The Supreme Court Gutted Miranda Rights. Here's What That Means Now.

“. . . nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

—Fifth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution

One late night in 1997, youthful drug-dealing me was driving to dinner with a young woman in tow when the police pulled me over, so they claimed, for failing to wear a seatbelt. A pair of officers huffed up on both sides of my Honda with their flashlights beaming, brightness that revealed the not-so-hidden strap I kept under my dashboard for protection. “He’s got a gun! He’s got a gun!” they screamed, ordered us out of my ride, and proceeded to search it, whereupon they found several grams of crack in a baggie bag beneath my seat.

They slammed on handcuffs, stuffed me in the back seat of their squad car, and—sometime before or after reading my Miranda rights—prodded me: “Just tell us whose dope it is. We know it isn’t yours. Just tell us whose it is and you can make this a whole lot easier on yourself.” At the precinct, they placed me in an interrogation room for hours that might as well have been eternity. During that forever, a detective strolled inside and—no counsel present—pressed me once more to snitch on the guys whose dope it really was, intel he said would make my all-but-assured stern punishment less so.

Me lying across a hard bench in a dim room. Cuffs biting my wrists to blood. Pulse loud as gunshots in my temples. The rest of my life a low sky of ominous clouds and this white man with a badge and badgering questions my only hope of Atlas. How easy it would’ve been to tattle to save myself—for the cop’s pressure to force me into making things exponentially, critically worse for myself and others.

Who knows what might’ve happened with rougher tactics, if I’d never been read my rights at all?

But on God, ain’t no snitching over this way, an ethic buttressed by the first line of the Miranda warning. (In the end, I was convicted of distribution of a controlled substance and sentenced to sixteen months in state prison. And for the record, that arrest was the first and last damn time I’ve been Mirandized.)

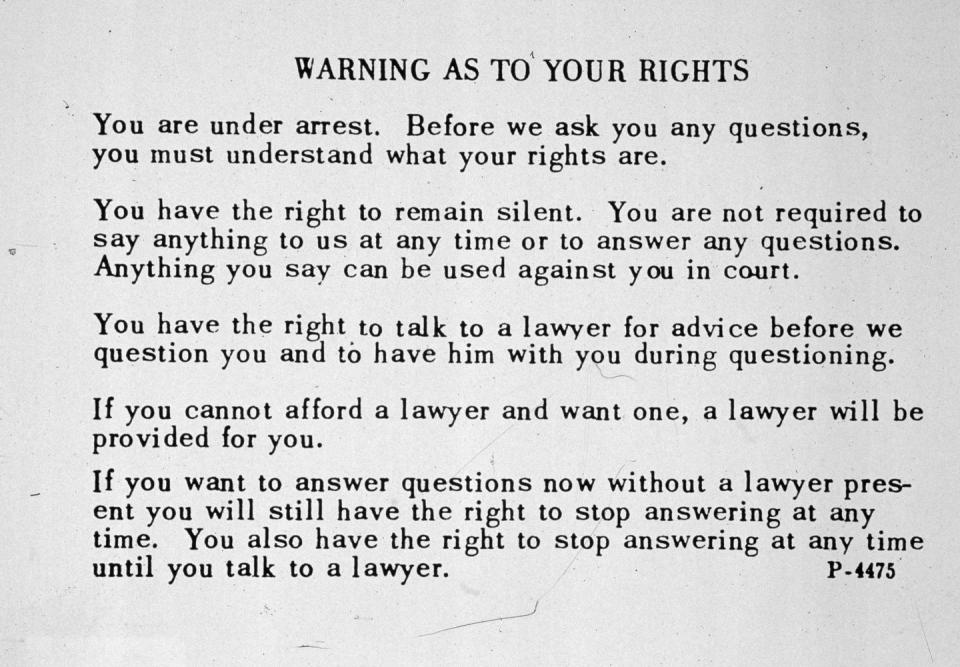

You know the script: “You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. . . .” That language, which amounts to federalized protection against self-incrimination, isn’t just the well-worn words of every cop show; it may damn well be the heart of our criminal-justice system. For that system always-ever begins with someone interacting with an officer of the law, and that interaction always-ever includes questions. What makes Miranda so crucial is that, among the slew of protections granted by the Bill of Rights, the right to not self-incriminate is a snowflake, because the very fact of an arrest puts a person at a disadvantage to the state, not to mention the immense tension that attends Johnny Law scheming to make someone forget or forfeit their constitutional right.

Go ahead—name another right that cops try to talk someone out of on the regular.

