'Moonage Daydream' Has Plenty to Show, But Little to Reveal

“Ever since I was 16,” says David Bowie’s disembodied voice at one point in the new film Moonage Daydream, “I was determined to have the greatest adventure any one person could ever have.” While the project by director Brett Morgen—part documentary, part concert film, part long-form music video—conveys the contours of this amazing journey, though, it ultimately adds little to our understanding of a towering artist.

Morgen’s previous films—including The Kid Stays in the Picture (about maverick Hollywood producer Robert Evans) and Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck—have demonstrated his interest in exploding the conventional form of the documentary. Prior to Bowie’s death in 2016, he had met with the singer to present an idea for a sort of alternate-reality biopic; while Bowie didn’t take the bait at the time, after his passing, his manager approached the director and granted him unprecedented access to the artist’s vast archives. Morgen spent the next five years sifting through more than five million assets, including unseen paintings, drawings, recordings, photographs, films, journals, and 16mm and 35mm performance clips.

The choice he made for Moonage Daydream, for better and for worse, was to avoid a linear narrative, to create something that is ultimately about experiencing David Bowie rather than explaining him. The movie is an immersive, sometimes assaultive event, a kaleidoscopic, time-jumping ride through Bowie’s life and work. Other than the occasional question from a television host (some thoughtful, some ridiculous, but Bowie is unfailingly polite and charming regardless), we hear only from the singer himself—no talking heads, nothing from his collaborators, no commentary of any kind. Not so much as a single album title is mentioned, much less anything from the wild range of Bowie’s biography, from the troubling (his flirtations with fascism and, undoubtedly related, his drug abuse) to the transcendent (the incredible renaissance of his final years, culminating in the brilliant Blackstar album coming out the same weekend he died).

It’s easy to understand this decision; there are a shelf full of Bowie books and a number of more straightahead documentaries, including a trilogy of BBC films directed by Francis Whately. But knowing what you want to avoid is different from knowing what you want to say, and by rejecting any sort of context, Morgen’s meditation on this complicated, monumental creator (Bowie was recently named Britain’s most influential artist—in any medium, not just music—of the last 50 years) is largely one-dimensional and repetitive.

