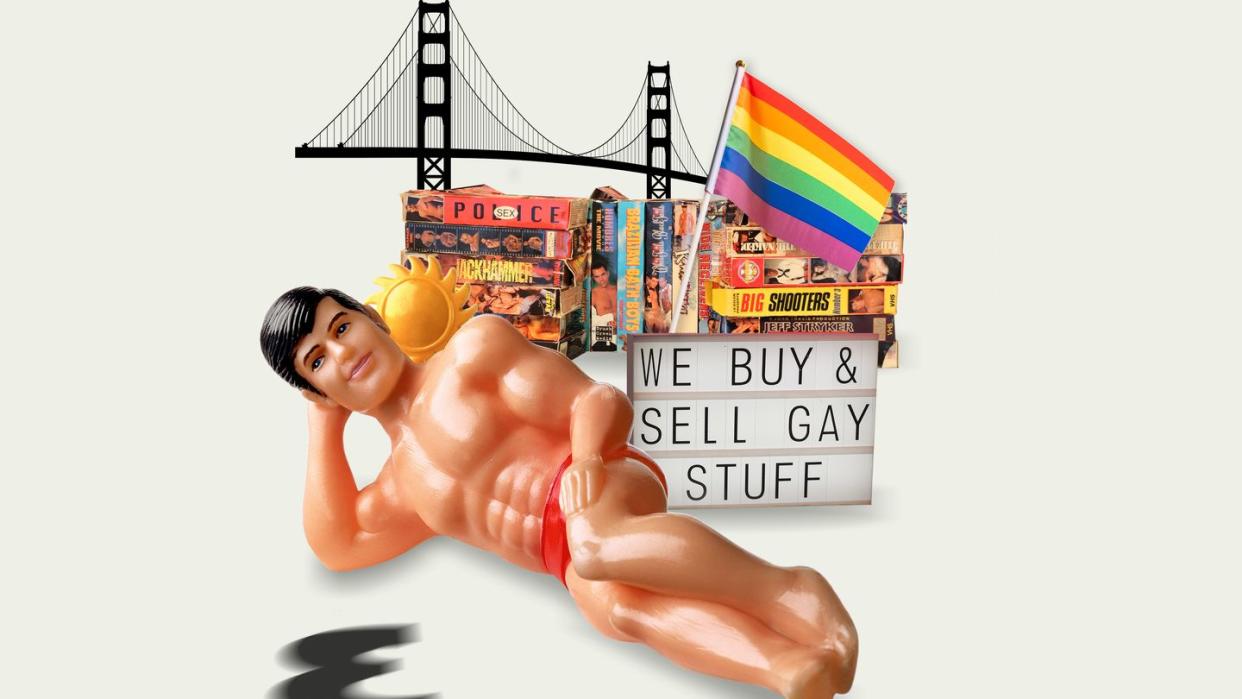

The Last Gay Erotica Store

By the cash register at AutoErotica in San Francisco’s historic Castro gayborhood, a little sign sticks out from a plastic container of Ferrero Rocher chocolates. Have One, it reads, written in pink marker. You’d expect to see the chocolates when visiting your favorite uncle, not in a store packed with so many male bodies on display. The gold foil wrappers gleam against a framed 1970s ad for poppers—a white bottle blasting off through space—and a 1978 poster for a Chicago bathhouse bash. There’s another for the 1988 International Mr. Leather contest. And, of course, there are the dicks. On the walls, slim studs ripped from magazines lean back on couches at full salute. Illustrated Tom of Finland daddies showcase boners spilling out of leather chaps. Framed male nudes flank bins of vintage gay porn magazines with titles like Honcho, Mandate, and Blueboy.

Owner Patrick Batt opened this store in 1996, long before the Starbucks and the SoulCycle moved into the neighborhood. Before the current renewed interest in gay historic material (though for some that spark never died) saw vintage magazines sell for upwards of $100 a pop on eBay. Before the guys wearing ‘80s-inspired short shorts and Chuck Taylors on Fire Island were out of diapers, and before popular Instagram accounts began posting old magazine spreads, with photographers sharing their new pastiche pictorials. Blame the internet for the death of retail stores, but it’s what saved AutoErotica, thanks to the Hail Mary of a GoFundMe drive started by Batt’s friend, photographer Bradley Roberge, during the pandemic. The store is also sustained by its popular Instagram (curated by Roberge), which lures folks in from near and far. New York City. England. As far off as Malaysia, which blew Batt’s mind.

