Murdered, tortured or in hiding from the Taliban: The special forces abandoned by Britain

It was around 9am when Ahmad was discovered, crumpled and bloodied, in a dried-up canal. The Afghan former sergeant had been left for dead by his Taliban attackers who had used the butts of their guns to strike his head until he was barely recognisable. His 13 years of work with the British special forces had made him a prime target.

All he can remember is being ordered to hand over 20 rifles he didn’t have – and then the savage blows began. “One of them said ‘He has nothing to give us,’ and said they should kill me. They beat me so badly. Four of my teeth got knocked out and my nose was broken. I had to go through many surgeries.”

Ahmad, whose name has been changed to protect his safety, is one of hundreds of Afghans who served in two little-known elite special forces units known as the “Triples” –which were set up, trained and funded by the British – and yet have been denied relocation to safety in the UK. Most that we’ve spoken to, including Ahmad, have been told by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) that they are not eligible because they did not work closely or in partnership with the British.

Instead, they have been left to the mercy of the Taliban, who are hunting them down to exact information and weapons and to inflict revenge – including murder – for their service.

A six-month-long investigation by The Independent, in collaboration with investigative newsroom Lighthouse Reports and Sky News, has found that dozens of these former commandos have been beaten, tortured or killed by the Taliban since August 2021. We have verified 24 such cases, including that of a man who was shot in the head as he went to buy groceries, killing him instantly, and another who was tortured so severely that his family said it would have been a greater mercy if he had been murdered.

Others have been forced into a life of destitution, unable to find work because they have to move location every month to escape the Taliban. One former soldier described his new life, trying to find pieces of discarded metal to sell in order to buy food for his family. Most are living separated from their wives and children, with occasional rendezvous happening under the cover of darkness.

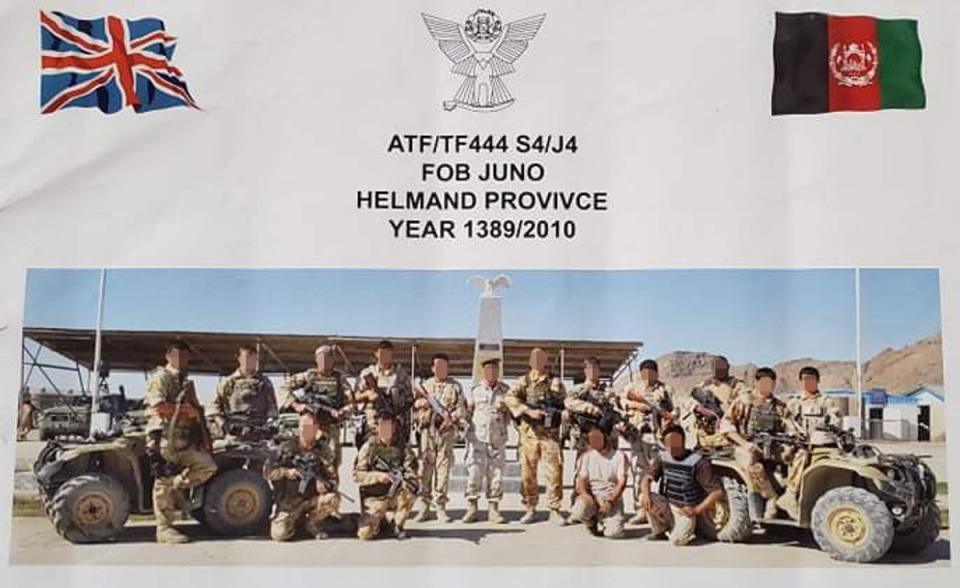

After speaking to more than 100 Afghan former members of the two Triples units – officially called Commando Force 333 (CF333) and Afghan Territorial Force 444 (ATF444) – and a number of British military veterans who served alongside them, as well as analysing reams of documents, we can also reveal that the MoD’s claim that members of the Triples did not serve closely with the British is wrong. In fact, they served in such close partnership that members received a salary directly from the UK government, with many of them paid British money until days before the fall of Kabul.

One 2012 certificate given to a Triples mechanic referred to him as a “valuable, reliable and hardworking employee of the British and Afghan forces”. The MoD rejected his application for help in June. Members of the 333s have also provided ID cards that bear only the British flag and state clearly that “the bearer of this pass ... is partnered with the British armed forces”.

