I Prayed For Years That No One Would Discover The Issue With My Private Parts. Now I'm Done Hiding.

The doctor held my penis in his right hand for my parents to see. I was 7 and lying on the examination table at my pediatrician’s office.

“If you come closer, you can see that one of the testicles is not in the scrotum,” Dr. R said.

My right testicle was the focus. It had made a home within my groin.

“In the womb, the testicles are not yet in the scrotum until the 32nd week,” the doctor said. “But occasionally a child is born with one or both testicles undescended.”

It was the early ’80s. Dr. R spoke like he and I were the stars of an after-school special designed to educate Americans on the life cycle of testicles.

I wanted to scream. I wanted to run away. I wanted to be anywhere but that office.

Before puberty, he explained, a testicle can sometimes ascend back into the groin spontaneously. Or it can end up there as a result of force. The word “force” immediately brought to mind a street hockey game from months earlier. One of the bigger kids, Paul, hit a slap shot that landed in my nuts.

I could kill Paul.

“Then,” the doctor warned, “if we cannot push the testicle down before it grows bigger during puberty, surgery will be necessary.”

His words sent waves of terror crashing along every shore of my body. Tears streamed down my face.

***

The name for this condition, when originating at birth, is cryptorchidism. It derives from the Greek words kryptos and orchis, meaning “hidden” and “testicle.” Data suggests that 2% to 8% of newborns experience it. Most of the time, the condition involves one undescended testicle in the inguinal canal, the little highway that runs from the abdomen to one’s private area.

When it occurs after birth, as the condition probably did with me, it’s described as an “ascending testicle” or an “acquired undescended testicle.”

If the condition does not resolve on its own, and the doctor cannot guide the testicle back to the scrotum by hand, surgery called orchiopexy will be performed. During the procedure, the doctor makes an incision in the groin and examines the testicle to ensure that it is healthy. An additional incision is made in the scrotum to create a “pocket.” Then, using a grasping tool, the doctor “gently pulls the undescended testicle down into the pocket.”

The surgery has a high success rate. Doctors note that it typically improves a child’s self-esteem by reducing future embarrassment.

***

After Dr. R terrified and humiliated me, he kept me on the examination table. Every part of me pushed to get up, but he held me down with his left hand placed firmly on my chest. He used his right hand to locate the outer shell of my wayward testicle.

He pushed down. The pressure made me nauseated.

“Please stop,” I said.

The doctor continued kneading my testicle like a baker manipulating dough.

“Just a little longer,” he said.

As I pushed harder to get off the table, my father helped hold me down. It was all so primitive — the hands of men and their force. The doctor continued pressing until I felt my testicle pop into my scrotum. I cried tears of relief.

I’d been fixed.

But as the doctor removed his hands from my body, the testicle popped back up like a yo-yo recoiling. I told the doctor what I’d felt. My parents trained their eyes on the wall behind me, as if averting eye contact could mask their worry.

“We can try again another time,” the doctor said.

I didn’t know what would be worse: enduring the humiliation of this procedure anew or living with the shame of my half-empty scrotum.

***

The Mayo Clinic reports that having a testicle outside the scrotum increases the risk of testicular cancer and infertility. It also means a 10 times greater risk of testicular torsion, a painful condition in which the cord bringing blood to the testicle gets twisted, cutting off flow and necessitating emergency surgery.

I learned about these health risks when I overheard Dr. R whispering to my parents. On many nights following the visit to the doctor, I stayed up late praying to God that I would be able to have kids. I prayed that I wouldn’t get cancer.

I prayed that no one else in the world would ever find out.

In middle school, we watched a video in health class showing the boys how to perform a testicular self-examination. The teacher passed around a synthetic model of a scrotum. It contained a pebble-like lump for us to discover so we’d know what a testicular tumor felt like. I held the model, imagined my future tumor and ran from the room to vomit.

Throughout my early adolescence, I’d hide sore throats from my parents to avoid visits to the doctor — his cold hands and the shame. I also developed a habit of using my left hand to periodically push my left testicle downward so as not to become The Boy With Two Missing Testicles.

Sometimes I comforted myself with the idea that my errant testicle would give me some kind of superpower: specifically, that its unusual location would lead to a larger penis in adulthood. When the absurdity of that conclusion sunk in, I resorted to more scientific but no less wishful thinking. Despite Dr. R’s words, I tried to convince myself that it was natural for the left testicle to start out life in the ball sac whereas the right one liked to take its time arriving.

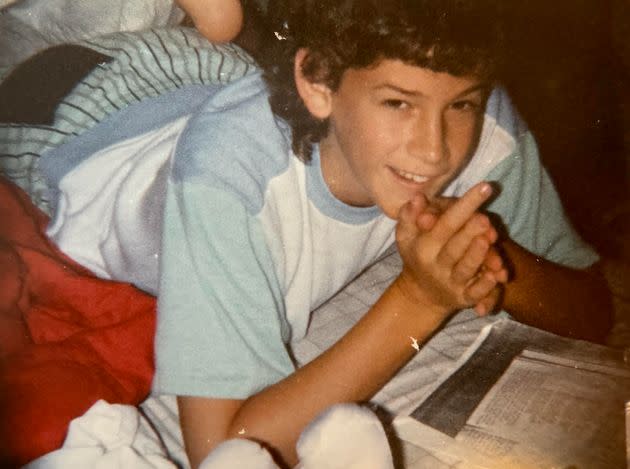

Dr. R tried a couple of more times at annual physicals to push my testicle down, when I was 9 and 10. Those tries also left me in tears. By age 13, Dr. R told me he’d make “one last try” before surgery became necessary. The appointment was scheduled for a week before my bar mitzvah. The timing felt like an ominous coincidence or the opportunity for a miracle.