But don’t call AutoErotica—likely the last of its kind in the country—a porn shop, though the draw for many is strolling the vintage skin mags in the front section that overlooks 18th Street. “I’m trying to dissuade people from this being a porn store,” he says. “I would describe it as gay history of which porn happens to be a part.”

Every morning except Sundays, Batt—78, with sharp blue eyes and a neat mustache—hoofs it down the staircase and lugs an A-frame sign that reads, “We buy vintage gay stuff!” onto the sidewalk. To him, “vintage” means things from the 1960s and 1970s, though the store stocks plenty of treasures from the 1990s and early 2000s. Then, he hangs out behind the counter as an old iPod shuffles tunes, from blues to Vivaldi. “Maybe This Time” from Cabaret fades into Depeche Mode’s “The Things You Said.” The store is bright, with white-washed walls and shelves stocked with DVDs and VHS tapes, and signs asking people not to take pictures. Another states, “Prices subject to change according to customer’s attitude.” That’s a joke… probably.

From his post behind the glass cases with vintage pins and other treasures, Batt says he can tell where folks are headed once they hit the top of the stairs. The older guys—and the clientele is almost entirely men—usually head to the DVD and VHS section, while the guys in their twenties and thirties peruse the magazines at the front. Batt is quiet, with square shoulders, a ramrod-straight posture, and a quick wit. A little gruff, though not out of rudeness. It’s clear from his piercing eyes that he’s Seen Shit. As Roberge puts it, “If he feels any sort of threatened, if people blatantly disrespect the store, he’ll kick them out so fast.” Roberge laughs about the chocolates at the cash register, saying that Batt doesn’t even like them. “At the same time, he’s very tender.”

Batt, an “accidental activist,” was born in Wisconsin in 1946. He grew up in a poor family in Wisconsin, raised by a roofer father and a stay-at-home mother, with six younger sisters. At fifteen, he came out, and not long after that, he quit high school and moved to San Francisco with an older man “to get the fuck out of Alaska,” as he puts it. Once that man burned through his cash playing bridge and decided to leave, Batt—at seventeen—turned to hustling in Union Square. “I got ten dollars a pop and a meal to go home with some guy,” he says. “They couldn’t kiss me; they didn’t fuck me. All they could do was blow me. And that’s how I survived.” That park bench is also where Batt, a geeky kid with Coke-bottle glasses, was approached by a photographer. Soon enough, he was on the cover and in the pages of Grecian Guild Studio Quarterly and Trim in 1964. He was paid $7.50 for a shoot.

He bounced around for years before ultimately returning to Wisconsin, where he got a job as a personnel director at the Marion Heights nursing home and also worked with the Gay People’s Union activist group. In 1977, the Catholic Church-linked nursing home found out he was gay and fired him when he refused to resign. Batt sued for discrimination, with his lawyers citing violations of his First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendment rights (as the nursing home received federal funding). The case went up to the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

“I was thrust into the limelight,” says Batt, who had to dodge reporters when they showed up at his house. “But for me it was less about, ‘Oh, I’m gonna be a torch-bearer for gay liberation,’ and more about, ‘How dare you tell me that I’m not worthy of the job that you hired me to do only because you found out I was gay?’”

The Playboy Foundation and Chuck Renslow (the famed owner of gay bars and bathhouses) kicked in for his legal fees. When Batt’s case was ultimately dismissed, Renslow got him a job managing the Gold Coast leather bar in Chicago until the two had a falling out. Then, San Francisco lured him back, first as the general manager of the leather bar The Eagle, then as the general manager of Drummer magazine, a publication for the leather community. It was his time at Drummer, paying bills and finally fulfilling years of customer mail backorders, that inspired Batt to leave and start his own business. He founded the Mercury Mail Order catalogue, which shipped sex toys to customers long before sex shops popped up in every city, and ran it out of his apartment until a small store opened up across from where AutoErotica sits today. If he’d had a friend like Roberge in the ‘90s, in-the-know about the internet, he would have moved Mercury Mail Order online. He could have made a fortune, and he jokes that he’d probably be long retired in Palm Springs by now. Instead, he founded AutoErotica in 1996 and closed up MMO in 1997. At AutoErotica, he started off selling dildos and lube, then switched primarily to vintage materials about 17 years ago.

