The enduring Dukha, one of the last nomadic reindeer herders in Mongolia

The four-wheel drive my friend and I were on hit a bump, and for the briefest moment, we were airborne, before gravity drew us down unceremoniously onto our seats. Shaken but not stirred, we buckled up for the journey to find and spend some time with the Dukha, one of the last few groups of nomadic reindeer herders in the world.

The Dukha live alongside reindeer in the northern Khövsgöl aimag of Mongolia. The aimag is further split into the East and West Taiga, with the entire area characterised by an awe-inspiring combination of infinite steppes, pine trees, rolling hills, mountains, steep, rocky slopes, lakes and winding rivers of varying depths.

Thousands of years before, the Dukha dwell in Tuva, a republic southwest of Russia. Due to forced collectivisation and fear of being drafted into the Soviet war they did not ask for, they moved closer to Mongolia, eventually gaining Mongolian citizenship. Their nomadic movement is limited within the area now known as the Tsaagan Nuur (”White Lake”).

Fast forward a century, and a declining community of less than 30 Dukha Tsaatan households now occupy West Taiga. Due to its diverse topography, vehicles steer sensibly clear of the area, normally traversed on horseback by the locals and increasingly, on motorbikes.

Our personal bouncy castle (read: the 4WD) could only bring us as far as a Mongolian family’s camp located at the edge of the Tsaagan Nuur, where we would rent horses from. An additional horse guide was needed to guide us through the next leg of our expedition and help provide translations. From there, it would take around one to two days to locate a Dukha family.

After one and a half days of cantering through steepe and fields of wildflowers, crossing rivers and trotting up rocky slopes, we entered a dramatic and Lord-of-the-Ring-esque landscape.

It’s the start of summer, but snow still strings the hills, while the nearby lake hasn’t thawed. The weather can get chilly due to the subarctic nature of the region but the relentless afternoon sun keeps the weather at a cool 16-19 degrees Celsius. Mongolia receives the most rain during summer, so travellers need to be prepared for sun, rain or hail at a moment’s notice.

It didn’t take long for our guides to lead us to yurts, the telltale sign of a Dukha’s dwelling.

Before long, we found ourselves swept into the life of the modern Dukha, who struggle between keeping their traditions alive and adapting to the world that’s whizzing by them. Here’s a little insight.

An entire family in a single yurt

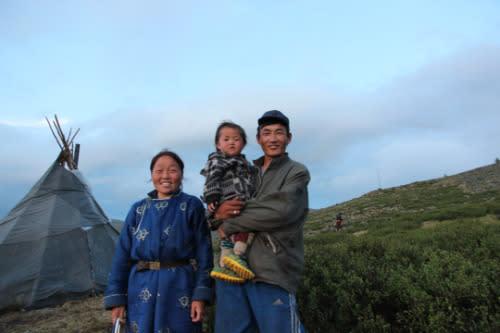

An entire household usually occupies one yurt; in this camp, five households coexist peacefully. Pictured below, our host Magsar, his wife Shinae and their daughters Nara and Sara make up the young family who allowed us to stay in their yurt for the night.

Nara and Sara, which means sun and moon respectively in their traditional tongue, behaved just as their name suggests. Nara (in yellow) is a bright ray of sunshine who is always in the centre of attention—teasing, demanding, jumping into a picture at any chance and laughing at anything. Younger Sara (in green) is more shy and prefers playing with rocks quietly in a corner, hiding behind her sister and snuggling in the bosom of her father.

Curing reindeer meat on strings

The first thing we saw when we entered their yurt was meat being smoked and cured on strings. Traditionally, what set the Dukha apart from all the other reindeer-herding culture in the world was the fact that they do not eat their meat because the reindeer is seen as part of the family, though the hide and leather could be used to craft clothes, belts and boots. It’s a bit like refusing to eat your uncle and aunt, but being okay with wearing them.

Times have changed since then, and meat is important to survive the -50 degrees Celsius cold Mongolian winter. Our 20-year-old guide Shagai also informed us that Mongolians in general believe in letting animals lead a full lifespan before being slaughtered, a decision likely to be influenced by their religious relationship with nature.

Riding reindeer at a young age, stirrups not needed

It’s not difficult to find young children racing past us on reindeer-back, shouting “Chu! Chu!” as they slap the reindeer’s hind to make them go faster. Younger toddlers are placed behind their older siblings, and before long, they too will be able to ride the reindeer confidently.

English lessons for the children

Supported by a government initiative, children and teens get English lessons from a teacher who lives near their camp. Every day, Granny helps some of the younger kids onto the reindeer before they ride off to the teacher’s place, around one hour from their camp.

Protective of their reindeer herds

We arrived just after the calves were just born, and the period during which mama reindeers tend to be overprotective prevented us from getting too near to the herd. Sneakily, we inch slowly towards some of the reindeer, only for the local teen to step in to protect us from them (or maybe it’s the other way round).

The reindeer’s home

Reindeer spend the entire day grazing, roaming far till evening when the men chase after them on horses and herd them back to camp. Gone were the days when each household owned hundreds of reindeer, as forced collectivization in the communism era in Tuva greatly decimated the reindeer’s population in each household.

The Mongolian government has stepped in to import reindeer from nearby regions in order to increase the gene pool of the reindeer, and ensure continuity of the reindeer-herding culture, but nowadays it’s still hard to see any average Dukha household own more than 20 reindeer.

Carving out souvenirs made from reindeer antlers

To supplement his income, our host carved statues out of reindeer antlers to sell to visitors. Selling handmade souvenirs helps the Dukha community earn extra cash to support their families to procure additional rations and equipment that would ease the tough condition of life in the taiga. We understood from him that they receive around a hundred tourists a year, particularly during summer.

Neighbours coming over for a traditional Mongolian card game

On the second day of our stay, neighbouring nomads arrived on horseback to play a traditional card game which bears similarity to poker. The women sat around chatting while the men smoked and played cards.

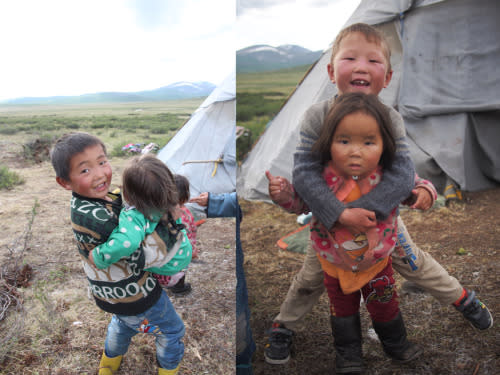

The Dukha cherubs

One of the most rewarding experiences, apart from gaining an insight into how the Dukha live from day to day, was mingling with the free-spirited children of the taiga. They embody the resilience of a race that has survived thousands of years in some of the world’s remotest and coldest regions.

It’s hard to tell if the children will continue the Dukha’s way of life as too many from each generation have given up the rough uncertainty of nomadic living to assimilate into city life.

But when one of them pulled my hand towards the reindeer, excitedly chattering to me in his native tongue, while another handed me a fist full of the stones she’s sharpened, I cannot thank my lucky stars enough that I’ve had a chance to be there, however brief, in the enduring life of the Dukha.

Photo: Nicole Ang

Photo: Nicole Ang