Since the 1966 Warren Court decision (Miranda v. Arizona) that made the Miranda warning law, the Supreme Court has called it a “constitutional decision” and characterized the warning as a “constitutional rule.” However, over the summer—you might’ve missed it, for the warranted public outcry over the nullification of federally protected abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson—the high court reversed those almost six decades of precedent in its ruling in Vega v. Tekoh.

The case dates to 2014, when a nursing aide named Terence Tekoh was accused of sexual assault by a patient in the hospital where he worked. The investigating officer, Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy Carlos Vega, interrogated Tekoh in a cramped, windowless hospital room and, without first Mirandizing Tekoh, barred him from leaving, ignored his pleas for a lawyer, and even threatened the man with deportation—tactics that coerced a false letter of apology. While Vega denied the heavy-handed interrogation methods under oath, he did admit to not informing Tekoh of his rights.

Tekoh was arrested and charged with unlawful sexual penetration. His initial trial ended in a mistrial and his second in an acquittal. A crucial point: In both, the government introduced the un-Mirandized statements that Tekoh had given under duress at his job. Post his acquittal, Tekoh filed a federal suit against Vega, arguing a violation of Section 1983, which allows civil-rights suits against state and local officials responsible for the “deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution.” The U. S. Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Tekoh, but the Supreme Court reversed that decision by a vote of six to three, in effect negating the position that Miranda is part of the Fifth Amendment.

Per the new ruling, officers who fail to issue Miranda warnings can’t be sued for violating the Constitution.

Be clear, taking away the reminder of this particular right is tantamount to taking away the right itself. That this usurping occurred in a sociopolitical climate of broad legitimate distrust of law enforcement makes it even more flagrant jurisprudence. Bear in mind the government audits, research, and news reporting that confirm the persistence of white supremacists in law enforcement. Bear in mind the common opacity surrounding the handling of police misconduct. Bear in mind the reasonable arguments for police abolition or, in the least, reform.

The Warren Court is oft touted as the most liberal Supreme Court in U. S. history. You’d be hard-pressed to convince me that this Roberts Court and the win-and-rule-by-any-means Republicans aren’t intent on returning us to the MAGA (is it me or is there a link between the weakening of Miranda protections and Republican efforts to exclude people with felony records from voting?) anachronistic injustices of the civil-rights era. That this decision isn’t part of the Republican will to usurp the rights of the disempowered and the freedoms of Americans who live outside the favored intersection of whiteness, maleness, and straightness.

This article appeared in the Oct/Nov issue of Esquire. Want to read every every Esquire story ever published? Subscribe here.

In his majority opinion, Samuel Alito argued that Miranda was not a constitutional right but “a set of prophylactic rules” imposed on law enforcement. While different courts have disagreed on whether to interpret Miranda as part of the Fifth Amendment, what’s fact is that my people were in bondage when they passed the damn amendment in the first place. What’s fact is that the first Bostonian police force was 47 years away when the Bill of Rights was ratified, but the slave patrols that preceded it were almost 90 years into terrorizing us. Which is also to say it’s a safe bet that the founders didn’t foresee an America where white cops with guns would bully or dupe (free) Black suspects into blabbing outside the protection of the law, making false confessions, or even snitching; a nation where thousands of innocent people would languish behind bars.

Hell, we weren’t even full humans yet.

Hence Miranda, whether constitutional or prophylactic: e-s-s-e-n-t-i-a-l.

And for anybody thinking, What’s the big deal as long as you’re not a criminal?

May I ask just who you deem a criminal? May I ask if that judgment has shifted, given, say, the widespread legalization of weed or, in the case of my home state of Oregon, the sanctioning of small amounts of hard drugs?

Maybe selling dope was never an attractive, quotidian option for you. Maybe you’ll never end up in an interrogation room with the specter of a decade-or-more prison sentence menacing your future. Maybe broken windows in your neighborhood had nothing to do with policing, meant no more than the uh-oh result of an errant baseball thrown by the kid across the street. Perhaps you seldom if ever fit the descriptions at the heart of racial profiling or stop-and-frisk policies, aren’t someone who’d get excluded from a jury or who’s too often the victim of excessive force or extralegal police killings. Perhaps the weakening of Miranda is no big old whoop-de-do to you because the box you check on the census safeguards you from overrepresentation in the world’s largest prison population and the preponderance of death-penalty convictions; because you were never the tacit target of the war on drugs or tough-on-crime bluster; because noway nohow on God’s earth would anyone have dared stigmatize you as a superpredator.

And if so, lucky privileged you. But what about protecting the vulnerable rest of us from, in a moment of confusion and dread, being schemed right out of our right to remain silent by a cop with a gun who, for any number of suspicious motives, is intent on making us talk?

You Might Also Like