Major General Charlie Herbert, who worked alongside the Triples and was a senior Nato adviser in Afghanistan between 2017 and 2018, said: “I can think of no other Afghan security forces who were more closely aligned to the UK than 333 and 444, nor who more loyally or bravely supported our military objectives. That any of them remain in Afghanistan more than two years after the evacuation is abhorrent.”

The MoD’s failure to help these Afghans, who are documented as having served shoulder-to-shoulder with UK Special Forces (UKSF), is thought to be in breach of the department’s own Afghan relocations and assistance policy (Arap), the scheme designed to relocate eligible Afghans who served with the British. It also fails to deliver on the then prime minister Boris Johnson’s pledge in September 2021 that the UK would do “whatever we can” to ensure that Triples members left behind in Afghanistan “get the safe passage they need”.

The denial of assistance to many of these Afghans is currently being challenged in a legal action against the government, The Independent can jointly reveal.

A number of the Afghan special forces personnel are now in the UK after being evacuated, or having travelled through Europe and crossed the Channel on small boats. Some are in neighbouring countries such as Iran and Pakistan, but the majority remain in Afghanistan.

Ahmad is still trapped in Afghanistan after receiving a formal rejection of his claim from the MoD. The rejection email sent to Ahmad on 11 July this year says he is not eligible because he has not “worked in Afghanistan alongside a UK government department, in partnership with or closely supporting it”.

Ahmad strongly rejects this assertion. “Brits were leading our military operations, living with us in the same military camps. We thought we were friends and we had commitments towards each other,” he said. “We thought no one from our unit would be left behind. We thought even supporting staff would be helped, but they betrayed us.”

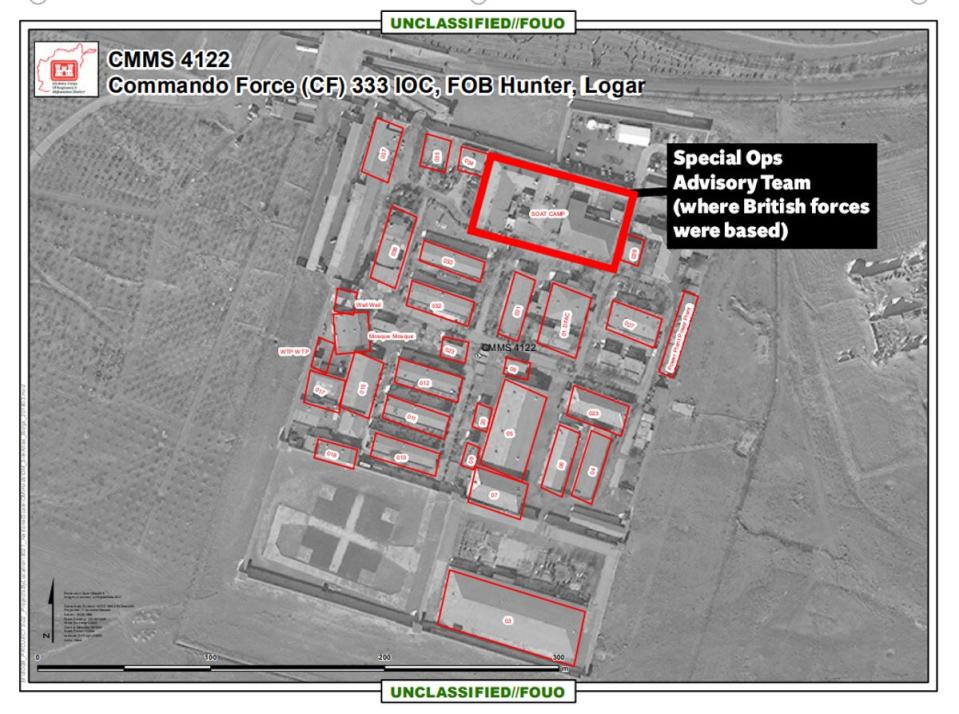

As a sergeant in the 333s, Ahmad ate and drank with his British special forces colleagues in their base in Logar province. He was wounded multiple times on joint missions carried out with the British to raid Taliban hideouts, and – loyal to the end – he was part of a 333 squadron that was deployed at Kabul airport in August 2021 to help with the Nato evacuation.

The former soldier is now in hiding, but he fears that the next time the Taliban catch him, he may not come out alive. Photos taken at the clinic after the attack show Ahmad with a large, bloody gash across his nose and missing front teeth. In a video he sent to his former commander the day after the beating, in which his battered face is covered in bandages, he explains in a pain-stricken voice what had happened.

