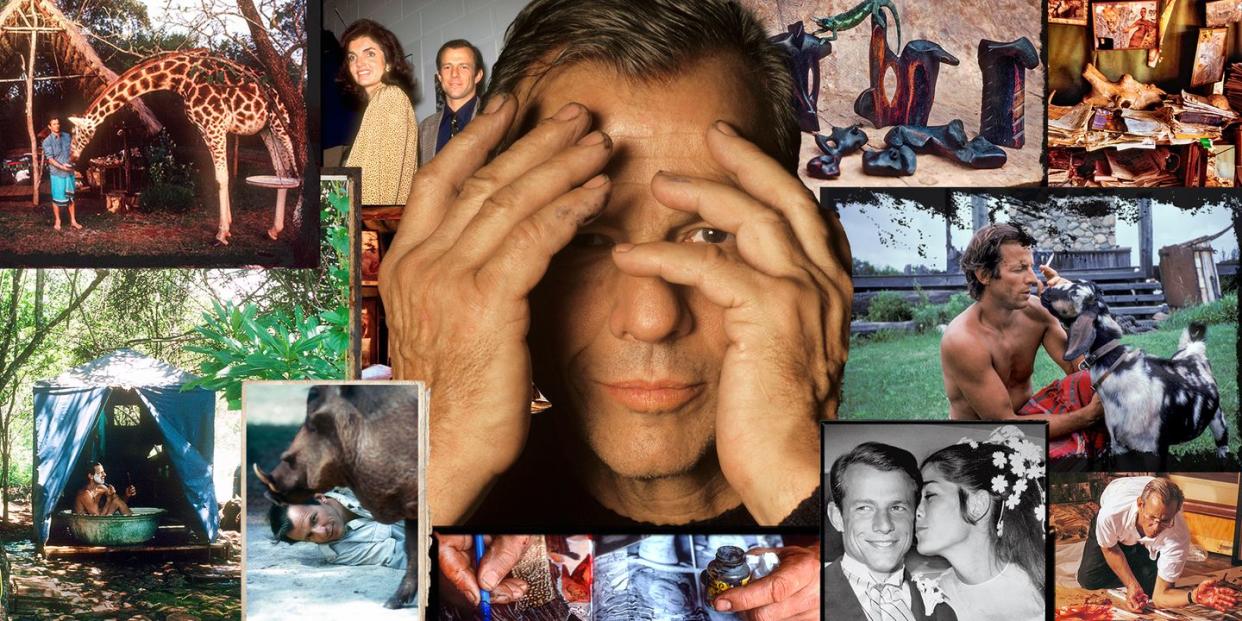

Wild Man: The Life and Times of Peter Beard

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

In March 2020, Peter Beard disappeared into the woods near his Montauk home and, like an old bull elephant, lay down and died (the sort of end, his friends pointed out, he would have wanted). But the fascination with Beard continues, fueled by the expansiveness and contradictions of his life, the ferment around his artistic legacy, and our age old interest in the mysteries of creative inspiration and the lines—so blurred in Beard’s case—between life and art. As Philippe Garner, former head of international photography at Christie’s, put it, “The world doesn’t seem to create characters like that anymore. There’s no room for them now. He was a wonderful spirit. An adventurer. A wild man. And if you bought a Peter Beard, you were buying part of that extraordinary story.” This article is adapted from Wild: The Life of Peter Beard, out this month (St. Martin’s Press).

On September 9, 1996, while on a photo shoot in a remote corner of Kenya’s Masai Mara, an hour’s drive from the closest dirt airstrip, Peter Beard was crushed and gored by a rampant female elephant. It nearly killed him. His spleen was ruptured and his pelvis broken in five places. Seven weeks later—after an agonizing convalescence—he was in Paris. His big one-man show at the Centre National de la Photographie, in the planning for more than a year, was opening on November 6. There was 20,000 square feet of exhibition space to fill. Some artwork had already been shipped over, but many of his major photographic pieces still required the intense marking, filigree writing, and streaks of blood (some his own, some from the nearest butcher) that would transform them into intense, multilayered original Beard artworks.

