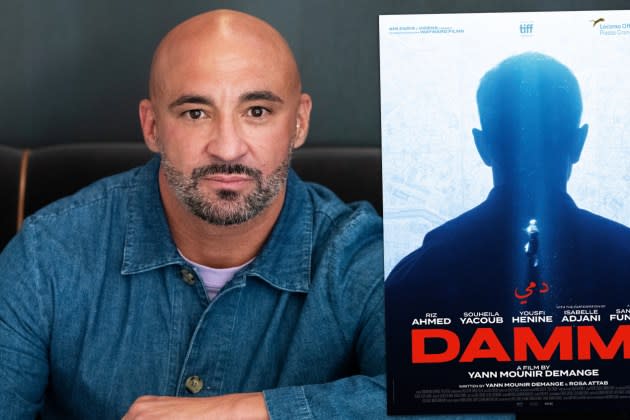

How New Short Film ‘Dammi’ Eased Pain, Shame & Tribal Search For ‘Blade’ Director Yann Demange

Of all the films that played at the recent Toronto Film Festival, a short called Dammi might have the biggest impact in unlocking a filmmaker to do his greatest work.

Yann Demange had his breakout on feature his debut on ’71, then made White Boy Rick, and when the strike ends he’ll revive for Marvel the Blade franchise with Mahershala Ali. Turns out it’s not a coincidence that he was drawn to those films about outsiders trying to find a place to belong. That is what Demange has addressed directly with Dammi, after years of feeling guilt and shame for being raised in foster homes and not getting the chance to embrace his roots as an Algerian and Muslim.

More from Deadline

Locarno Opening Night: Riz Ahmed’s Impassioned Message & How The Strikes Are Impacting The Festival

Meet The WME Agent Helping Drive The Success Of A Wave Of British Politics Podcasts

In Dammi, Demange directs his close friend Riz Ahmed in a role that is essentially the filmmaker, down to carrying his real name, Mounir. The haunted young man comes to Paris circling the drain because he has never been able to find his own tribe, or come to terms with his estranged Algerian father. He quickly connects with an Algerian woman named Hafzia (Dune: Part Two‘s Souhelia Yacoub). He marvels at how comfortable in her skin she is, as a person of Algerian descent who is also a Parisian. It is clear that she is his path to a tribal reckoning, and a life with someone he has connected with. But he finds himself unable to commit, and is often seen underwater in surreal scenes as he drowns in this tangle of emotions and remains unable to even speak or really be seen by his estranged father.

To say this crosses into biographical territory is an understatement. Demange has never been able to express his feelings to his father, but managed to do so here, through Ahmed. The short is surreal storytelling, but Demange cast his real father, Yousfi Henine, and so his best friend carries on conversations that Demange never was able to because his father was never talkative and Demange too insecure to press him. It created an existential hole in the director, one he finally filled with a short that hopefully will get a wide release because it will connect with many people, men in particular, who grew up with toxic masculinity traditions that regarded showing emotion to be weakness.

And to think, Demange initially approached this short film as a “palette cleanser” between features, one that would lightly touch on personal themes. But Rosa Attab, part of the company Vixens that was a producer, had other ideas. “Rosa knew me, my background, she knew about my father, and foster care,” Demange said. “She’s an Algerian woman and said, look, I hope you don’t mind, but I took the liberty of writing a voiceover. It’s not the voiceover in the film, I rewrote it, but it put me in the heart of the film, where I had no intention of being. I finally said, ‘Oh, fu*k it. We were at a similar stage in life and started to talk a lot about this sense of not really feeling like you belonged anywhere, this feeling of shame and how toxic shame can be, and how you need to try and transcend those issues in order to be able to make deeper interpersonal connections. Rosa pushed me to make a more personal film.”

When I ask him to explain the same, Demange shared with me an essay he wrote, called The Long Answer, which was published in a collection called The Good Immigrant. It explains much. Demange doesn’t like to talk about it, not wanting to embarrass his father or mother, both of whom are still alive. He wrote that he’s mixed race, with a French white mother and an Algerian father. He grew up for a time in London, where he was called a ‘Paki’ by bullies in school, getting into many a fight over it. He held a French passport, though he hadn’t lived there since age 2. His mother was Catholic living in London, his father a Muslim living in Paris. “My parents left my identity for me to figure out,” he wrote. “Neither claimed me for their tribe. So at a very early age, one thing became clear to me. I’d always be an outsider.”