A campaign of torture and death

Riaz Ahmadzai, a CF333 colleague of Ahmad who was also at Kabul airport providing security during the West’s withdrawal, faced an even worse fate.

Initially it seemed that Riaz, 24, would be OK; he surrendered his weapons to the Taliban, and they handed him a receipt stating that he would be safe. Nonetheless, he tried to be careful, rarely leaving the house. But in April 2023, on a rare outing to buy groceries for his family’s Eid celebrations, he was shot dead in front of his home in Jalalabad.

“There were two of them on a motorcycle. They shot him in the head despite their general amnesty and the promise that he wouldn’t be harmed,” his father said. “He died on the spot. My younger son took him to hospital, but the doctors told him he was already dead.”

Video footage from after his death shows Riaz’s lifeless body on a bloodied hospital bed with a severe head wound. “Riaz got killed because of this previous work with British forces. For trusting British forces, he paid the price with his life,” his father added.

The Taliban got to CF333 sniper Qahraman even more quickly. He had tried to board a UK-bound flight during Operation Pitting – the military operation to evacuate people from Afghanistan – but was turned away and told there wasn’t space. The 29-year-old, whose name has been changed to protect his family in Afghanistan, went to stay at his sister’s home in Kabul as he worked out what to do next.

Three weeks later, he was shot dead outside the house by a gunman on a motorcycle.

Qahraman’s brother Shaheen, who also served in the CF333, had managed to get on an evacuation flight to Britain in August 2021. Speaking from his new home in the UK, he said: “My nephew was there when Qahraman was killed but he couldn’t do anything. He took him to the hospital, but the doctors said he was dead. He had been shot with 15 or 16 bullets.”

In another case, former CF333 sniper Walid, whose name has been changed to protect his family, was arrested during a late-night raid on his home by the Taliban two months after the West’s withdrawal. He was taken to an outpost before being “killed with knives”, according to a relative, who asked not to be named.

The relative said the family discovered Walid the following morning, and that the Taliban finally agreed to hand over his body after negotiations with village elders. “It was not a big funeral ceremony. We secretly did his prayer ceremony with limited people and then buried him... secretly at night,” he said.

Once the Western forces had left, two brothers, Khair and Mohammad, who were also soldiers in the unit, decided their best option was to flee to Iran. But they never got there; as they travelled by car to the Iranian border, the brothers were shot at and killed. They were just 24 and 19 years old.

Nasir, a former sergeant in CF333, whose name has been changed, is said to have been killed by the Taliban in August this year. His former commander, who is now in the UK, said he spoke with him three days before his death, when Nasir told him he had spent two weeks detained in Taliban custody and feared he would be killed.

The commander said: “I spoke with him for one hour after he was released, and he told me: ‘Boss, the Taliban will kill me.’ I told him I would send him money, but it was too late.”

Photos show Nasir’s body in a coffin, his head tied in a white cloth which appears to be covering a bloody wound.

In a voice note he sent to a friend before he died, Nasir said he was worried about joining a Facebook group for Afghans who had worked with British forces in case the Taliban were tracking it.

Others from the Triples units have escaped death but have been left with life-changing injuries from torture. One former sniper, Gul, who had served in the 333s for 19 years, was arrested by the Taliban in July this year and tortured for three days, his cousin said, adding that he was subjected to electric shocks and forced to sit in cold water, leaving him mentally as well as physically scarred.

Gul, whose name has been changed for his safety, had his Arap application rejected by the MoD in June this year.

His brother said: “I wish my brother had died under the torture than struggle with his safety and mental issues now. He was beaten so badly; he was told that he helped the British forces and now the Taliban won’t leave him alone.”

Mirwais, who served in ATF444 for 14 years up until the fall of Kabul, was caught by the Taliban when he took a risk going to see his family during Eid in 2022.

The soldier, whose name has been changed for his protection, said: “They came directly to my home. They beat my family, the children, everyone. And they covered my face and they took me to an unknown place. My family didn’t know where I was for almost two months.” He too recounted being tortured with electric shocks and water pipes. A second former 444 soldier who was detained and tortured by the Taliban at the same time verified Mirwais’s account of torture.

One former group commander in the 444s, Rahim, who was rejected for MoD help, said he had been held in Taliban custody for four months in 2023. His family had to pay thousands of dollars to secure his release, he said.

