How NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly Does It All…Almost

Mary Louise Kelly was in a bunk in a dusty trailer parked behind one of Saddam Hussein’s abandoned palaces, crying herself to sleep. It was 2010, and Kelly was the Pentagon correspondent for NPR. Hours earlier, as she was strapped into a Black Hawk helicopter lifting off for the trip into Baghdad, she received an urgent call from the school nurse. Her youngest son Alexander, then 4, was having trouble breathing. He had a history of respiratory infections, and the nurse was so worried that she recommended sending him to the hospital.

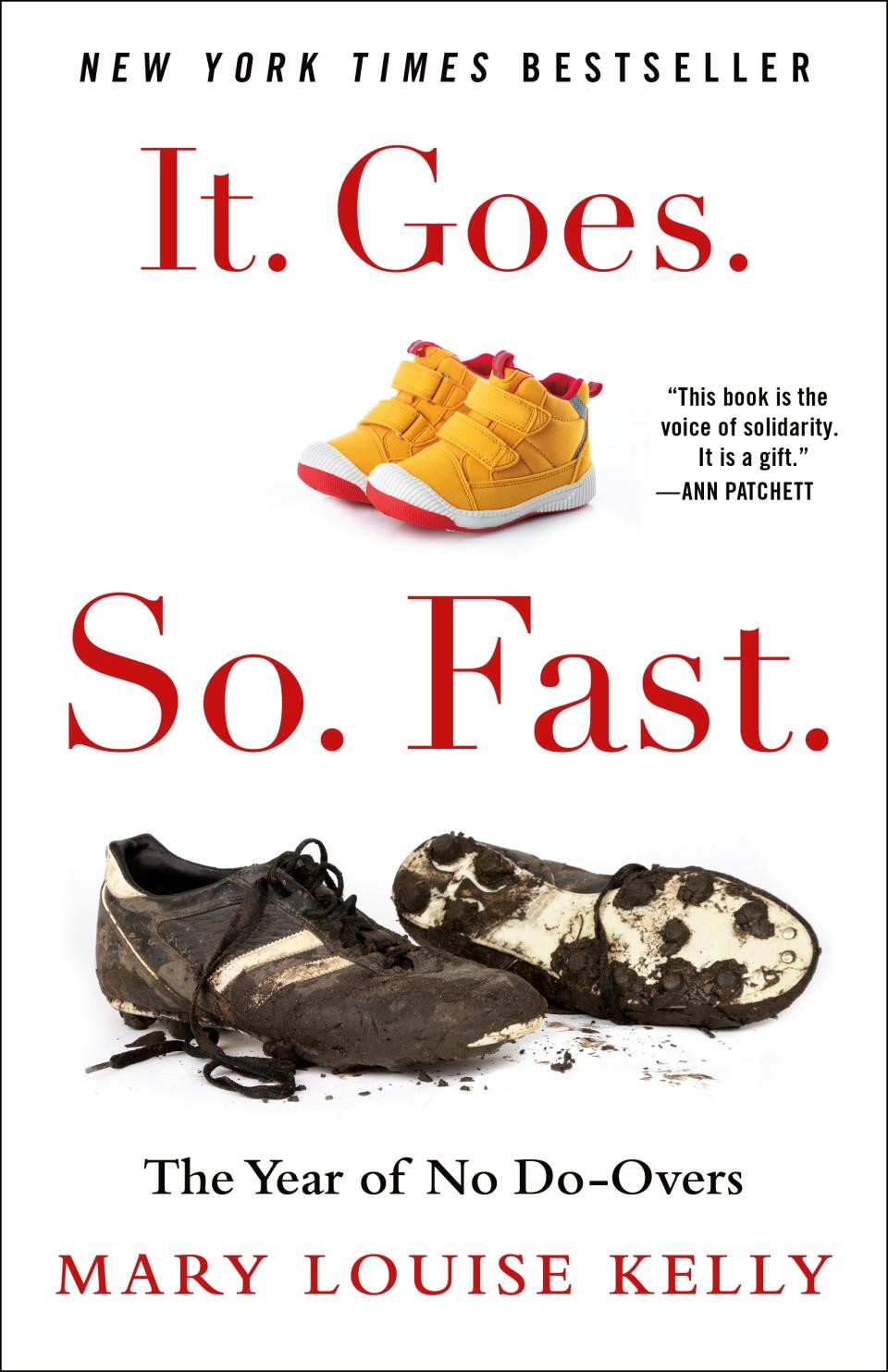

It was the moment, Kelly, 52, writes in her new memoir “It. Goes. So. Fast. – The Year of No Do-Overs” (Henry Holt and Co.) when she “hit the wall.”

More from WWD

Her son would be fine, but seven months after that phone call from the school nurse, Kelly resigned from her job at NPR. Her children needed her and sojourns to war zones just were not conducive to parenting young children, she concluded.

“Sometimes the problem isn’t the demands of our bosses but the expectations of our society,” she writes. “As one friend…put it, ‘Mothers remain the default for everything.’”

It was not the first time Kelly needed time away from her career to take care of her family. When Alexander was 2 years old and had yet to begin talking, she took a yearlong leave from NPR in order to shepherd him through intensive speech therapy. The discussion with her husband Nick, a lawyer, about who would stay home with Alexander was pretty short. “Nick made more money than I did,” she writes. “Giving up his paycheck would involve more radical lifestyle changes than giving up mine.”

All relationships require compromise. Women still tend to make more of them than men. But Kelly’s book is not a screed about the stubborn staying power of the patriarchy. Rather, it is one woman’s exploration of choices made, of the eternal balancing act undertaken with joy and just a few regrets.

When she quit her job at NPR shortly after that miserable night in Baghdad, she decided to write a spy novel, culled from her many years on the national security beat. As a novelist, she could set her own hours. She named the female protagonist Alexandra James, a reporter, after her sons Alexander and James. Her first book, “Anonymous Sources,” was published in 2013; a second one, “The Bullet,” bowed in 2015.

