Mars rover Perseverance's high-tech mission to the red planet

Update: Perseverance is safe on the surface of Mars! The headline has been updated to reflect the news.

Image Credits: NASA

There will be one more robot on Mars tomorrow afternoon. The Perseverance rover will touch down just before 1:00 PM Pacific, beginning a major new expedition to the planet and kicking off a number of experiments — from a search for traces of life to the long-awaited Martian helicopter. Here's what you can expect from Perseverance tomorrow and over the next few years.

It's a big, complex mission — and like the Artemis program, is as much about preparing for the future, in which people will visit the red planet, as it is about learning more about it in the present. Perseverance is ambitious even among missions to Mars.

If you want to follow along live, NASA TV's broadcast of the landing starts at 11:15 AM Pacific, providing context and interviews as the craft makes its final approach:

Until then, however, you might want to brush up on what Perseverance will be getting up to.

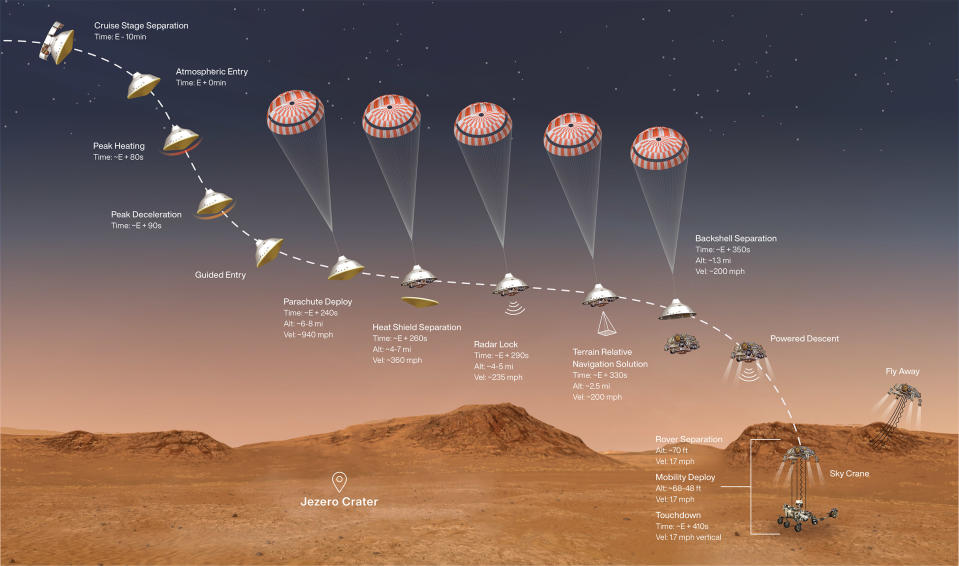

Seven months of anticipation and seven minutes of terror

Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

First, the car-sized rover has to get to the surface safely. It's been traveling for seven months to arrive at the red planet, its arrival heralded by new orbiters from the UAE and China, which both arrived last week.

Perseverance isn't looking to stick around in orbit, however, and will plunge directly into the thin atmosphere of Mars. The spacecraft carrying the rover has made small adjustments to its trajectory to be sure that it enters at the right time and angle to put Perseverance above its target, the Jezero Crater.

The process of deceleration and landing will take about seven minutes once the craft enters the atmosphere. The landing process is the most complex and ambitious ever undertaken by an interplanetary mission, and goes as follows.

After slowing down in the atmosphere like a meteor to a leisurely 940 MPH or so, the parachute will deploy, slowing the descender over the next minute or two to a quarter of that speed. At the same time, the heat shield will separate, exposing the instruments on the underside of the craft.

Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

This is a crucial moment, as the craft will then autonomously — there's no time to send the data to Earth — scan the area below it with radar and other instruments and find what it believes to be an optimal landing location.

Once it does so, from more than a mile up, the parachute will detach and the rover will continue downwards in a "powered descent" using a sort of jetpack that will take it down to just 70 feet above the surface. At this point the rover detaches, suspended at the end of a 21-foot "Sky Crane," and as the jetpack descends the cable extends; once it touches down, the jetpack boosts itself away, Sky Crane and all, to crash somewhere safely distant.

All that takes place in about 410 seconds, during which time the team will be sweating madly and chewing their pencils. It's all right here in this diagram for quick reference:

Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

And for the space geeks who want a little more detail, check out this awesome real-time simulation of the whole process. You can speed up, slow down, check the theoretical nominal velocities and forces, and so on.

Rocking the crater

Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Other rovers and orbiters have been turning up promising signs of life on Mars for years: the Mars Express Orbiter discovered liquid water under the surface in 2018; Curiosity found gaseous hints of life in 2019; Spirit and Opportunity found tons of signs that life could have been supported during their incredibly long missions.

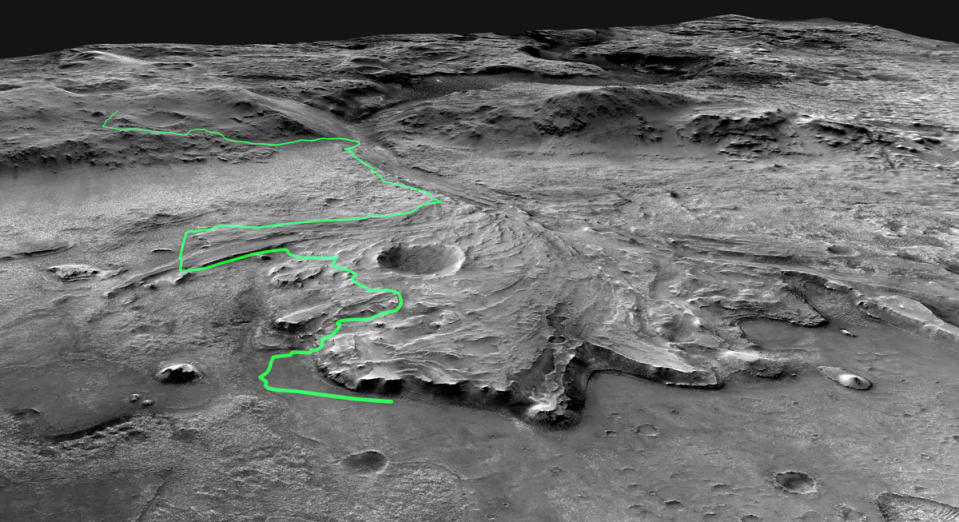

Jezero Crater was chosen as a region rich in possibilities for finding evidence of life, but also a good venue for many other scientific endeavors.

