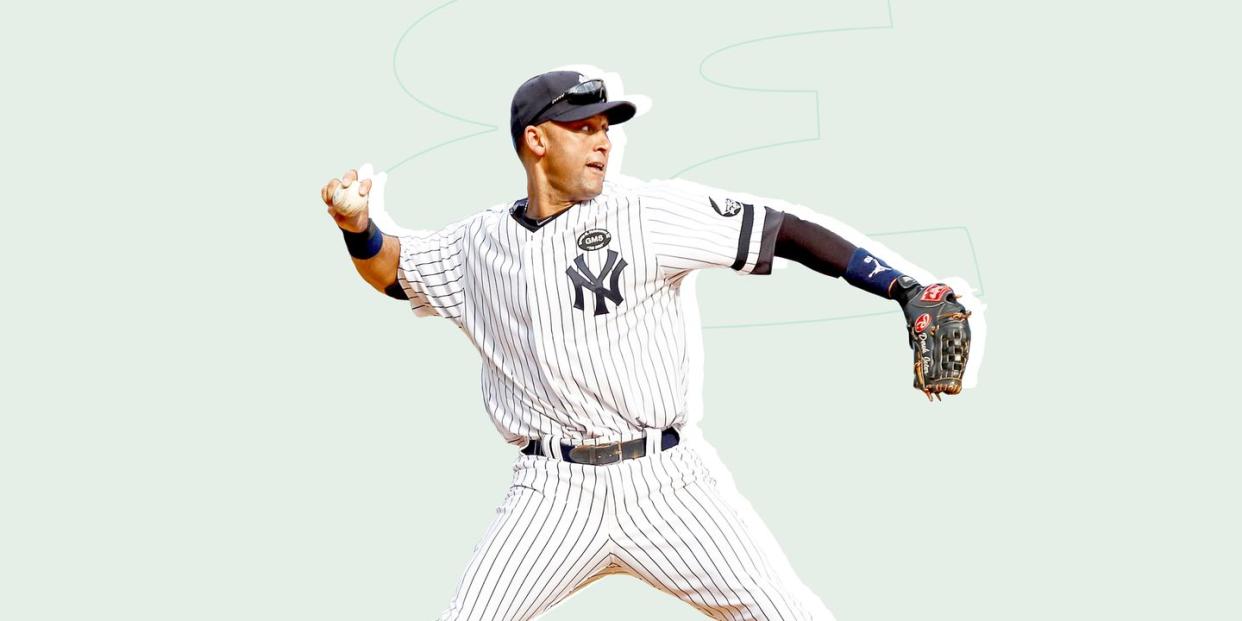

Where Have You Gone, Derek Jeter?

It’s been eight years since Derek Jeter’s final season as a professional ballplayer and he’s softly faded to the margins of public life. Sure, there was the forgettable four-year run as CEO of the Miami Marlins (which took some of the shine of his pristine image), but unless you are a baseball fan, he’s all but disappeared.

Unlike his old rival/teammate/rival, Alex Rodriguez, Jeter’s shown little interest in showbusiness—announcing games or being an in-studio talking head, not for him. Which is why Jeter’s sudden presence on Twitter last month raised eyebrows. Why would this famously guarded man jump into the unwieldy world of social media, which can easily reduce even the coolest person into an insufferable asshole?

Et tu, DJ? And why now? Well, it’s not necessarily because Jeter felt the urge to be seen, heard, or understood, it’s because he’s on board to promote The Captain, a seven-part ESPN docuseries co-produced by Spike Lee and Jeter’s longtime agent, Casey Close. The first episode of a a high-gloss career highlight reel, The Captain, debuts on ESPN after this Monday’s Home Run Derby. It’s The Last Dance without the tension. That said, it's an intriguing look at Jeter’s career, which began when tabloid newspapers still battled daily for headlines and ended in the age of social media. Throughout, Jeter remained hidden (protected is more like it) in plain sight.

Along with Rodriguez, Jeter is the last baseball celebrity. (Together, they were the last baseball soap opera.) Beyond all the accolades, and puffed-up Yankee self-importance, Jeter left behind a blueprint for the modern player to navigate the perils of fame: be professional, accountable, and bland. Mike Trout is one of the greatest players of his time yet you don’t know anything about him; ditto, Aaron Judge who plays under the same intense scrutiny as did Jeter. Treat the media like another opposing team. Never crack, never give them a story. Be cordial, accountable, speak in cliches. A modern-day Joe DiMaggio, famous for wariness and control, Jeter vigilantly maintained his privacy in the glare of the New York spotlight for almost two decades. We were invited to look but not touch. Jeter’s job was to play baseball, everything else was distraction. He didn’t need to be known, didn’t care to share his opinion.

Which is what makes his appearance on Twitter dispiriting. But Jeter has always been dutiful and he’s got a product to sell. The documentary will not likely move anyone other than Yankee fans and the most die-hard seamheads, but in it, Jeter reveals more of himself than we’ve yet seen. As you would expect, this is skillfully-crafted hagiography, with high production values (hey, they even use background instrumentals by DJ Premier), and buy-in from Jeter, his friends and family. It offers the patina of intimacy. That said, Jeter explains his approach to the media, and his longtime relationship with Rodriguez, with directness and a dose of good humor. He may be necessarily mistrustful but he also comes across as having a lot of common sense. From clarifying his feelings about race to laughing off the infamous NY Post report that he gave gift baskets to his love conquests, Jeter comes across as practical, droll, and sharp.