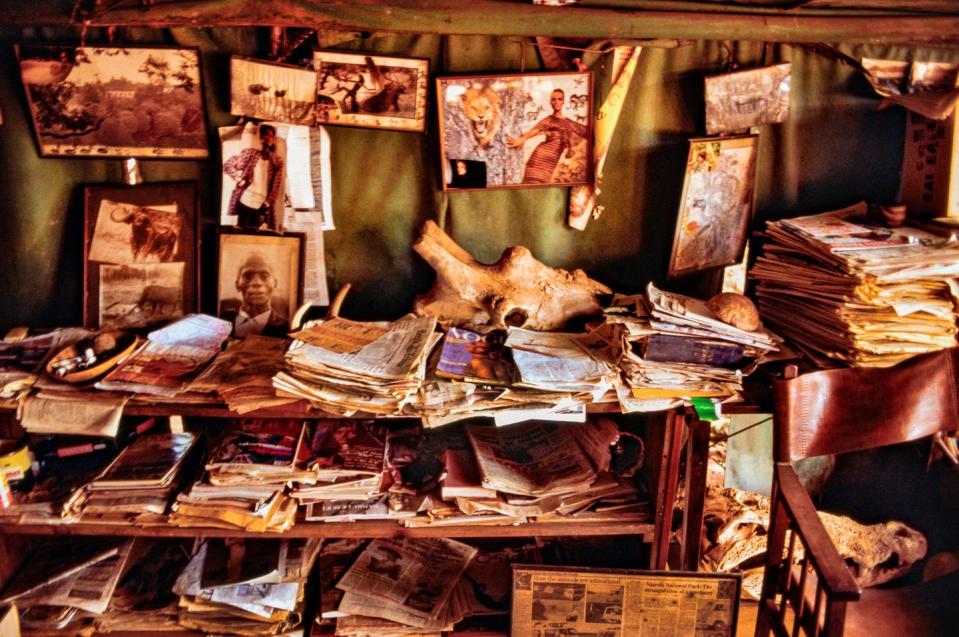

The gallery, in the Palais de Rothschild, provided the injured artist with a mattress. Beard lay on the floor, hand-working the prints, wielding tubes of glue, cuttings, and the paraphernalia of his collages in a blur of artistic frenzy. Then he and his New York gallerist, Peter Tunney, went to work on the displays. One, Dead Elephant Swimming Pool, consisted of two floor panels of six-by-eight-foot aerial black-and-white photographs of dead elephants from The End of the Game, Beard’s powerful 1965 paean to Africa’s disappearing wilderness. Surrounded by 2,000 small cutouts of more dead elephants, meticulously glued down, they were covered with plexiglass—so visitors could walk across the carcasses of the creatures. A 20-foot-long display case in the middle of one room held a selection of the image-laden diaries that Beard had been keeping since he was a boy.

Against the odds, the retrospective opened on time. And it was attended by multitudes: friends, acquaintances, assorted followers, celebrities from around the world. The Dinesens, relatives of Karen Blixen, came from Copenhagen. (Out of Africa, which Beard had read at age 16, was the intellectual and emotional springboard for his African adventures.) The habitués of Hog Ranch, Beard’s 40-acre Kenya retreat and salon-in-the-bush, came from Nairobi. The rock star/photographer Bryan Adams, as well as David Bowie and his wife Iman (whom Beard had made famous 20 years earlier), attended—as it seems did every model within a 100-mile radius of Paris. The show ran until January 20, and, according to Tunney, it broke every attendance record.

Similarly eventful, chaotic exhibitions were held over the following years across Europe and the U.S., with Beard invariably at the center of the action, sprawled on the floor working on pieces, photographing scantily clad subjects in front of art-filled walls, or just holding court. Yet for all that, there was something elusive, unknowable about the man with the movie star looks. Pianist and bandleader Peter Duchin—Beard’s lifelong friend, Yale classmate, and fellow society rebel—confirms this enigmatic quality. He vividly remembers sitting stark naked in the steam room at the New York Racquet Club when Peter’s father, Anson Beard III, sat down beside him. “He asked me how I was. I said how nice it was to see him,” Duchin says. “Then he looked me in the eyes and said, ‘Could you explain my son Peter to me?’ I said, ‘I can tell you about Anson Jr. and Sam [Beard’s older and younger brothers]. But Peter? That’s a bit too difficult.’ ”