Not that he didn’t try. He has mixed race brothers, one Afro-Caribbean, the other Argentinian and half Indigenous. While he ended up being fostered between ages four and 12 and that confused his tribal issues even more, he later got to meet his half brothers and envied their ability to connect with their ethnicity. His oldest brother embraced his Black skin color when he moved to New York in the late ’80s. When he returned wearing Spike Lee merchandise and reading Black literature, Demange devoted himself to a love for NWA and its seminal Straight Outta Compton album, and his brother had to explain why it was not appropriate for him to wear the ‘BlackMan” T-shirt his brother brought home, a play on words for Tim Burton’s Batman film that was all the rage. When his other brother embraced his indigenous South American roots and got a Native American’s head tattooed on his chest, Demange did the same when he was 15. His older brother laughed his head off: “You are not part Indigenous, bro!” Seriously, what the fu*k was I doing? Cultural appropriation, I believe they call it. On top of it all, it was a fu*king shit tattoo, done by a shit artist. The amount of comments I’ve had from North Africans who have seen that tattoo…,” he wrote.

Demange gravitated toward film when he visited Algiers for the first time in 1991 and met relatives he did not know he had. They embraced him, and the film path was lit by The Battle of Algiers. Beyond being a point of pride for Algerians, the film was important for Demange because it turned out his aunt was one of the stars, in her one and only screen role. She played the beautiful woman who plants a bomb in a milk bag. When he returned to London, a return trip to Algeria to see family became impossible with the eruption of a civil war that claimed 250,000 lives and made a return too dangerous.

Demange ‘s name became known in London directing circles for his work on Top Boy, a big hit series in London. He wanted to do a feature set in Algiers, but was able to say what he wanted to in ’71, even though that was a taut drama about a British foot soldier caught on the wrong side of Belfast after the murder of another soldier. The soldier (Jack O’Connell) runs for his life, and doesn’t fit on either side of the struggle. Same with the protagonist in White Boy Rick, the only white kid left in Detroit after “white flight.”

After ’71 took off like a rocket, Demange found himself meeting in Europe with CAA agents Roeg Sutherland and Maha Dakhil. They told him a major career awaited him in Hollywood. When he told them he was broke, Sutherland offered his couch, and Demange stayed there a good half year until he got work. It will be Sutherland who is tasked with making sure Dammi gets seen by the widest possible audience, a challenge for a short film.

When I met Demange, he had just gotten to Toronto. His luggage was lost, and he knew that the chance for exposure on Dammi was dampened because his friend and star Riz Ahmed stayed home, to stand in solidarity with his fellow striking SAG-AFTRA members. But he also acknowledged he had won a victory, just by facing his shame, his rootlessness, and because he opened channels with his father, even if that communication was accomplished through his screen alter ego.

“The short form was the best for me,” Demange said. “I didn’t want to go through the process of trying to get a feature version made and people not understanding it. You have to try and make it adhere to conventions for it to be accessible. This gave me freedom and I felt very vulnerable making this. It was the most exposing that it is actually my father in the film. That’s my dad. It’s funny, we never really hugged or fought, but he’s a very old school man, and we don’t talk. Making this film got me the closest I’ve ever been to him, even though it’s Riz having these conversations, and moments with him that I’ve never had. But it was like we had them through him. It was like a strange therapy.”

A strange therapy with a breakthrough.

“At the screening, he was quite taken aback,” Demange said. “He was speechless. By the time I’d seen him, he’d cried. We’ve never been able to talk. I was in foster care for a long time. I don’t call him dad. I didn’t know I had another brother until I was 13. From his side, we were estranged and got to know each other later in life, and I was trying to make sense of my heritage and get to know my Algerian side more. But when you saw the film, it was the first time he felt like I spoke to him, and he understood. Emotionally, it was a very charged moment.”

Only while making Dammi did he realize he was indirectly working out in earlier films his tribal issues and the sense of shame and rootlessness. Blade, for instance, is a singular hybrid, born with both human and vampire blood in him. That allows him to appear in daylight, and he becomes an accomplished crusher of bloodsuckers, fighting off the vampire urges that creep up inside him, but unable to be part of either tribe. There is every reason to imagine now he’s dealt with issues that brought him shame him, Demange can use those lessons, and focus on directing the two-time Oscar winner Ali in a ferocious new Blade, a tall order because of the indelible link to Wesley Snipes in those early New Line R-rated films.

“They gave me the R, which is so important,” Demange said. Where as Demange once said that his personal turmoil gave him an outsider’s perspective that was helpful, he feels more at peace now, having faced his demons in the film he made.

“I come out of this wanting to be more open, more vulnerable and bring a more personal aspect to my work,” he said. “But for Blade, we are going to have fun because Mahershala is such a deep actor. I’m excited to show a kind of ruthlessness, a roughness he has, that allows him to walk the earth in a particular way. I love him for that. He’s got a dignity and integrity, but there is a ferocity there that he usually keeps under the surface. I want to unleash that and put it on the screen.”

Best of Deadline

SAG-AFTRA Interim Agreements: Full List Of Movies And TV Series

The Highest Grossing Movies At The Box Office Every Year Since 1989

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.