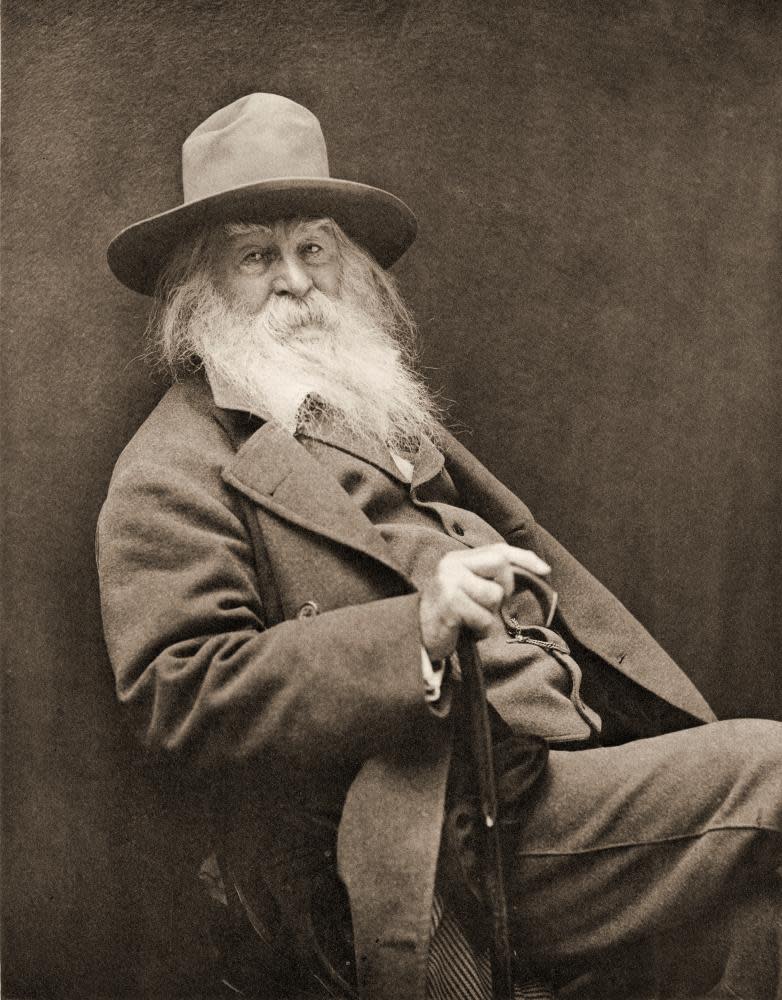

What Is the Grass by Mark Doty review – Walt Whitman and me

“I celebrate myself, and sing myself”: Walt Whitman lived by the unforgettable opening lines of his collection of poems, Leaves of Grass. When the book was first published in 1855, many of the anonymous reviews were later found to have been written by Whitman himself. “An American bard at last!” one of them declared.

The confidence was remarkable, coming from a Brooklyn boy who had gone to school only until the age of 11, and had, in the years before publication, worked through a series of unstable jobs as a schoolteacher, a typesetter, a carpenter and a journalist. But the 12 poems in the first edition of Leaves of Grass lived up to their hype. They seemed to have emerged from a sensibility steeped in “long dumb” and forbidden voices, breaking free, with their plainspeak, their cascading clauses and subclauses, from the older constraints of diction, metre and rhyme. Whitman perceived US democracy itself as a literary undertaking, capable of absorbing anything and everything, projecting its “barbaric yawp to the rooftops of the world”.

A century and a half later, the poet Mark Doty is still overcome by the achievement of those landmark poems. Whitman is not so much a predecessor as a “persistent presence” for Doty, showing up as a shadowy spirit at different moments in his life. At the bard’s house in New Jersey, Doty remembers chancing on a stuffed bird in a glass display case, and glimpsing through its lifeless eyes, a vision of the long-dead poet: “I could smell his warm skin, dusted with talc from his bath.” After a night with a man in an Upper West Side apartment, Doty steals a glance at “my friend’s grey-bearded, sculptured face”, only to find the good grey poet staring back at him. Inside the changing shack of a beach in Boston, Doty is riveted by the proximity to so many naked bodies, and can’t help looking at the room through Whitman’s ecstatic eyes: “It feels like a box of pulsing, masculine life.”

Doty doesn’t find these encounters eerie. Decades spent reading and rereading Leaves of Grass have helped him see Whitman’s best lines as gospel truths – “The smallest sprout shows there is really no death / and if ever there was, it led forward life” – and now he dreams of living his life in their borrowed light. What Is the Grass is a wistful record of a writer’s search for antecedents, and his delight in finding many of his own themes and obsessions prefigured in a well-known literary work. Doty was born in Tennessee, but has spent much of his adult life in New York. In the 1990s, his memoir Heaven’s Coast hauntingly chronicled the tragedy of losing an HIV positive partner. Many of Doty’s own poems are encomiums – to the transience of desire, joy and loss – and in Whitman he seems to have found an elusive counterpart.

Fans of Doty’s poetry will recognise the melancholic mood of certain turns of phrase – the glimpse of a train station in New York like “a temple of fluorescent sorrow” late at night. Doty says he wrote this book to “keep company with” Whitman, and indeed I often had the impression of going through a reading journal, with the short chapters effortlessly switching from a note on Whitman’s vocabulary to a memory of an accident to a glossary of Doty’s lovers.

Related: The best recent poetry collections – review

And yet, for a defence of Whitman, What Is the Grass fails to engage with an aspect of the poet that dates him for many readers. His long, breathless sentences sometimes all too predictably embody what they describe: to “contain multitudes” can after a while feel like a rhetorical device, a way of containing nothing precise. Whitman’s famous poems are populated by character types – the captain, the child, the runaway slave – who are rarely portrayed as individuals in their own right. Subtler distinctions are rendered peripheral when everything is constantly sung and celebrated. As DH Lawrence once wrote about a popular line of Whitman’s (“I am he that aches with amorous love”): “Better a bellyache. A bellyache is at least specific. But the ache of amorous love!”

Doty, too, is often carried away by the bluster – I flinched each time he wrote “sexual congress” instead of, well, sex. He is unironic about his subject’s self-indulgences; he stacks the game unfairly at one point by comparing Whitman’s revolutionary free verse to the stilted cadences of Henry David Thoreau’s poems. Doty is more convincing in moments when he demonstrates how Whitman’s sublimated sexuality and his fascination with death came to shape not only his iconic stanzas but also the spaces between them. His gloss on “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” – one of Whitman’s most accomplished poems – is especially marvellous. He sends you straight back to the text, makes you feel like you’re returning to an old love. You can’t help sidle up to Doty when he wonders in a fit of enchantment: “Have I looked back to Whitman because he has all my life, though I did not know it, looked forward to me?”

• What Is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life by Mark Doty is published by Jonathan Cape (£16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15