“When they first arrested me, they put me in a container with no windows or AC. The container was under the sun, and it was difficult to breathe because of lack of oxygen,” said Rahim, whose name has been changed. “On top of that, they would come several times every day with thick electric cables to beat me. When they would get tired of beating, they would give me electric shocks.”

He was eventually taken to Pol-e-Charkhi prison in Kabul, he said. In one incident, “they put a water pipe in my mouth and then turned on the water so I couldn’t breathe. They would put water in a syringe and then pump the water in my nose, it was so painful. They were making me accept that I had cooperated with the British forces, attacked and bombed their houses.

“They were also forcing me to provide names and contacts of other 444 unit members.”

A report by the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, published on 20 September, found that in an attempt to extract confessions or other information, the Taliban had been subjecting detainees to “severe pain and suffering, through physical beatings, electric shocks, asphyxiation, stress positions and forced ingestion of water, as well as blind-folding and threats” – matching with many of the accounts we’ve heard from former members of the Triples.

Brothers in arms – How British special forces fought side by side with Afghans

In 2002, the UK became the G8 lead country in tackling narcotics in Afghanistan. Drawing on the special forces’ experience helping the Colombians tackle their drug trade, that same year, the UK set about creating an elite unit of Afghan fighters, CF333, which would fight alongside the British.

Although the unit of around 400 members was initially a counter-narcotics force, designed to aid the UK in its work taking out the drug production networks funding the Taliban’s terrorism, it later developed sophisticated counterterrorism and counterinsurgency capabilities – helping the British to track down and capture senior Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders.

A few years later, this work was expanded and the British formed the Afghan Territorial Force (ATF444). The two units became known as “the Triples”.

One British former military adviser who worked with the Triples in Afghanistan in the 2000s said: “They were the national force doing the UK government’s bidding. That cannot be more aligned with the UK’s strategic interests. These are not people who just did a bit of translation, made a bit of money and left. They put their lives on the line, properly fighting with us, for us.”

A former UK Special Forces captain who served with the Triples in Afghanistan for several years described it as a “complete symbiotic partnership”.

“We were one unit. We ate together, fought together, died together. The fact that they’re not given special treatment, especially given it’s not a huge number of blokes we’re talking about, is outrageous. You couldn’t work more hand in glove with the British.”

The veteran said that photographs of some of the Triples members who had been killed in combat were displayed on the walls of UKSF offices in the UK – though he wasn’t sure if they were still there.

He added: “We asked them to believe in an optimistic and hopeful future. We promised them the world, and completely failed to deliver in every way.”

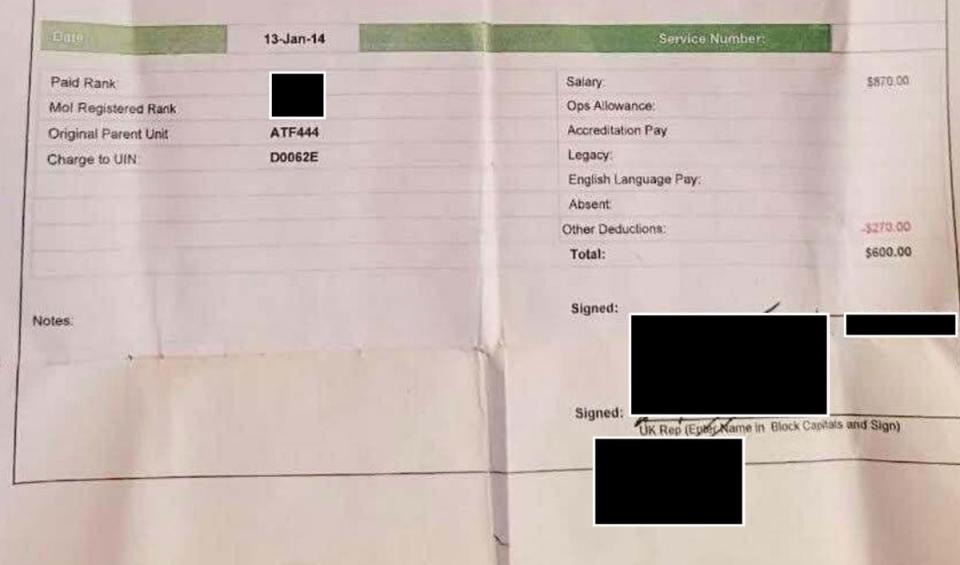

The Independent can jointly reveal that members of both units received a monthly salary from the British government, paid in cash. A few years after they were set up, the units moved to an Afghan government structure under the Ministry of Interior, with the Triples becoming a branch of the Afghan National Police. At this point, soldiers started receiving an official Afghan government salary that was paid into bank accounts, as well as their British salary.