Three years later, she was ready to go back to working full-time. She returned to NPR as national security correspondent (and guest host of “Morning Edition” and “All Things Considered”) in January 2016, right after the Paris terrorist attacks and in the midst of the “Trump cyclone.” By then her kids were older, 10 and 12. In 2018, she took over as anchor of “All Things Considered,” which reaches 10.5 million listeners every week.

When she set out to write “It. Goes. So. Fast.” during her eldest son’s senior year of high school, her goal was to document a year in the life of a working mom who was finally going to be present for the soccer games. It was her last chance before her son James went off to college and there were no more soccer games. She took several weeks of book leave. She made some games, and missed others. She suffered heartbreaks: in 2021, she lost her father, who had battled cancer for many years; her husband asked to separate.

Kelly bookends “It. Goes. By. So. Fast.” with the aforementioned Baghdad trip and a January 2022 trip to Ukraine, when Russian President Vladimir Putin was amassing troops on the country’s eastern border. By mid-March, during the early weeks of the invasion, NPR, and every other news organization, was sending teams of journalists to Lviv. And Kelly’s editor asked her if she wanted to go back to Ukraine. She very much did, she writes. Reporting from the field is where she feels the least conflicted, she has one job — to focus on the story at hand, not the 15 stories in a typical installment of “All Things Considered,” not the inevitable home front obligations.

“It’s the only time where I feel something approaching zero guilt.”

But…she does not go to Ukraine, not this time. “If I say yes to this assignment, I will miss a significant portion of what is left of James’ senior year,” she writes. “When the job and kids collide, the kids come first.”

Here, Kelly talks to WWD about the story that got away, the recent layoffs that rocked the NPR newsroom and the one indispensable life skill she has mastered.

WWD: Would you call this book a memoir?

Mary Louise Kelly: The threads of my life and anyone’s life are messy, complicated. I found it impossible to write about being a mom without bringing in being a journalist and vice versa. So I think it ended up being a memoir. But it started out as me just trying to chronicle a year in real time as it was unfolding, which brought its own terrors because you never know. What if nothing interesting happens from April onward and it’s an anticlimactic book?