The most similar to previous missions are the geology and astrobiology goals. Jezero was "home to an ancient delta, flooded with water." Tons of materials coalesce in deltas that not only foster life, but record its presence. Perseverance will undertake a detailed survey of the area in which it lands to help characterize the former climate of Mars.

Part of that investigation will specifically test for evidence of life, such as deposits of certain minerals in patterns likely to have resulted from colonies of microbes rather than geological processes. It's not expected that the rover will stumble across any living creatures, but you know the team all secretly hope this astronomically unlikely possibility will occur.

One of the more future-embracing science goals is to collect and sequester samples from the environment in a central storage facility, which can then be sent back to Earth — though they're still figuring out how to handle that last detail. The samples themselves will be carefully cut from the rock rather than drilled or chipped out, leaving them in pristine condition for analysis later.

Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Perseverance will spend some time doubling back on its path to place as many as 30 capsules full of sampled material in a central depot, which will be kept sealed until such a time as they can be harvested and returned to Earth.

The whole time the rover will be acting as a mobile science laboratory, taking all kinds of readings as it goes. Some of the signs of life it's looking for only result from detailed analysis of the soil, for instance, so sophisticated imaging and spectroscopy instruments are on board (PIXL and SHERLOC). It also carries a ground-penetrating radar (RIMFAX) to observe the fine structure of the landscape beneath it. And MEDA will continuously take measurements of temperature, wind, pressure, dust characteristics and so on.

Of course the crowd-pleasing landscapes and "selfies" NASA's rovers have become famous for will also be beamed back to Earth regularly. It has 19 cameras, though mostly they'll be used for navigation and science purposes.

Exploring takes a little MOXIE and Ingenuity

Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Perseverance is part of NASA's long-term plan to visit the red planet in person, and it carries a handful of tech experiments that could contribute to that mission.

The most popular one, and for good reason, is the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter. This little solar-powered two-rotor craft will be the first-ever demonstration of powered flight on another planet (the jetpack Perseverance rode in on doesn't count).

The goals are modest: The main one is simply to take off and hover in the thin air a few feet off the ground for 20 to 30 seconds, then land safely. This will provide crucial real-world data about how a craft like this will perform on Mars, how much dust it kicks up, and all kinds of other metrics that future aerial craft will take into account. If the first flight goes well, the team plans additional flights that may look like the GIF above.

Being able to fly around on another planet would be huge for science and exploration, and eventually for industry and safety when people are there. Drones have already become crucial tools for all kinds of surveying, rescue operations and other tasks here on Earth — why wouldn't it be the same case on Mars? Plus it'll get some great shots from its onboard cameras.

Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

MOXIE is the other forward-looking experiment, and could be even more important (though less flashy) than the helicopter. It stands for Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment, and it's all about trying to make breathable oxygen from the planet's thin, mostly carbon dioxide atmosphere.

This isn't about making oxygen to breathe, though it could be used for that too. MOXIE is about making oxygen at scales large enough that it could be used to provide rocket fuel for future takeoffs. Though if habitats like these ever end up getting built, it will be good to have plenty of O2 on hand just in case.

For a round trip to Mars, sourcing fuel from there rather than trucking it all the way from Earth to burn on the way back is an immense improvement in many ways. The 30-50 tons of liquid oxygen that would normally be brought over in the tanks could instead be functional payloads, and that kind of tonnage goes a long way when you're talking about freeze-dried food, electronics and other supplies.

MOXIE will be attempting, at a small scale (it's about the size of a car battery, and future oxygen generators would be a hundred times bigger), to isolate oxygen from the CO2 surrounding it. The team is expecting about 10 grams per hour, but it will only be on intermittently so as not to draw too much power. With luck it'll be enough of a success that this method can be pursued more seriously in the near future.

Self-roving technology

Image Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

One of the big challenges for previous rovers is that they have essentially been remote controlled with a 30-mintue delay — scientists on Earth examine the surroundings, send instructions like "go forward 40 centimeters, turn front wheels 5 degrees to the right, go 75 centimeters," etc. This not only means a lot of work for the team but a huge delay as the rover makes moves, waits half an hour for more instructions to arrive, then repeats the process over and over.

Perseverance breaks with its forbears with a totally new autonomous navigation system. It has high resolution, wide-angle color cameras and a dedicated processing unit for turning images into terrain maps and choosing paths through them, much like a self-driving car.

Being able to go farther on its own means the rover can cover far more ground. The longest drive ever recorded in a single Martian day was 702 feet by Opportunity (RIP). Perseverance will aim to cover about that distance on average, and with far less human input. Chances are it'll set a new record pretty quickly once it's done tiptoeing around for the first few days.

In fact the first 30 sols after the terrifying landing will be mostly checks, double checks, instrument deployments, more checks and rather unimpressive-looking short rolls around the immediate area. But remember, if all goes well, this thing could still be rolling around Mars in 10 or 15 years when people start showing up. This is just the very beginning of a long, long mission.