‘I Thought All Pilots Were Black’: How Two Families Made Flying a Way of Life Across Generations

When Jesse D. Hayes IV was a child in 1960s Texas, his family would skip over the segregated American South by flying their own plane to see relatives in Gary, Indiana. The Mooney M20 shortened the trip by several days but also allowed them to avoid the risk of being denied service at hotels, restaurants or gas stations.

Less than 3 percent of pilots are Black, according to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, but for some families, aviation seems to be embedded in their DNA.

More from Robb Report

“I grew up in the back of an airplane,” Hayes, a former Air Force pilot and Boeing engineer, tells Robb Report. “For a good part of my life, I thought all pilots were Black. That was all I knew.”

His father, Jesse D. Hayes Jr.—the first black ophthalmologist in Texas, according to Hayes—showed an aptitude for engineering as a student, but was “encouraged to pursue medicine because it was one of one of the few acceptable careers for Black folks to serve their segregated community.”

Instead, his father became an amateur pilot after meeting three Tuskegee Airmen, the legendary group of African-Americans who flew combat missions during World War II. Hayes Jr. went on to own several aircraft and become a leader in the flying community—both as the founding president of the Bronze Eagles Flying Club in 1968 and as a co-creator of the Operation Skyhook flying competition for Black pilots.

By the time Hayes was a teenager, flying was second nature. He took his first solo flight in a Piper Cherokee 140 from Houston Hobby Airport as a 15-year-old Eagle Scout.

He recalls saying to his father, who was inducted into the Black Pilots of America Hall of Fame last year, “‘I don’t understand why you’re part of so many organizations for Black people.’ My father said, ‘Well, it’s as simple as understanding that you’ve never been told you can’t do something because you’re Black.’”

For the last decade, Hayes has been helping diversify the aerospace industry as founder and president of the Mukilteo, Washington-based Red-Tailed Hawks Flying Club, a chapter of the non-profit Black Pilots of America that helps students earn scholarships and access flight training. The club has become the largest in the US, responsible for introducing over 5,000 underrepresented youths to the world of aviation. “I’m trying to build something that will be around long after me so this is, prayerfully, a long-term, longstanding institution in the Pacific Northwest,” he says.

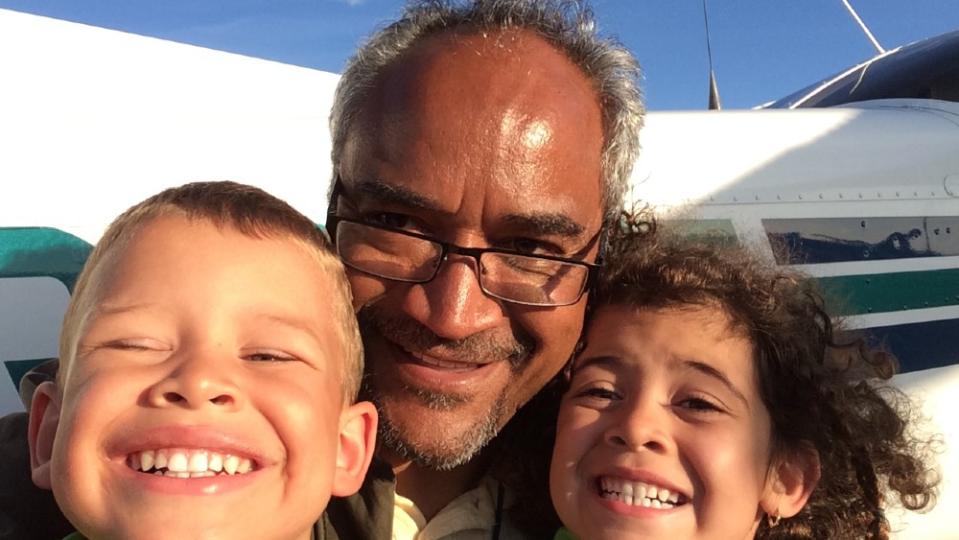

Beyond teaching others, Hayes has passed his love of flying to his children. Two of Hayes’ six children are involved with aviation. Eventually, he hopes his 11-year-old grandchildren, Harper and Jesse D. Hayes VI, will continue the tradition.

Dr. Audrey Hodge, who has known Hayes since they were children attending an annual Memorial Day flying event, is also creating an aviation lineage. Her father, a military pilot and Tuskegee Institute graduate, was instrumental in the development of the Black Pilots of America.

When she was 10, Charles “Chief” Alfred Anderson, the eminent Tuskegee Airmen instructor, taught Hodge to fly in a Cessna 172. Anderson, who taught himself to fly in the 1920s, is a legend in aviation history. In 1932, he was the first Black American to earn a commercial pilot’s license and, a year later, the first Black pilot to crisscross the country, often navigating with roadmaps.

Anderson went on to become lead trainer for the Tuskegee Airmen, the Black pilots who contributed to the Allied victory in World War II. During that time, Anderson flew then-First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt around during her visit to the War Training Service in Tuskegee.

Hodge, who owns a Cessna 182 and volunteers as a flight instructor, is extending the family legacy. Her twentysomething daughters, Alicia and Alani, who have “have been flying ever since they could see over the instrument panel,” have their student pilot licenses. She also gave Chief Anderson’s grandson his first airplane ride during the ceremony commemorating the hangar in Tuskegee named in Anderson’s honor.

“I took him up on a flight over the city of Tuskegee and let him experience holding the controls,” she says. “That was an eerie feeling, given the historic nature of Tuskegee and my connection with Chief Anderson, and one of the highlights of my flying career.”

Best of Robb Report

The 2024 Chevy C8 Corvette: Everything We Know About the Powerful Mid-Engine Beast

The 15 Best Travel Trailers for Camping and Road-Tripping Adventures

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.