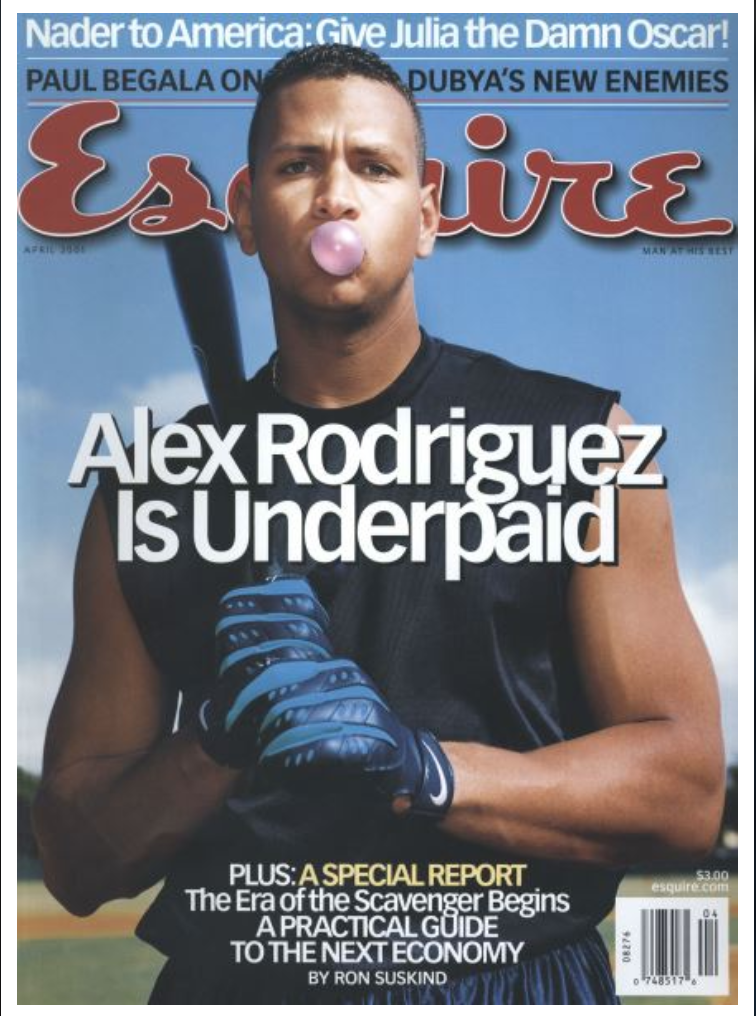

It was Scott Raab’s 2001 Esquire profile of Rodriguez that ended the A-Rod/Jeter bromance. Truth is, what Rodriguez said about Jeter was not wrong—at that point in his career, Jeter was on of several stars on the Yanks, and not the Babe Ruth/Mickey Mantle caliber of superstar—it’s that he said anything at all. For someone like Jeter who never wanted to add complications to his world, Rodriguez expressing himself to a magazine writer—lowest of the low!—violated the code: Keep your mouth shut and don’t give the vultures anything to feast on.

Rodriguez, an outsized talent with a penchant for self-immolation, was arguably the best player in the game but he was also an insecure mess; the more he needed to be loved, the more the fans disliked him. They can smell desperation and while New York fans loves neurotics, they don’t want their superstars to be neurotic. Jeter’s showmanship did not extend beyond the field. He played during the last era when newspapers—print papers—fought daily for back page dominance. If you’ve never seen the New York media swarm the clubhouse at Yankee Stadium, well, it’s a scene. There are plenty of sharp elbows, sideways glances, and general aggression. It has all the charm of a Glengarry Glen Ross reunion special.

Jeter seemed born for the big moment, and as the centerpiece of the game’s last true dynasty (there have not been back-to-back World Series champions sine the Yankees 1998-’00 three-peat), he authored more legendary highlights than virtually any player of his era. That doesn’t mean he was the best player, just the one with a lopsided amount of attention.

Jeter was overrated because of his exposure; many fans grew sick of hearing about Saint Derek. Still, Jeter managed to escape scandal, which is not something you cannot say for Michael Jordan (gambling), Kobe Bryant (sexual assault allegations), or Tiger Woods (overall shittiness). For many of his longtime adversaries in the New York press, Jeter’s ability to stay clean that may be his crowning achievement. But as the doc makes clear, even Saints need some good luck; Jeter was this close to being at Club New York one night in 1999 with Puffy and J-Lo when shots rang out. He and his crew, at the last minute, decided not to attend. And when the Yankees meddling owner George Steinbrenner started giving Jeter grief in public about Jeter’s nightlife, Jeter enlisted the Boss to do a credit card commercial with him and lampoon the entire episode. Like we said, smart cookie.

Jeter’s smirk, cockiness, and his affiliation with the Yankees took him out of the running as “the face of the game”—he didn’t have an outsized talent or mega-watt smile such as Ken Griffey Jr. But in many ways he became the game’s ultimate role model. He was a good son from a tightly-knit family. A guy you want to name your son after.

To watch Jeter on the field was to see a performer completely comfortable in his own skin. We could watch him, observe him, but never know him. He didn’t share of himself that way. This reserve made him more admirable than lovable.

The one quality about Jeter’s game that went relatively underreported was just how much he enjoyed himself playing. For a guy who possessed the humorless drive to win, was dullsville as a quote, Jeter was never morose on the field. He rarely argued with umpires, did not get into major riffs with other players. No, Jeter smiled and laughed often—when he was stepping in the batter’s box, or greeting a runner at second base. He’s what is known in baseball circles as a “gamer,” someone who doesn’t get lazy during a regular season game in June, or tight during the seventh game of the Whirled Serious in October. To watch Jeter play baseball was to see a man enjoying himself, free, expressive (and likely profane), in a way we never experienced him otherwise.

Look but don’t touch. This is how you do it.

You Might Also Like