Finding Power in a Cinched Waist

Lately, I’ve been ruthlessly cinching my waist. The obsession started with a leather jacket from Phoebe Philo’s rabidly awaited first collection; the coat takes a viciously sharp turn at the drop waist, creating a 90-degree angle at the midsection. Inspired, I found a butter-soft double-breasted vintage leather jacket with a belt on eBay. When I tied the belt at my midsection, using a grip so tight that I launched my spleen into my esophagus, the bottom portion branched out into a severe peplum and I cut a Coke-bottle figure. For the record, I’ve never felt better.

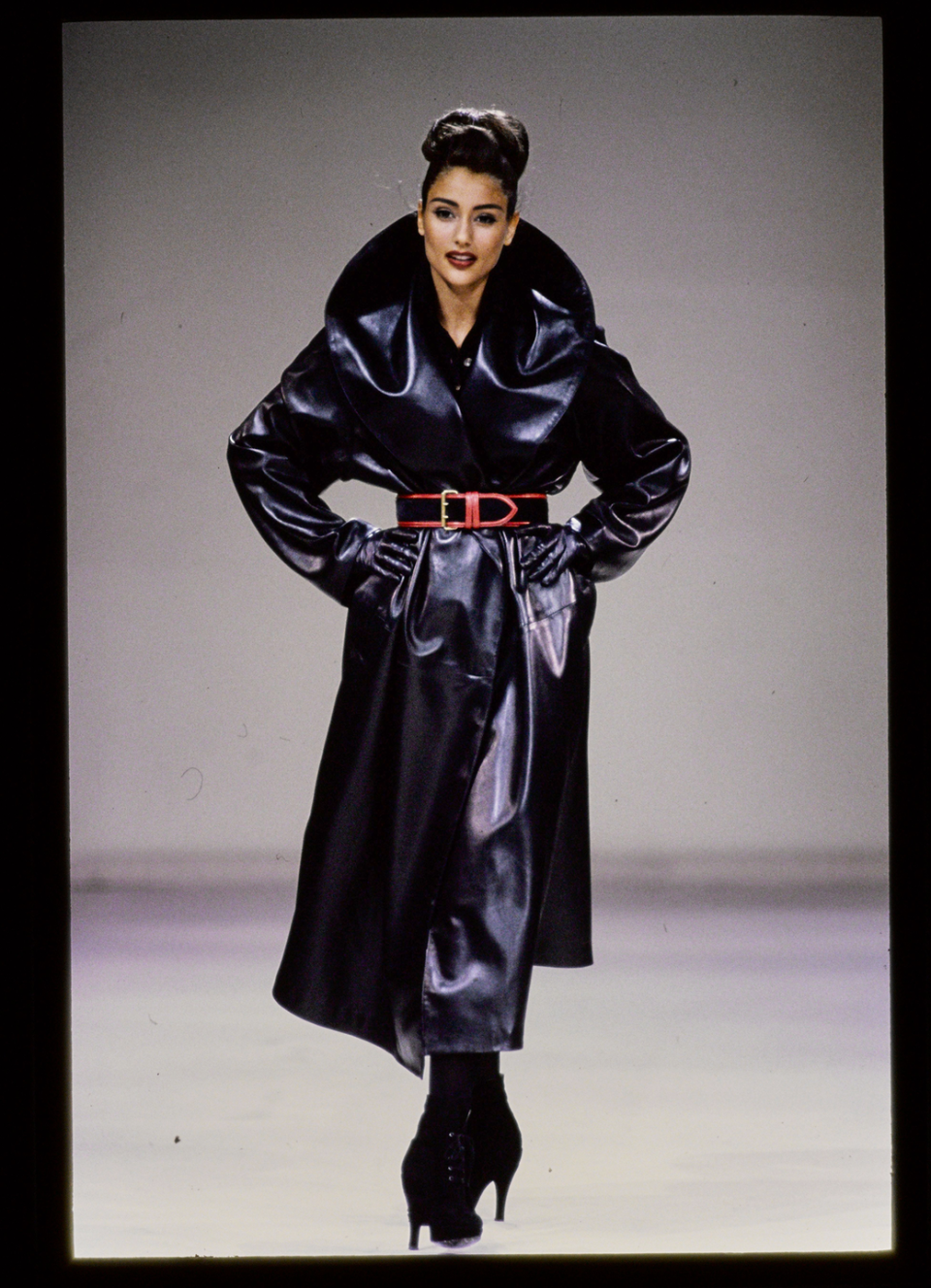

I don’t feel constricted when my waist is tightly cinched. The jacket’s clutch around my torso transforms my most banal tasks into militant missions. I feel a glimmer of Grace Jones in her waist-sculpting leather jacket as I stomp through the supermarket with linebacker shoulders, hunting for fiber-packed cereal. I march to the subway with my whittled midsection like a bootleg Alaïa Amazon, making the stroller-laden Park Slope, Brooklyn, my very own Fifth Avenue. It’s almost as if the jacket demands a destination; there’s purpose in every step. I’ve never felt so womanly. I’ve never felt so in control. I’ve never felt so sensual. I’m like an urban wasp, ready to sting.