It’s tempting to push a theme on Batt’s path: on the cover of Trim to working at Drummer, then to running a store where the magazines are collector’s items. Almost as if it’s been his life’s mission to champion gay visibility through these magazines, but that’s not true. “I never had a plan,” he says. “Lookit, I went through the ‘80s, so I didn’t expect to be around in the 2000s, okay? That’s the first thing. Everybody I know is dead. So my reality was, ‘Oh well, I’m gonna die because all my friends have died.’” Maybe it’s a little ironic, he admits. Still, “I didn’t plan on selling vintage stuff,” he adds. “I was only trying to survive.”

That survival instinct is what keeps him up at night when the store’s stock is running low. With no warehouse pumping these magazines out, Batt relies on word of mouth. People come into the shop to sell him things and others call him up when a loved one dies, looking to offload boxes of magazines they found. He prices things much lower than you can find the same magazines online, and even Roberge notes that Batt could charge double. The uptick of interest in vintage material interests him financially, of course. “But it also interests me from a standpoint of younger guys are now going to carry on our history,” Batt says.

Batt might not be romantic about his journey, but he knows his store is important. Roberge knew, which is why he approached Batt out of the blue about the GoFundMe. As much as Batt rebuffed the idea at first—”I went, ‘No no no, that’s like standing on the corner with a can out asking for money, that’s not what Patrick does’”—it raised $16,346 in five months to cover rent and other bills during the pandemic. People who lived nowhere near San Francisco, with no plans to visit, donated. One regular even handed over his COVID stimulus money. It was eye-opening for Batt that people believed in what he was doing; they still do, with visitors telling Roberge via Instagram DM and Batt in person. They offer stories about why they’re buying the certain magazines in their hands. I had this issue under my mattress when I was a kid. Or, I’ve only ever seen online porn before and didn’t know these magazines existed.

What’s so important about these magazines when there’s an endless supply porn online? “Looking back to the '70s and '80s gay culture, there is so much joyous public culture interpenetration between porn, not porn, and culture writing,” says scholar and writer Lee Mandelo, who’s working on his doctoral dissertation at the University of Kentucky; it focuses on digital gay sex culture with an emphasis on the experience of trans gay men. Mandelo is also the author of the historical trans revenge romance The Woods All Black. These publications weren’t just skin mags; they featured travel guides, personal accounts of what it was like to be queer in the military during the early days of the HIV/AIDS crisis, and political think pieces. Plus, the political past looks remarkably like the present. The false accusations about queer people grooming children—largely the basis for over 500 anti-queer bills in America that the ACLU is currently tracking—sound the same now as they did in the ‘70s. “What scares me is that I thought we had gotten rid of all that crazy ‘50s mentality,” Batt says. Far-right Republicans are trying to prohibit access to mail-order abortion pills using the same 1873 “anti-obscenity” law that jailed many photographers who mailed gay erotic materials during the '50s and '60s.

“Sex is very much a place where culture happens,” Mandelo says. “Queer people point it out more, but that’s true broadly. So it feels very important to support a place that is still gathering this kind of work.” And on a less academic note, he adds about the magazines, “They’re fun. Like, I am a gay pervert and I like them.”

Many people snag magazines from the store to leave on their coffee tables like art books, which blows Batt’s mind. Pennsylvania artist Sedgwick Guth, who sees artistry among all the skin, isn’t surprised. “Honcho in particular—when it first started, the covers were literally like art pieces,” he says. “It’s unmistakable by looking at the covers and the spreads that the people who were involved were on top of their game or very accomplished within their field.”

During the isolation of lockdown, Guth mulled over these magazines. For a guy in the 1960s, getting a Physique Pictorial might have been his only lifeline to the wider gay world. That random issue of Drummer is a historical document, chronicling how men looked and dressed; meanwhile, the personal ads in the back described what they were looking for.

“We are not taught our history,” Guth says of queer men. “We’re only really starting to get a sense of what our history is. And these magazines are just one aspect of that.” That thread led him to create oversized mixed-media pieces (over five feet tall and four feet wide) of these magazine covers, the figures captured in vivid detail, larger-than-life. Mythologized and memorialized, with pieces on view in galleries from Boston to Palm Springs.

Others find the physicality of the magazines thrilling compared to the almost mundane parade of digital images that clog our eyes all day. Take LA-based photographer Brian Kaminski, who creates cinematic portraits that feel like they’re ripped from a '70s gay magazine. During the pandemic, he launched an ongoing series of print-only nude portraiture magazines that feature men like actor Matt Wilkas and model Matt Dubbe in places like retro pay-by-the-hour LA motels and mid-century desert homes suffused with gauzy, almost sepia light. “Speaking back to the era of Honcho and other magazines, that’s really why I started this,” he says of his series. “On Instagram, we’re so used to seeing something new every three seconds. We’ve got to feed that eye. Having [a magazine] in your hand and flipping through it is a totally different experience. It feels special.”