One British former adviser confirmed that the CF333 members received a monthly stipend, with commanders receiving around $1,000 (£824) per month. He said the additional money was designed to “pay for their loyalty” to the British.

As the UK tried to make the Afghan forces more independent, the Triples’ monthly salaries became cash “top-ups” based on rank, with extra payments by mission. The British mentored, trained and paid the 333s until the fall of Kabul in August 2021, while the 444 unit was handed over to Polish forces in 2014.

This “top-up” pay model is confirmed in a 2018 army training manual that has been published online. An “operational bonus” was also paid for each day they were deployed in the field, “resulting in greatly increased enthusiasm to participate in high tempo operations”, the manual says.

A former head of the administration section explained that the Triples would be handed a sheet of paper with the salary or mission payment on it; they would sign it, receive their cash, and then hand the paper back – crucially leaving them without documentary evidence of receiving their salary.

Numerous former Triples have told The Independent that this was how they received their wages.

A document that appears to be one of these “payslips”, seen by this investigation, is written in English, states a salary amount of $870, and bears the signature of a Triple member alongside that of a “UK Rep”.

Colonel Simon Diggins, a former defence attache in Kabul, said the Triples evolved as the campaign in Afghanistan developed, with considerable mentoring and training from the British. “It involved very direct leadership and direction,” he said, adding: “The issue of British payslips seems to be fundamental. It seems to me to be a pretty basic statement that we were paying them. There is no argument there whatsoever.”

A report from the Rand Corporation, a think tank with ties to the US military, detailed a 2013 visit by analysts to the Triples units and noted that the British pay was significantly higher than the amount the soldiers would have received through their regular Afghan salaries. The report considered whether the Afghan special forces were ready to stand on their own two feet without their British counterparts.

One British officer thought not, telling the analysts that the Brits had been “directing” the Afghans, “not mentoring... not giving them ownership”.

The British forces had a separate living compound, but were located within the Afghan base, adjacent to the Afghan headquarters, mess hall and unit barracks. British officers walked freely through Afghan sections of the base, the report noted, and British and Afghan personnel would sometimes eat together.

“The British invited the Afghans here for Christmas dinner. We invited them for Eid,” one Afghan officer said.

A former 333 commander, who was evacuated to the UK in August 2021, described their relationship with British special forces, saying: “We worked shoulder-to-shoulder. They stayed with us until one month before Afghanistan was lost.”

He said that around 30 of his former staff who were left behind had been arrested by the Taliban and questioned about their role in CF333. “We fought for 20 years, a very strong fight [against] the Taliban. The Taliban is targeting 333s specifically. If they find anyone who they know is from 333, they directly kill him,” he said.

Maj Gen Herbert said the fact that former members of 333 and 444 had been denied relocation to the UK on the basis that they didn’t work alongside, in partnership with or closely supporting the UK armed forces was “both disingenuous and unjust”.

“It’s hard to know whether it’s because of the government’s apathy towards this issue or the incompetence of the government departments involved. These units operated in direct support of UK strategic interests in Afghanistan, alongside UK forces, and routinely accompanied by embedded military UK advisers.”

Maj Gen Herbert said members of the two units would have been “feared and loathed by the Taliban in equal measure”, and that it was “inconceivable” that the Taliban would reconcile or forgive former members of either unit, adding: “Abandoning a single member of these units is a national disgrace.”

The Independent, Lighthouse Reports and Sky have received hundreds of documents and photos that have been provided to the MoD by the Triples in their applications for help.

