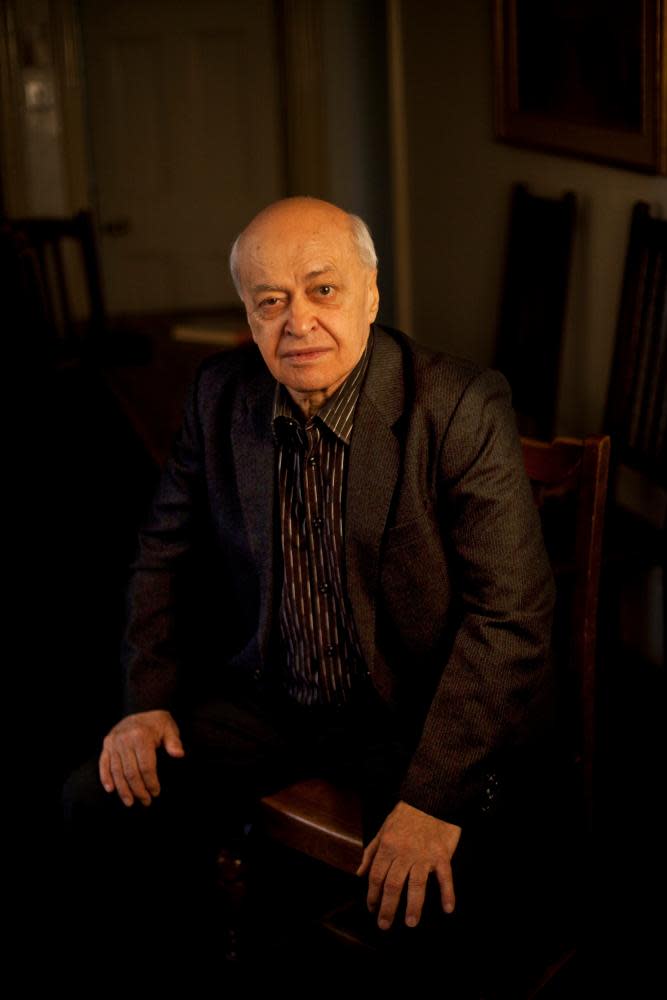

Stephen Vizinczey obituary

The Hungarian-Canadian novelist and critic Stephen Vizinczey, who has died aged 88, was a distinguished member of the diaspora that fled Hungary after the revolution of 1956. As the author of In Praise of Older Women (1965), he also belonged to the select band of writers who invent a book title that becomes familiar to millions who will never read the book.

His life and work were informed by his first two and a half decades in Hungary, which left him fearless and ready to take on all comers. After a stint in Canada, where he married and took citizenship, he arrived in London in 1966, and his flat in Earl’s Court became a dug-out from which he overlooked the cultural battlefield of the world. When no publisher would touch them, he published his first and third novels himself. All his life he spoke English with the heaviest of accents, but wrote it with unfailing elegance, clarity and wit. He was an outstanding, and frequently contentious, book reviewer.

Born in Káloz, a small town between Lake Balaton and Budapest, he was the son of István Vizinczei and Erzsebet (nee Mohos). His father, a local schoolmaster, was stabbed in the back and killed by a young Nazi when Stephen was two, and Erzsebet, a housewife and later an office worker in Székesfehérvár, the old capital, held the family together through the long nightmare that overwhelmed Hungary in the later stages of the second world war.

The widow and her clever son were as close as siblings. After an adventurous escape to the American army in Salzburg – adventures providing much picaresque material for In Praise – he joined his mother in Budapest in 1946.

As a teenager, he was enrolled as the only undergraduate member of George Lukacs’s Institute of Aesthetic Studies at the University of Budapest, and became stage-struck by the brilliance of Hungarian theatre in the early communist years. Joining the Academy of Theatre and Film Arts, he wrote two plays – The Last Word and Mama – both of which were banned. On 22 October 1956 he was among those audience members who went straight from a fevered, immersive performance of Richard III in the city’s National theatre and out on to the streets. He was on the run, ducking death, for three weeks. Characteristically, he used his stolen Russian machine gun to save a harmless cultural puppet of the regime – the Stalin prizewinning head of the Arts Academy – from a student lynch mob on the grounds that it would have been a pointless death. The man later saved Erzsebet from transportation to an internment camp.