There’s a lot of joy at AutoErotica—a shame-free camaraderie where guys nod at each other when they walk in, ask what they’re looking at, or laugh over the political buttons from the years they were born. And Batt jokes with customers. When one guy comes in and asks where he should leave his bag, Batt deadpans without missing a beat, “Right there where it says ‘check bags here.’” That would sound dick-ish if not for the smirk in his voice; the guy hears it and laughs. But after talking and swapping stories for over two hours, something in Batt shifts. He mentions how he was hanging out with Roberge recently when they met two people who’d been friends for 35 years. A thought crystallized in Batt: he had no one like that. He’d stopped making friends years ago—another survival instinct.

“Every once in a while I’ll be sitting watching TV, and I’ll break down,” he says. “Because I wonder, for example, the love of my life, Kenny—what we would’ve done. What our life would’ve been like had he lived.”

He and Kenny Lackey met in 1980 after a night at the bars, when Batt and some friends stopped in at the greasy-spoon where Lackey was a waiter. Lackey left his number for Batt on the bill, which sparked their intense relationship. Batt took on a caretaker-like role for Lackey, too. Lackey called him “Papa” (it’s common in the leather community to which they both belonged for men to call each other “daddy” or “boy"). They hit bumps in the road when drugs got in the way. Lackey moved out, though they never really left each other’s lives. As Lackey was dying due to complications from AIDS a few years later, Batt swooped in to care for him. He even reunited Lackey with his mother, who’d estranged herself from her son due to her religious views, so that the two could say goodbye and maybe find peace.

Nearly thirty-five years later, the loss still catches in his throat and sheens his eyes.

Roberge was the one who encouraged Batt to share his story, which turned into a February talk at the Academy, an LGBTQ+ social club, called “Academy Forum: The Faces of AIDS in the 1980s with Patrick Batt of AutoErotica.” Batt bookended his talk with two stories: meeting Lackey in 1980 and losing him in September 1989. Now, he pulls out a June 1989 copy of Drummer and flips to a spread of pictures of two men—both bearded, handsome, and decked out in leather. Batt’s eyes, the same from Trim, the same eyes that watch his customers, glint up from the page. The other man in the photos is Lackey, his arms around Batt and kissing his muscled shoulder. Months before he died, Batt says, Lackey worked at Drummer magazine and wrote a personal essay about the night that Batt had entered the first leather daddy of San Francisco contest and AIDS fundraiser, held at Chaps Bar. Lackey was at his side.

“I’ll always love my Papa, and I’ll always cherish our special night,” Lackey says at the end of the text.

Batt read the letter at the time. Only a few years later did he read it again and realize, “Woah, this is a fuckin’ love letter. This is him saying what he couldn’t say to me in person.”

He read the letter again in the store, practicing for his talk. He says his sister Cathi Sharp told him to imagine Lackey’s hand on his shoulder, giving him strength. “Reading that out loud was what I had the most trouble with,” he says of that night at the Academy. “I was a mess.”

Not all the stories are about loss, though. When Mandelo dropped into the store, Batt looked at one of the magazines he was buying and mentioned how the cover model lives down the street. He cuts hair now. A few of the magazines are back in some form or another. Blueboy—the first gay magazine that circulated nationwide—is relaunching in December 2024, just in time for its fiftieth anniversary. Physique Pictorial, founded by photographer Bob Mizer, came back in 2017. A small team of volunteers in the historic Magazine building is digitizing decades of Mizer’s work, and preserving it for scholars and fans. A version of Drummer just returned, too.

As we’re talking, Batt stops to help a customer. The guy circles to the glass case and peeks down at a necklace from a gay motorcycle club in England. It’s the very same necklace he spotted last time (he’s here every Tuesday), but Batt hadn’t priced it yet.

“I shined it up for you,” Batt says, “and so I could read it, too.” The date on the necklace is 1985, the year the customer holding it was born. And on the back, visible once Batt polished away the years, is a message.

To my friend George. From Andy.

“You don’t need to wrap anything up, I can just put it in my pocket,” the guy says at the cash register. Then he stops, reconsidering. “Actually, do you mind if I just wear it out?”

The necklace probably catches the light on the sidewalk when he steps out, already warm from his skin. And maybe Batt will spot it around his neck when he sees him again next week.

You Might Also Like