WWD: Your previous books were spy novels. Did you have any trepidation about exploring personal struggles, making yourself the story and the exposure that could bring to yourself and your family?

M.L.K.: Oh, sure. Absolutely. It gave me pause to think about putting myself out there in this way. I have always written essays and pieces that touched on things happening in my life and my own experiences, but this is a new level. And it did give me pause. As far as my kids went, I had them read every chapter in which they feature prominently. They had veto power. They helped me fact-check.

WWD: Did they veto anything?

M.L.K.: They didn’t. They did say things like, “that’s not how I remember it, I think it happened this way.” And sometimes they helped me get things right. My goal was that this would be very much my story about my dilemmas and my choices, and how I’m trying to wrestle all this. And I suppose what gave me courage was in my day job as a reporter and an interviewer, I am regularly asking people very personal questions, and often on what is the worst day of their life. Because that’s when they’re in the news, the day that a hurricane came and blew their house down, or an armed gunman showed up at their kid’s school, or they were trying to get to work in New York and a plane flew into the World Trade Center. I’m asking people to talk to me and take really hard questions. Hopefully in a respectful way. But that’s my job; to bear witness and share with the rest of the world and our audience what is happening and what the stakes are and why we need to care. And at a certain point, I thought, well, why should I be exempt from the questions? And this is what I’m wrestling with right now, so let me turn the lens on me.

WWD: Well, speaking of personal questions, in the final chapters you write, quite briefly, about your shock when your husband asks to separate. So how are things now?

M.L.K.: I’ll thank you for that question. Since I finished writing this last summer, my husband and I have divorced. And I think I’ll leave it there, other than to say that I’m really proud of everything we’ve built over 25 years of marriage. And, as I hope it comes across in the book, he is a wonderful, wonderful dad. I wish him much happiness on his next chapter.

WWD: And how has it been for you being a single person at this point in your life, which I gather you did not expect?

M.L.K.: Again, thank you for the question. I think I would answer that by saying female friendships have been the central relationships in my life. Before stepping into this interview, I was swapping texts with some of the women mentioned in this book; one of my closest friends is starting a new job today and so we were making sure the flowers we’re sending her are waiting for her at the door when she gets home tonight. Little gestures like that — which I have been on the receiving end of throughout all these years, but particularly during a year that was full of challenges and inflection points for me — has meant the world and has made me stop and pause and be very intentional in nourishing [those relationships].

WWD: The pandemic was hard on everybody, but it was particularly hard on moms and especially moms of limited means. It really crystallized what you write about in this book, that moms remain the default for everything. Do you think enough has changed in corporate culture to support working mothers?

M.L.K.: It’s such an eternal question, isn’t it? I mean, on the one hand, you could look at what women make to the dollar; every spring [on Equal Pay Day, which this year was March 14], women catch up to what men made last year in the same job. How that persists in 2023 is absolutely beyond me. But I do see changes on a larger level. Things like parental leave, where the U.S. is still a laggard compared to the rest of the world. When I had my [children], I was working at NPR, and we were given one week [of paid leave]. You could accumulate sick leave. But I wasn’t sick. I was recovering and trying to learn to nurse and trying to sleep and doing all the rest. I ended up taking six months, most of it largely unpaid, with each child. NPR has changed that policy; regardless of gender, it’s three months.

When my kids were small, I was so scared to ask for [time off]. I didn’t want to be seen as mommy tracking, as not being fully available and completely committed and as ambitious as I ever was. If I needed to take my kids to the doctor, I would say, “I’m going to be late because there’s a doctor’s appointment that I need to be at,” not mentioning my kid. As I’ve gotten older and moved into more senior roles, I’ve seen how important it is for me to role model. You bring all of yourself to this job. And of course, you’re going to have things where your kids need you and it conflicts with your day job. And I need to be very publicly modeling that this is doable.