I continued to practice my Torah reading for a ceremony that would mark my passage into manhood.

I prayed.

***

On the car ride to the doctor’s office for the final appointment before surgery, my father and I didn’t talk. It was a continuation of years of silence. My parents lacked the language to speak with me about what was happening. Everyone was too focused on fixing the physical aspects of my condition to notice my emotional wounds.

I kept my shame and my fear to myself.

Once in the examination room, it was another high-tech affair. This time, it involved my standing in front of the patient examination table with my pants down — my father stood in the corner because why the hell not? — while Dr. R crept up behind me like a Scooby-Doo villain. Again, he used his right hand to apply pressure on the outer rim of my right testicle. Again, it made me instantly nauseated. Again, I was crying.

But this time, with every centimeter of testicular travel, Dr. R was becoming my hero. I stood as still as a statue. I would have stood there forever if it meant avoiding an operating room. I wanted this testicle to be inside my scrotum more than anything in the world.

“There,” Dr. R said. The eagle had landed.

The testicle didn’t pop back up. It felt like it belonged there. My entire body exhaled. I could have floated to the ceiling.

One week from my bar mitzvah, I was a new man. If there were anything that could prove God’s existence, this was it.

Dr. R was thinking in less celestial terms.

“Try to avoid getting hit there,” he said.

***

Trauma is a stubborn thing. It doesn’t just disappear. It shifts shape. After Dr. R’s success in descending my testicle, I lived in fear of it happening again. During the sexual activity of my college and later years, I’d ruin moments by overreacting to a partner’s interest in exploring my genitals. My jumpiness elicited discomfort in others who lacked context for my behavior. Confiding about my childhood experience to anyone else was unthinkable — it remained a dark secret.

I avoided swimming pools after noticing that cool water pushed my right testicle upward. Doctor visits still stirred the same dread. I fixated on the slightest discomfort in my groin. An MRI in 2009 revealed a benign mass in my inguinal canal, likely from the years in which my right testicle resided there. It is the literal scar of my experience, hidden, as the condition was, from nearly everyone else.

“Time,” the saying goes, “heals all wounds.” This turns out not to be true. Sure, time can provide the chance for physical recovery, but I’ve learned that healing requires something more. It requires honesty.

In my mid-20s, I finally found the courage to share my secret with a boyfriend. One evening, while we touched, I broke through the silence I’d perfected for years.

“I had an injury down there,” I said.

“Oh,” he replied. “What kind of injury?”

I described my former condition, the long road to its eventual repair and the fear of ending up all these years later under a surgeon’s care.

“I am so sorry you had to go through that,” my boyfriend said. “I promise to be gentle.” And he was.

***

Thirty years after Dr. R’s discovery, my childhood shame and fear remain a part of me. I don’t run from the memories or try to relegate them to a place reserved for things I hope to forget. Instead, I find myself drawing from the experience.

I now understand that trauma derives a lot of its power from the shame we layer upon it. I know that one way to deprive a challenging experience of some of that power is to let others in. I know about the corrosive effects of secrecy. I had once held a different kind of secret about my sexuality from family and friends. I was fortunate to be met with affirmation each time I confided in others. But I amplified my unease for years by keeping my truth a secret.

I’m now a husband and a father of two children, an 11-year-old girl and a 2-year-old boy. I am attuned to their inner lives in ways I trace to my childhood nights. With my eldest, I’ve learned that “What’s on your mind?” is often a better question than “How are you doing?” At doctor’s appointments, I let my daughter know she can speak with the physician in private if she’d like. These are small examples of doing what I wish had been done for me.

I’m mindful of how easy it is to link our self-worth to the experience of our bodies. I’ve also absorbed the lesson that many of the experiences that shape us most can be invisible to others. We don’t always see the heavy things people are carrying. But knowing that everyone has something transforms the way one moves through the world. It nudges us toward compassion.

To be sure, I’ve gleaned lighter lessons, too. For starters, if my son plays street hockey, he will wear a cup. And despite my skepticism of a higher being, it certainly doesn’t hurt to pray.

Finally, I’ve learned that wounds can remain long after they stop hurting. Sometimes it’s the scars that help us remember what’s important.

Brad Snyder’s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in River Teeth’s Beautiful Things, Sweet Lit, Under the Gum Tree, The Gay & Lesbian Review, Blue Earth Review and elsewhere. He is pursuing his master’s in creative nonfiction writing at Bay Path University. You can find more of his work at bradmsnyder.com and on Medium.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.