On the Spring 2024 runways, others were in tune with Philo’s predilection for the hourglass shape. At Schiaparelli Haute Couture, Daniel Roseberry churned out a black vinyl dress that was sucked in at the belly button, subversively adorned with a Ruth Bader Ginsburg crochet collar. In her final collection for Alexander McQueen, Sarah Burton drew the eye to the midriff thanks to dramatically nipped coats and blazers. Fast-forward to Fall 2024: I spotted a subtle concave shape in a denim jacket from Tory Burch, and at Bally, creative director Simone Bellotti showed skirts with a V shape cut from the waistline down to the navel.

We’ve been living in the binaries of online viral fashion for too long: clout starter packs, trends like “quiet luxury,” and “cores” that spawn microtrends like “lovecore” (Valentine’s Day themed?) or “Barbiecore” (uh, dressing like Barbie). There’s no room for self-expression within typecast boxes. There’s nothing to feel in a “core” generated by the internet. The return of the waist has something to do with wanting to feel again.

Writer Nicolaia Rips has traded her baggy tomboy pieces and girlhood frills for cinched Yohji Yamamoto blazers. “It’s like you’re getting a hug from your clothes,” she says.

Rips isn’t alone; in fact, the incredible feeling of a swaddled midsection goes way back. “There’s a thing with women in dressing that is very tactile and feeling-based. It’s haptic,” says Michaela Clarence, a postgraduate researcher at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. “In 18th-century English fashion, you can feel that relationship between your skin and the clothing, and that kind of forced relationship I think makes you feel as though you are wearing something with a purpose.” There were no doubt, ahem, organ-kneading constrictions that came with the corset, a garment made with the male gaze in mind. Now, the yesteryear garment has gone on to symbolize self-expression—a form of liberation for women who are now choosing to highlight their body the way they want.

When I feel my core, I feel the world around me. This is a far different feeling than attempting to show off my boobs (I have none) or my tush (okay, I have a lot of that) as I desperately tried to in my 20s. While I had no control if my padded bra popped out or my skirt accidentally shifted up a bit too high, there is something about highlighting my waist that makes me feel more agency. “It is that internal relationship between the physical dress and the emotional sense of who you are and what you’re wearing, what you feel like, what you look like together that combines,” Clarence notes.

For many designers, the waist is, quite literally, central to their designs. Jackson Wiederhoeft of the label Wiederhoeft, the high priest of corsets made in New York, mentions that in art school, one of the most important things he learned about shape and form came from the Venus of Willendorf, a limestone carving that’s about 29,500 years old. It is a pint-size statue of a naked woman whose voluptuous body is spilling with curves. From the back side of the statue, the waist has a distinctive V-shaped line. “It’s the first piece of art centered around the feminine shape,” says Wiederhoeft. “I think it’s no exaggeration to speak on iconic feminine artistic archetypes like the Virgin Mary or something where there is a baby at the waist. It is the focus of so much artistic and intrinsic value.”

London designer Dilara Findikoglu has become known for her alluring corsets, worn on their own or sometimes fused with T-shirts. For Findikoglu, much of her sensuality stems from her center. “It comes from the core. It comes from the inside,” she says. She waxes poetic about a documentary she was watching on YouTube that focused on Cleopatra and how the ruler used her prowess to make political moves. “It’s quite fascinating because we carry so much power in ourselves, and sometimes I’m overwhelmed with what I can do in one person’s body as a woman that men can’t. I’m in sync with that core inside me.”

Dressing to show off your waist doesn’t have to look or feel dramatic; it can be a subtle tug here or there. Visually, the waist pulls what could otherwise be a schlumpy look together. Batsheva Hay of Batsheva, who has been churning out Laura Ashley–style dresses for some time, offers the transformative example of adding a waist. Her dresses don’t hang on the body like paisley sacks; instead, they have a feminine bite. “The waist is what originally appealed to me about the prairie dress. It’s like a piece of cotton you can throw in the washing machine, but it has a waist,” she says. “Just that shape … it’s like suddenly you feel fancy and hot.”

Hay has a point: If I didn’t tie my jacket, I’d just be dragging around the city in a leather bag. Instead, I’m fully in control, every cinch of the way.

You Might Also Like