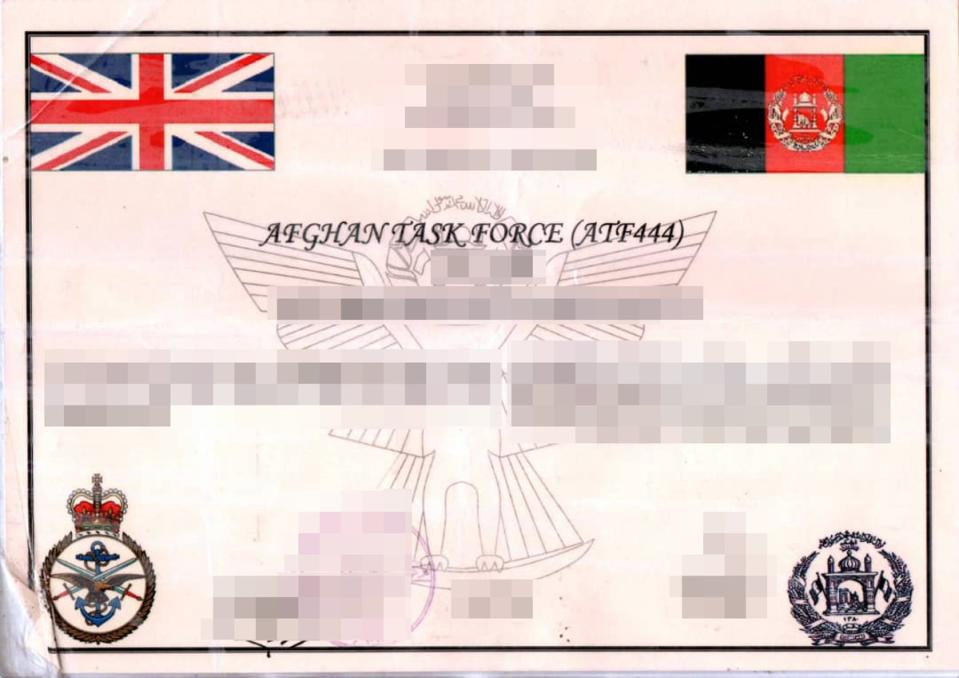

Training certificates for the 444 and 333s are issued and signed by British and Afghan commanders. They bear both British and Afghan flags, and the insignias of both defence ministries.

One member of the 444s had kept a 2010 report sheet that described him as “one of the best all round instructors the ATF has to offer”. The corporal had also been trained in police defensive tactics, such as use of force and firearms, in the summer of 2009, by a major serving as a superintendent in the Hertfordshire Constabulary. He is still in Afghanistan waiting for relocation.

Another CF333 member even managed to provide a recommendation letter from a major in the MoD, along with a picture of himself next to Vice Admiral Tim Frazer, then chief of joint operations, and General Patrick Sanders, now chief of the general staff. The Triples member has been forced to flee to Iran and was rejected for resettlement by the MoD in August.

Photos shared include a photo of a meeting room at the Logar base, which was used by Afghan and British mentors to discuss missions and operations. A photo of a wall in the mentors’ mess hall shows a flag consisting of half of a union jack and half of an Afghan flag sewn together.

One 2013 certificate of appreciation handed to a 444 sergeant bears the logo of the UKSF, the union jack, and a quote from Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Gunga Din”. It reads: “Tho’ I’ve belted you and flayed you, By the livin’ Gawd that made you, You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!” Despite his having worked for the unit from 2006, this sergeant’s resettlement application was rejected by the MoD.

Life in hiding and destitution

The majority of the Triples members are on the run, changing where they are living every few months, which means that finding stable work is impossible.

They have families at home to support, but they are struggling to find money to put food on the table. One former 444 sergeant said: “My kids are dying of hunger because I have not done any job since the fall of Kabul. I am in a different province to my kids. When I visit my kids, I go in the middle of the night, and then in the early morning I flee.

“I can’t get any jobs officially, and I’ve got the bag I’m carrying around. I am looking for empty bottles and metal on the ground. I collect them, and that is how I am surviving.”

Another former 444 soldier filmed the conditions his family are living in. Moving the camera around a bare room, showing nine children and his father sitting on the floor, he said: “This is all the stuff we have, which includes an old carpet and a couple of other things. There are no windows, we have put plastic here to block the hot or cold weather. We are not able to pay for windows.”

In a third case, a man who served in CF333 for 15 years described how he and his family find themselves in a “desperate situation, grappling to secure fundamental needs such as sustenance and shelter”.

The MoD’s refusal to help

Though some members of the Triples were evacuated during Operation Pitting, many were left behind and hoped that the Arap scheme could help them. The MoD said in response to parliamentary questions in September that it could not provide data on how many 333s are in the UK or how many are in Afghanistan. The ministry also said it was not possible to provide an “accurate estimate” of the number of 333s who had died.