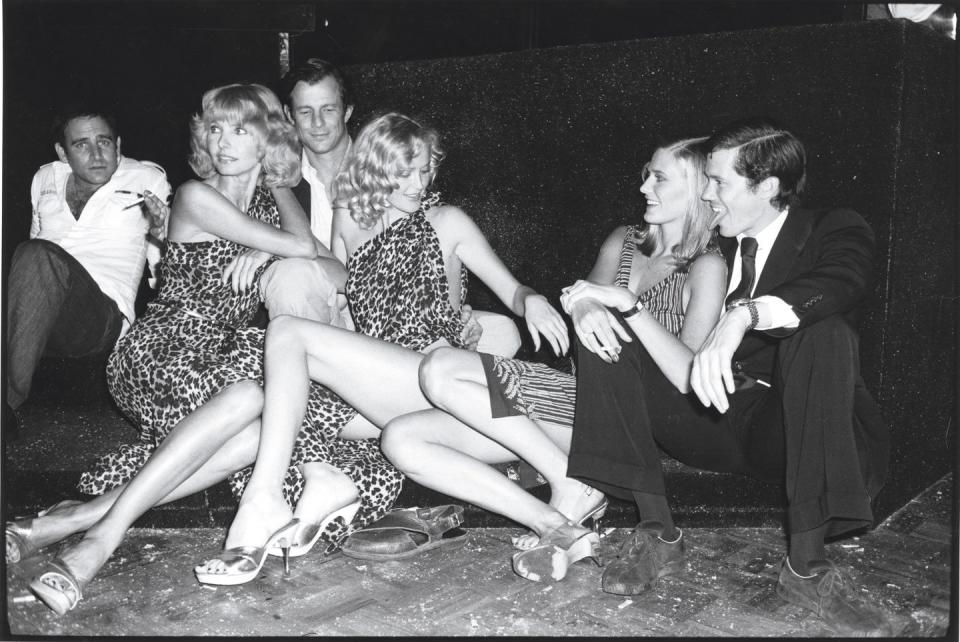

Peter Beard was an elusive creature, but one with a well-documented upbringing. After privileged early years (in Manhattan, the Pomfret boarding school in Connecticut, and Yale), he accelerated like a freight train through the decades, hunting wild animals in Africa, taking dramatic photographs of exquisite women, speaking out for the preservation of wilderness, celebrity friend–hopping, clubbing in Manhattan’s nocturnal dens, effortlessly seducing wherever he went, and making art.

His main theaters of operation, and studios, were Hog Ranch, Manhattan, and Thunderbolt Ranch, his six-acre spread in Montauk. It was a gilded path, one fueled by the consumption of industrial quantities of drugs. He often said, privately and in print, that he preferred to be “pleasantly pixilated,” and so he was, for all his adult life. Marijuana, ecstasy, cocaine, LSD, peyote, crack—he did them all. But he never appeared out of control. The pharmaceutical magic carpet he rode seemed to distance him from the harsh vagaries of a world of which he did not instinctively approve, and allowed him to fully express his heady, freewheeling mix of art and life. Or maybe not: One night in Tunney’s gallery, The Time Is Always Now, which served as Beard’s artistic base in his prolific 1990s, Beard and Tunney were rummaging through boxes of Beard’s collected detritus (he was a hoarder of everything that passed before him in his life). They happened upon a folded scrap of paper dated 1949. On it, written in an 11-year-old’s hand, were the following words: “Get adventure and riches. Make yourself famous. PS All prisons empty.” There it was: a plan for the colorful, disruptive, anarchic lifestyle for which he became celebrated and for which his explosive, collagist art became an expression.

NATURE’S PROPHET

Soon after his graduation from Yale in 1961, Beard found himself working in the Kenyan wilderness, reigniting his African romance, tracking animals, documenting the annihilation of wildlife. Those years in East Africa coincided with the end of empire, and he milked it for all it was worth. Nobody else straddled the two worlds of postcolonial Africa and celebrity-obsessed modern America with such facility, managing to make them sound part of the same thing. Somehow, albeit in a rather improvisational and sometimes random manner, Beard placed himself at the center of the African conservation debate. His standard harangues concerned the continent’s burgeoning human population, the postcolonial mismanagement of its wildlife, and the inappropriate, sentimental interference in African affairs by Western do-gooders, who, he was wont to say, “are looking to buy an elephant a drink” and who played an increasingly significant role in the continent’s faltering progress in the years since the Europeans packed up their tents and went home. “Lords of poverty,” he called philanthropists, repeatedly referring to the aid industry as the “alms race.”

