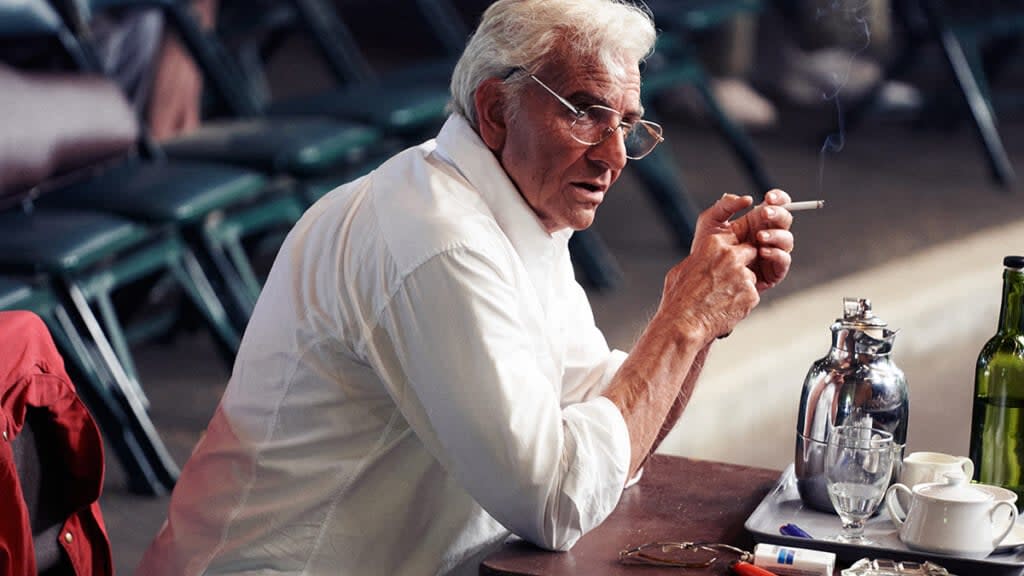

‘Maestro’ Review: Bradley Cooper Conducts a Masterful Symphony With Leonard Bernstein Drama

Easily clearing the sophomore slump and proving that 2018’s surprisingly vibrant “A Star is Born” was hardly a one-off, Bradley Cooper’s “Maestro” bolsters the writer/director/producer/star’s MO as a contemporary jack-of-all-trades with an Old Hollywood soul. Hell, even the Cooper-produced “Joker” pulled from a similar songbook, dusting off reliable American cinema standards and giving them a fresh new spin.

Viewed in that light, this prestige pic’s curious indifference to many of the artistic qualities and career triumphs that made Leonard Bernstein such a coveted biopic subject make a lot more sense. “Maestro” does not go behind the music – it’s here to put on a show.

And in Leonard Bernstein – the only composer/conductor/highbrow-celebrity to earn a shout-out in an R.E.M. song – Cooper sees a similar type. The film tells us right from the start, opening on an aged-Bernstein alone before his piano. At least, that’s how he’s framed, though once the camera pushes forward and swerves ever so subtly leftward we notice a TV crew filming the whole pensive performance. Leonard is a showman, one who so thrives under the spotlight that he doesn’t even close the door to relieve himself. But that’s well enough, for everyone else in his social circle shares the same affliction.

The screen falls dark after that in-color prologue, though we can make out vague traces of light and can hear Bernstein as he takes the call that would change his life: New York Philharmonic conductor Bruno Walter has suddenly fallen ill — now is Lenny’s time to shine. Setting down the receiver, the 25-year-old assistant conductor throws open the curtains, revealing 1940s Manhattan, cast in lustrous black-and-white, then opens the door to his apartment, which somehow goes straight to Carnegie Hall.

From behind the camera, director Cooper stages the film’s opening salvo with the same zeal the actor emotes on-screen. The filmmaker delights in oh-so-perfect match cuts, creates transitions that render the concept of off-stage obsolete and even stages a fantasy musical number as Lenny watches an early rehearsal for “On The Town,” fixating on one of the dancers until lust gives way to his greater desire for attention and all of sudden he, too, is in the show.

Indeed, Bernstein is already part construct, spurting out his words with a ratatat stage patter and a vaguely mid-Atlantic lilt that he readily admits did not come from his immigrant parents. But then his colleague Jerome Robbins (born Jerome Rabinowitz) and sister Shirley (played by Sarah Silverman) can also say the same.

“To conduct an orchestra, you must conduct your life,” advises an alter kaker mentor, and though Lenny turns down the man’s suggestion to shorten his surname to Berns, the words certainly resonate with him when he swaps his lover David (Matt Bomer) for the regal Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan). While the pairing plays to mid-century norms — after meeting at a party, the young actress invites Lenny back to her theater where she finally plants a kiss on him while ostensibly acting a scene — the relationship that soon blossoms is not wholly based on artifice. If anything, they share a love that stems from seeing your partner in full.

Given that “Maestro” mostly plays as a marital melodrama about an all-consuming supernova and the wife in his orbit, Felicia is offered plenty of time to stand back and appraise. In one breathtaking shot, she stands off-stage watching her husband conduct, with Cooper framing Mulligan peeking out from behind a curtain cast with Lenny’s shadow.

Shot by cinematographer Matthew Libatique in a tight 1.33 aspect ratio, the poetic composition reflects the film’s wider interest in aesthetic bravura and – more tellingly — is also one of the very few times we ever see Bernstein at work. Eventually, those two threads come together in a late-in-film sequence where Lenny orchestrates Mahler’s “Resurrection” in a thrumming, unbroken take, as “Maestro” ably pays off the long wait.

By that point, the narrative has advanced to the 1970s, with the film’s palette now in color and the Bernsteins’ marriage in shreds. For nearly an hour of screen time we never leave the couple’s Park Avenue penthouse and Connecticut country home, though given the family’s affluence, claustrophobia never becomes an issue.

What does become a problem, however, is Lenny’s more brazen disregard for keeping his flings a secret and his lovers outside the home. He grows sloppy, she grows apart, and Cooper’s camera grows ever more distant, framing the pair in a series of still compositions shot from afar and leaving a cavern of empty space between the unhappy couple.

As is often the case with actors-turned-directors, Cooper is generous with his cast – including himself. “Maestro” throws up plenty of meaty scenes, with breakdowns, breakups, teary reconciliations and grim medical diagnoses in high supply. While Cooper enters the film as a spark plug, and only turns up the electricity, Mulligan finds time to shine outside Lenny’s orbit, delivering a terrific, introspective monologue as the now middle-aged Felicia reflects upon her own agency in a marriage to a man who never hid his sexual interests. “Who was lying to who?” she wonders.

Even as illness hits, and the film activates tearjerker mode, Cooper finds sharp and subtle ways to ground the pathos. The filmmaker pays particular focus to his two lead’s eyes, following Mulligan’s quiet reactions when a well-wisher pops by to share a happy memory from oh-so-long-ago, and tracking Lenny’s urgent attempt to pull in every detail, to create a new touchstone memory from one of the last happy moments his family shares with one another. Like any good conductor, Cooper knows that the smallest of gestures elicits the most thunderous response.

The post ‘Maestro’ Review: Bradley Cooper Conducts a Masterful Symphony With Leonard Bernstein Drama appeared first on TheWrap.