Vizinczey escaped into Austria by the skin of his teeth. After a short stay in Italy, he made for Canada, which offered a warm welcome for Hungarian refugees. He had no more than 50 words of English and no money, but gradually picked up the language and found backers for a new magazine in Montreal, Exchange, featuring unpublished Canadian writers, among them the young Leonard Cohen. When Exchange folded, he moved to Toronto, where he met, and fell in love with Gloria Harron, a programme organiser with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. They married in 1963.

This was the key move of his life. A literature and languages graduate with a radiant smile, Gloria was a warm and witty woman who was his lifelong guide into the English language. Without her he would probably have published even less than he did. After her death last year, he wrote: “She was my editor, critic and researcher. If you have read my reviews and essays and were stunned by the depth of knowledge and erudition, the credit should go to Gloria.”

They arrived in London to promote his first novel in 1966. An erotic Bildungsroman set in Hungary and Austria between 1935 and 1956, with a teenage hero who seduces (and is seduced by) a stream of mature women, In Praise of Older Women also draws vivid sketches of Hungarian family, country and metropolitan life under German and Soviet occupation. Huge summer family feasts beside Balaton; nocturnal sex on Margaret’s Island; the defiant normality of daytime flirtation in the Ottoman steam baths as people were being snatched from their homes at night. It became a key book of the 60s, a bestseller in France, and a Penguin Modern Classic in 2010. It was filmed in 1978 and 1997, neither time successfully.

Vizinczey produced two more novels over the next half-century, meticulously working to make them as perfect as possible, writing and rewriting over five decades. An Innocent Millionaire (1983) plays exuberantly with the 19th-century conventions of provincial hero, missing treasure, dumb greed and true love. It is probably his best novel: consistently funny, ferocious and surprising. His third novel absorbed him for at least 20 years, assuming many forms and at least three titles before emerging finally as If Only in 2016. The ferocity against ruthless idiots remained undimmed. No one wrote more keenly about the mean abuse of power or the cruelty of the rich. To these are here added fantastical elements in the spirit of Swift and Mark Twain.

He wrote regularly for the Times in the late 60s and early 70s, and later for the Sunday Telegraph. These reviews and essays are gathered in two collections that will be read as long as the novels. The Rules of Chaos (1969) and Truth and Lies in Literature (1986) are both timeless and very much of their time. His demolition of William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner and praise of Senator Eugene McCarthy are frontline reports from 1968. His expansive Times Saturday Review pieces on Stendhal and Heinrich von Kleist are classics still fit to convert English readers from polite respect for those giants to love and understanding. He could do steely, analytical reporting, too. His 1983 Telegraph piece on the men who fought the mafia and died doing it is a lightning flash on a terrible moment in modern Sicily.

His belief in “the wickedness of human beings” led him always to examine the powerful with mistrust. Sadly, and to the despair of his family, friends and many admirers, Vizinczey had a taste for litigation, and a genius for shooting himself in the foot. At one point he seemed to have quarrelled with virtually every publisher and agent in London and New York. In 1965 he turned down Abby Mann, the Oscar-winning writer of Judgment at Nuremberg, for the screenplay of In Praise.

The past brought consolation. Vizinczey measured all modern writing – and his own – against what he called “The Company of the Dead”, who never failed to inspire him. In addition to Stendhal and Kleist, it would be impossible to exaggerate the importance he gave to Pushkin, Balzac, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Twain, all of whom he read and reread all his life.

He spent his last years revisiting the Company, watching French films of the 50s, keeping watch over the slowly failing Gloria and blogging with new, young readers about the masterpieces he never tired of: King Lear, The Idiot, Candide. Above all, he never ceased to grieve over what he saw as the infantilisation and hypersensitivity of the modern world.

He is survived by his daughter, Marianne, his stepdaughter, Mary, and two granddaughters, Monica and Josephine.

• Stephen (István) Vizinczey, author and critic, born 12 May 1933, died 18 August 2021