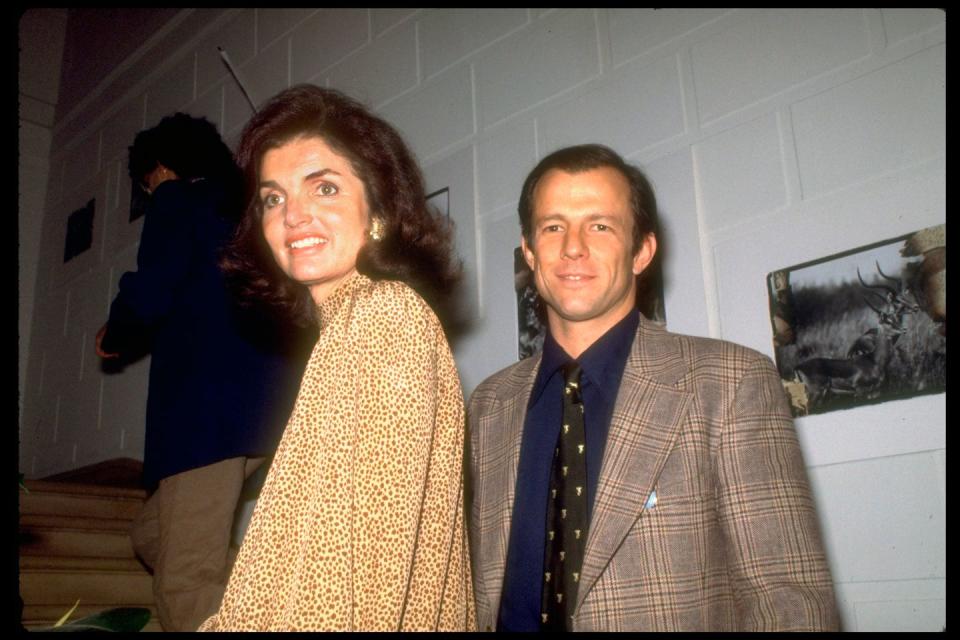

What Beard said, if you didn’t listen too closely, had a fiery, impassioned logic to it. And people listened. In addition to Andy Warhol and Francis Bacon (who, plainly enchanted by this handsome man, painted nine major portraits of Beard), his well-publicized circle of friends included Mick Jagger, Truman Capote, Jackie Onassis, and Lee Radziwill (who was his lover in the mid-’70s). They paid attention not because of the heft of Beard’s philosophical or sociopolitical aperçus, but because he was beautiful, dramatic, crazy, and an important social cog in the New York club scene.