According to the government website, the Arap scheme is for Afghan citizens who worked “for or with the UK government in Afghanistan in exposed or meaningful roles”.

Because the Triples were part of the Afghan National Police, under the Ministry of Interior (despite being paid by the British), it is thought that decision-makers have been distinguishing them from those Afghans, such as interpreters or mechanics, who can show that they were formally employed by the UK MoD. Minister James Heappey told parliament on 11 September that “Arap is not explicitly for those who served in the Afghan armed forces alongside the British military; it is for those who served in the employ of the British military in all but a very narrow number of cases.”

However, this position appears to be in breach of the published Arap criteria, which states that Afghans can be eligible if they “worked in Afghanistan alongside a UK government department, in partnership with or closely supporting and assisting that department”, made a “substantive and positive” contribution to the UK’s military objectives or national security objectives, and can prove they are now at risk.

British lawyers are in the process of taking the MoD to court over the rejections, arguing that the process by which former Triples are being denied relocation is unlawful. They say that no explanation has been given for the reasoning behind the rejections, and that concerns have been raised about a potential blanket policy in relation to refusals. The MoD has said it has not issued blanket decisions on Arap applications from any cohort.

Col Diggins, the former defence attache, explained: “The fact that they were technically members of the Ministry of Interior and not employed directly by the British was used in the beginning as a reason for not including them in the Arap provisions. I don’t think that holds any water.”

The Independent, Lighthouse Reports and Sky have found evidence that the Triples’ cases are not even being properly assessed before they are rejected. An internal government document reveals that any Arap application from an alleged Triples member must be approved by the UKSF, which should verify the applicant’s role within the Triples and approve them. However, according to sources within the MoD, the UKSF has been refusing to engage with the process, thus not approving many cases, leading to what are effectively blanket rejections.

One former colonel who served with the Triples in Afghanistan said: “The issue is the units (within UKSF) don’t know who these people are. They don’t really care, they’ve moved on, they’re busy with other things. But these are people who were told they would be extracted, and are still waiting in hope that the UK will be true to their word ... It’s not good enough.”

Tim Willasey-Wilsey, a former senior British diplomat, says he warned the Foreign Office before Afghanistan’s takeover in 2021 that preparations should be made to help evacuate the 333s. His suggestion went unheeded then, but recent discussions with the government regarding the eligibility of former 333 members are proving more positive, he said.

Likewise, the former cabinet secretary and ambassador to Afghanistan, Mark Sedwill, has been lobbying for the government to take the issue seriously. Lord Sedwill has written repeatedly to the home secretary about the abandonment of the 333s, according to chair of the foreign affairs committee Alicia Kearns.

In a recent committee session, Ms Kearns grilled Foreign Office minister Lord Ahmad on why 333 applicants of such “obvious and blatant eligibility” were not being brought to the UK under the MoD’s scheme.

Andrew McCoubrey, director for Afghanistan and Pakistan at the Foreign Office, replied: “There [is], as I understand, eligibility for some members of that commando force under Arap, but not everybody.”

Shadow defence secretary John Healey said: “It is extremely worrying to hear that Afghan special forces who were trained and funded by the UK are being denied relocation and left in danger. These reports act as a painful reminder that the government’s failures towards Afghans not only leave families in limbo in Pakistan hotels, but also put Afghan lives at serious threat from the Taliban.

“Britain’s moral duty to assist these Afghans is felt most fiercely by the UK forces they served alongside. There can be no more excuses. Ministers must fix their failing Afghan schemes.”

Responding to this investigation, an MoD spokesperson said: “The UK government has made an ambitious and generous commitment to help eligible people in Afghanistan. So far, we have brought around 24,600 people to safety, including thousands of people eligible for our Afghan schemes.

“The MoD has never issued blanket decisions on applications from any cohort who have applied to the Arap scheme. All eligibility decisions are made on a case-by-case basis against strict criteria taken in accordance with the Immigration Rules and based on the evidence provided by individuals.”

If the push for reform does not succeed, the government’s hand could be forced by legal action. But even if legal recourse is successful it will be too late for those whose lives have already been taken by the Taliban. Meanwhile, those who are in hiding, like Ahmad, are fearful that they have limited time before they too face that fate.

Reflecting on his service with the British armed forces, Ahmad said: “It’s the famous scenario between Afghans and foreigners; we always think we have become friends, but when we need them, they’re not there.”