Now I go out of my way when it’s the parent-teacher conference, or the kids’ orthodontist appointment, to mark on my calendar, where my whole team can see it: MLK out of office and here’s why. Why should I hide that? It is part of who I am and what I bring to my work. This is how we keep new parents in the workforce, by showing that it is possible to do both. We can all do our jobs from home and on Zoom and on our cell phones, and that’s great. But if I’m going to be reachable 24/7, I also need to carve out the time that I need to protect and take care of my family. And I’ve been very, very upfront and public about doing that in recent years.

WWD: How is the mood at NPR in the wake of the layoffs?

M.L.K.: Thanks for the question. I’ll just state the obvious, which is, I speak for myself, not for NPR, the organization. It’s been really tough to know layoffs were coming but not know exactly what show or what people would be affected. This has been a really difficult couple weeks in the newsroom. I will also say that the kindness and generosity and solidarity that I’ve witnessed from colleagues has truly been incredible. For us on “All Things Considered,” taking the day off to process news isn’t [an option]. We’ve got a show to get on the air every day, including today as I’m speaking to you. And that has, to me — and I’ll speak only for me — been helpful at a time when we are losing incredibly talented colleagues, to be reminded that this is the mission and like any other day, we’ve got to get on with it. I think people are both processing what’s happened and also thinking, OK, meanwhile, how do we fill this four minutes of empty air and what are we going to do about this story? And who are we reaching out to try to answer this question? And here we go.

WWD: Every journalist I know has a story that got away. What’s yours?

M.L.K.: I have regrets about choices I made. And it does cut both ways. For years on the national security beat I covered Russia. But in the middle of the [Robert] Mueller investigation into [President Donald] Trump, I put in an interview request for the head of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service. It’s called the SVR, and it’s Russia’s answer to the CIA and they never talk on the record and they really don’t talk to Western journalists. But I kept pushing and I have no idea why but one day the answer came back and it was yes, we’ll talk to you. It became this incredible hustle to try to figure out how to get me and a producer on a plane. And then they [the Russians] changed the date that we had set [for the interview]. And the new date was in the middle of a long family vacation that had quite complicated logistics, where I couldn’t just show up two days later. I was thinking, I can’t possibly not do this interview and I can’t possibly miss this family vacation. And then I reminded myself what I have always said: when the kids and the job come into conflict, the kids have to come first. And so I turned down the interview, and we undid all the plans. And I have asked ever since for an interview, they’ve never said yes again.

WWD: You have taken breaks from your day job to write books. Do you see yourself doing that again? And how long do you see yourself at NPR?

M.L.K.: I’m fully all in and committed and at a lovely point in my job at NPR where I still feel challenged, and a little terrified every day. It’s hard not to be when a mic light goes on and you are live and you know there’s a few million people listening. I hope I never lose that slight nervousness. But I also am at a point where I know what I’m doing. And I enjoy doing it. And I’m good at it. I would have been scared to say that out loud 10 years ago. But now I’m like, you know what, I’m good at what I do.

This gives meaning to my life. And feels like meaningful work and NPR remains a place where I can do that meaningful work. I do love writing books, it’s just a totally different challenge. My day job is creating a two-hour radio show every day, which is great. But you know, the next week it feels like ancient history versus a book that’s going to sit there on my coffee table — for better or worse — for forever. I bookend the book by talking about my life as a play. And I’m staring down act three and I don’t quite know what it will hold. I’m a little nervous that [it won’t] be as exciting as what came before. Are the most crazy, joyful, adventures behind me? What is the next 20 years going to look like? But I do think I have another act.

WWD: Whatever you decide to do, you have a very important skill than I am not sure can be learned or taught. You seem to be able to sleep on 11-hour plane flights and 15-hour train rides.

M.L.K.: Being able to sleep in strange places is an underrated life skill. Working on “Morning Edition” helps. When you are getting up to report to work at 3:30 in the morning, day after day, you reach a state of sleep deprivation where if you sit down in a chair, you’re out.

Best of WWD