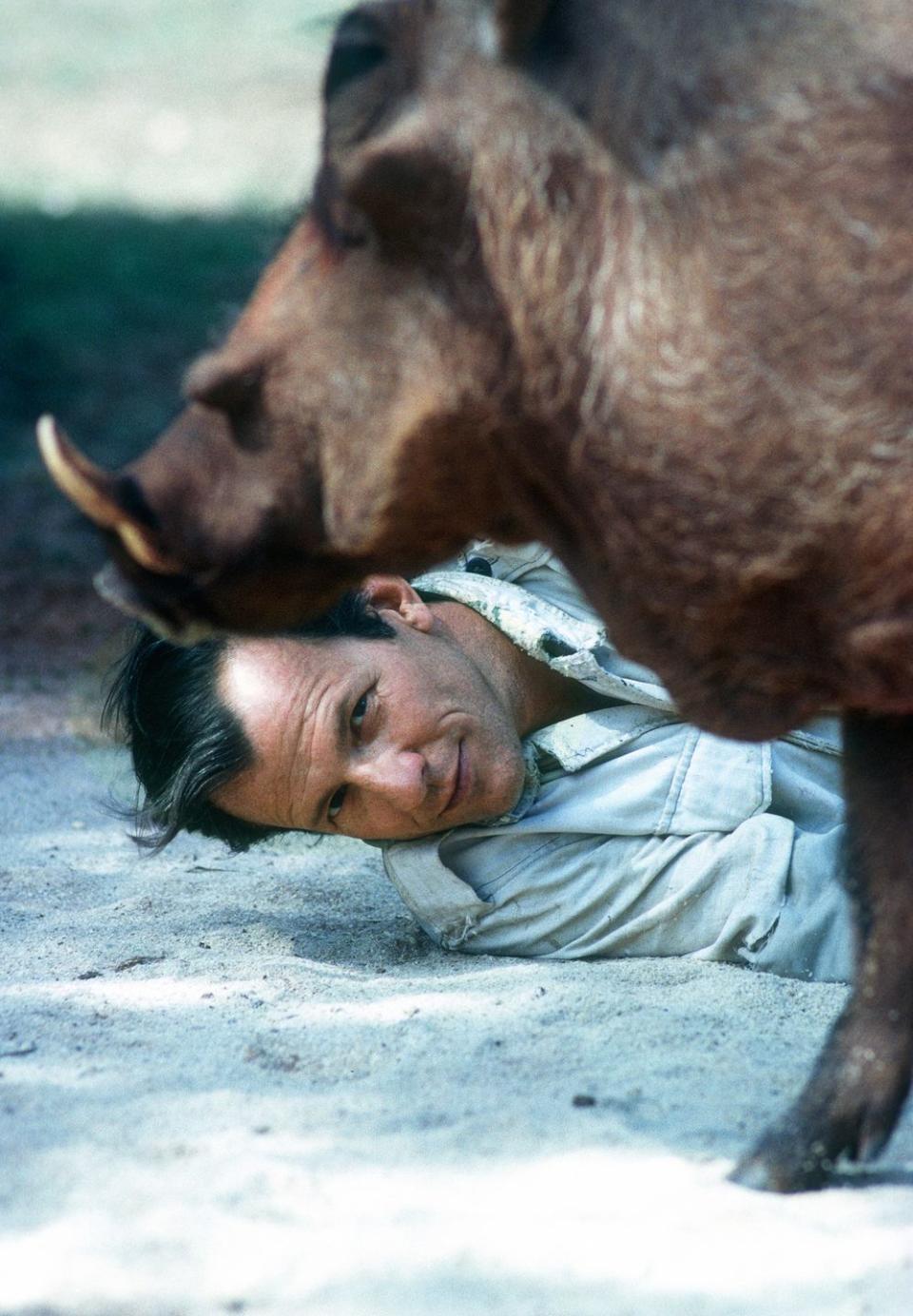

But Beard’s passion ruffled feathers in the African wildlife community, particularly among conservation’s heavy hitters. What started out as a fascination with the adventurous young American arriviste with Hollywood looks who dressed like a hobo (he was invariably clad in an East African kikoi and Pitamber Khoda sandals—even later, during bitter New York winters) soon turned to impatience with his reckless behavior when around wild animals.

He was banned from Tsavo National Park by his former friend David Sheldrick, the park’s warden, who frequently warned Beard that his insistence on close encounters with dangerous animals would end badly. When it finally did, on that fateful day in 1996, his close friends gathered around, but many of Kenya’s Africa hands just shrugged and said it had been a long time coming.

ENFANT TERRIBLE

Beard grew up in late-1950s America but would no more have raved about Elvis or Little Richard or Buddy Holly than he would have considered joining a celibate religious order. He was a WASP from another era in another sense, too. Today it would be easy to see him as a racist, sexist, privileged white male. And some do. To the racism charge, his defenders reply: He was married for 35 years to a woman of Asian and Muslim heritage, his widow, Nejma Khanum Beard, whom he’d met in Kenya. When asked in the days after his death whether he was racist, his longtime mistress, the mixed-race model Maureen Gallagher (subject of probably his most famous photograph, The Night Feeder, shot at Hog Ranch), burst out laughing: “If he had been, he certainly wouldn’t have dated me.” One of his Kenyan friends remarked that rather than being a racist, Beard was in fact a misanthrope, an equal opportunity abuser of homo sapiens who he thought were doing such a terrible job looking after the planet.

He was indisputably, however, a serial philanderer. “I have never seen any other man have that effect on women,” says Nell Campbell, the 1980s nightclub impresario. “There was always a gaggle around him. He was like Rudolf Valentino.” He was lean, athletic, with a clipped 1950s haircut (no hippie tresses for him), high cheekbones, and bright, alert eyes always on the lookout for new adventure. His physical imperfections—large ears, big, gnarled hands, and sprawling feet—just intensified his appeal. The parade of women may be seen today as evidence of a sexual predator at work. Yet these accusations are firmly rejected by the women he dated. Virtually without exception his female friends and lovers describe him as a thoughtful, kind, and caring paramour (albeit one with a very clear view of marriage, which was to ignore its constraints), and they maintained affectionate relationships with him long after their various affairs had ended.