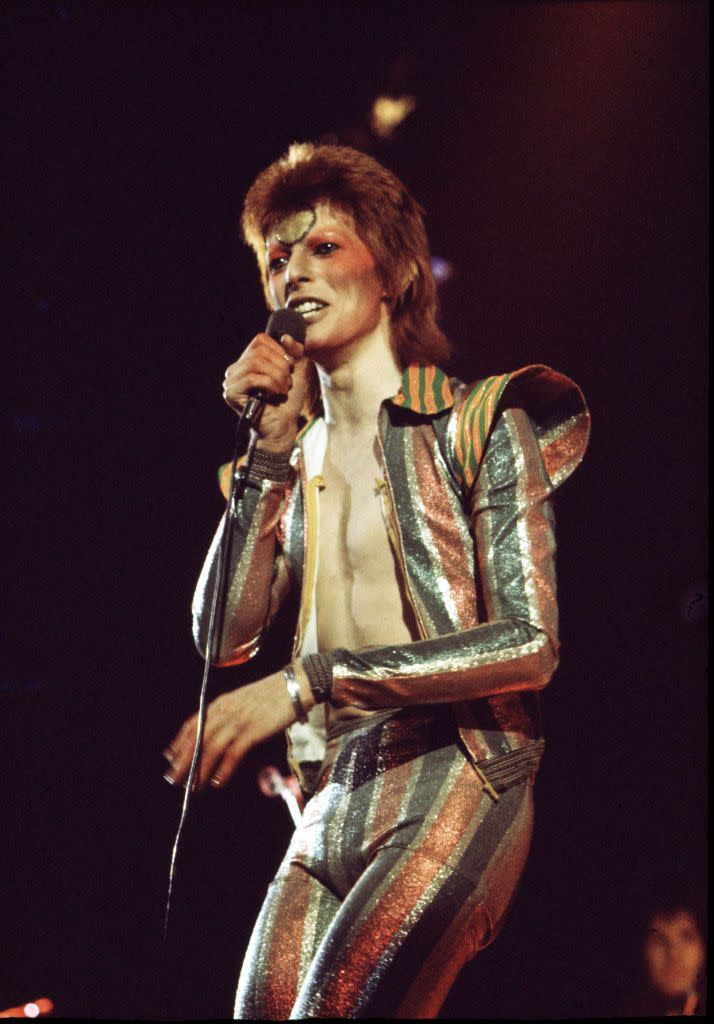

No question, Moonage Daydream is visually and sonically stunning. The footage, whether on-stage or private and intimate, is consistently mesmerizing. At its best, the high-velocity, non-stop cutting offers its own kind of insights, as we bounce between Bowie in concert in full Ziggy Stardust regalia—a gender-bending space alien come alive—to shots of him in the most mundane of settings, standing in the customs line at an airport. The pace often feels frantic, though a few recurring shots and scenes (Bowie painting in his studio, ascending a neon-lit escalator, drifting along rivers and side streets in Asia) offer the chance to catch our breath. (This may also be the loudest movie I’ve ever seen; at the screening I attended, the person next to me literally covered his ears several times.)

Bowie describes his work as “a pudding of new ideas—we’re inventing the 21st century in 1971,” and this sense of ambition, improvisation, and vision sits at the core of the film. He refers to his “inexhaustible supply of extracurricular thoughts.” Of course, it was Bowie’s commitment to constant creative change and perpetual reinvention that was his most important contribution to pop music, and to the culture in general. But this is also the one thing we all know about Bowie, and by presenting everything in the subject’s own voice, Morgen gets stuck on this single idea. We hear Bowie muse on his need to evolve over and over, without any other perspective that might illustrate what was so radical about this attitude, how it actually manifested in his work, why he went certain directions. It not only dulls the impact, but over the course of 140 minutes, it risks becoming boring—something Bowie could never be accused of being.

In a few spots, Moonage Daydream slows down enough to explore a specific moment in Bowie’s life, and things snap into focus. Addressing his childhood, he speaks of his distant relationship to his mother and his fear of following his half-brother, whom he idolized, into mental illness. He speaks of hitting a creative wall and wanting to invent a “new musical language,” which leads to his relocation to Berlin and the release of three groundbreaking albums in the ‘70s. A simple slide show of Bowie’s paintings is a moving moment, a quiet insight into his work that purposefully utilizes the archive to reflect on one aspect of his enormous accomplishments.

But after these glimpses, Morgen returns to frenetically stacking and layering material, often seeming like he’s just trying to cram in as much stuff as possible; Bowie talking over Bowie singing over added sound effects. (Inserting clips from sci-fi movies into a riveting performance of Moonage Daydream’s title track is so obvious it’s kind of insulting.) One of the movie’s themes is Bowie’s use of his art as a way to search for himself—“I’ve never been sure of my own personality,” he says, elsewhere noting that “I’ve always dealt with isolation, in everything I write”—but there’s nothing revealed by simply piling up sounds and images, no sense of how this artist’s intent was different from any other artist or why the screaming, crying fans responded to him so powerfully.

Even when it’s unnecessarily interrupted, though, the performance footage is what ultimately matters, and what stays with you after the film’s two hour-plus runtime expires. Bowie was never less than spellbinding onstage; one of the most striking scenes is a montage of him dancing cut to “Let’s Dance,” and it’s a reminder of how under-appreciated his pure movement was. A few songs are allowed to stretch out—a slow-burn version of “Heroes,” a pummeling rendition of “Hallo Spaceboy” from the 1995 tour with Nine Inch Nails—and time stands still.

Especially with enhanced video and audio quality (the music was remixed by longtime Bowie producer Tony Visconti), this material is simply irresistible. But as dazzling and watchable as it is, Moonage Daydream needed to either tighten its focus or open up its lens—the ride it offers is too familiar for longtime fans, too vague for Bowie newcomers. And experimental and exploratory as he was, David Bowie always had a canny sense of who was watching. “Every artist,” he said, “is a figment of the audience’s imagination.”

You Might Also Like