Cheryl Tiegs, his second wife, who prior to their divorce spent four days angrily cutting out with an X-Acto knife every image of herself from the Beard photo archive, says of him today, “he was the love of my life.” However, some lifelong acquaintances have suggested that Beard, despite professing adoration to a string of women in letters and endless phone calls, never really loved any of them—that the sociopath in him permitted just one true love, and that was Zara, his only child (with Nejma).

THE BEARD BEQUEST

Beard’s artistic legacy remains difficult to assess. Art historian Drew Hammond believes that “Beard reinvented photography as an art form in the most complex, philosophical manner—whether consciously or not, it doesn’t matter. What is important is that he used the photograph as an image field for another work of art.” However, his production of works was often based on a simple business model: the need to pay bar and restaurant tabs, not to mention drug dealers. In the eyes of some art historians and gallerists, the abundance of Beard’s work has diminished its value. The dealer Philippe Garner says that as much as he admired Beard as a significant artist, what he found “troubling is not so much that he was prolific, but sometimes you had the sense that he was lazy…and that he would let out lesser works to pay bills. He should have been more disciplined about what he released, and he’d have been richer for it. But could anyone have had that conversation with him? I don’t think so. How much is out there? Not enough to satisfy what I imagine will continue to be the demand.”

Denise Bethel, former chair of Sotheby’s photography department who for 25 years played a key role in pushing photography’s transition from camera club collectible to legitimate fine art, has been a Beard fan “since I bought The End of the Game, so for me he will stand the test of time. But many auctions now are virtual. Live auctions will continue for big painting sales that bring in $100 million…but I don’t know how you can appreciate a great Peter Beard artwork virtually.” The value of Beard’s work has risen steadily. By 2010 his pieces were selling for $60,000 to $70,000. In 2012 his Orphan Cheetah Triptych (1968) went for $662,000 at a Christie’s auction in New York.

Since the 1996 elephant attack, the business side of Beard’s life has been run by the long-suffering Nejma, who at the time ruthlessly threw overboard his gallerist, Peter Tunney, and agent, Peter Riva. (“She will be my Jacqueline, the governess,” Beard declared, referring to Picasso’s second wife, Jacqueline Roque, who took control of the master’s “late Picasso” output.) After Beard died (at 82), one of the people Nejma phoned to discuss his art legacy was Michael Hoppen, the London gallerist who had played a significant part in making his name in the UK. “Museums did not seem to be interested in Peter’s work,” Hoppen says. “Of course, he should be in museums. But when he was alive Peter wasn’t interested—he didn’t regard that as confirmation of his talent.”

Then there are Beard’s diaries, bulging, voluptuous collections in which he chronicled his raucous life in the most lurid, vivacious form. Beard was offhand about the diaries, telling journalist Edward Behr, “I’ve never thought too much about it. It just accumulates, a little like dirt.” Yet Village Voice critic Owen Edwards, one of Beard’s most astute observers in the 1970s, described them as “a combination of adolescent daydreaming, fiendish detritus…frantic tangible psychotherapy, and visual novas.” They could stand “on future bookshelves next to Pepys, Kafka, and Woolf. Not as literature, but as the copious archaeology of a particular mind.”

Some have been displayed in international exhibitions, and 15 years ago Bernard Sabrier, a Swiss collector, offered the Peter Beard Studio $1 million for a diary and was turned down. It is estimated that Nejma has 30, 40, maybe even 50 of them—nobody is quite sure—in a safe at Crozier Fine Arts Storage in New York. Hoppen also believes that the Beard photographic archive, likewise controlled by Nejma, is an untapped trove, with many valuable images to be unearthed, some never seen or printed before. How Nejma chooses to share it all will probably determine her errant husband’s artistic legacy. As yet she has not declared her intentions.

From Wild: The Life of Peter Beard: Photographer, Adventurer, Lover by Graham Boynton. © 2022 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press

This story appears in the October 2022 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like