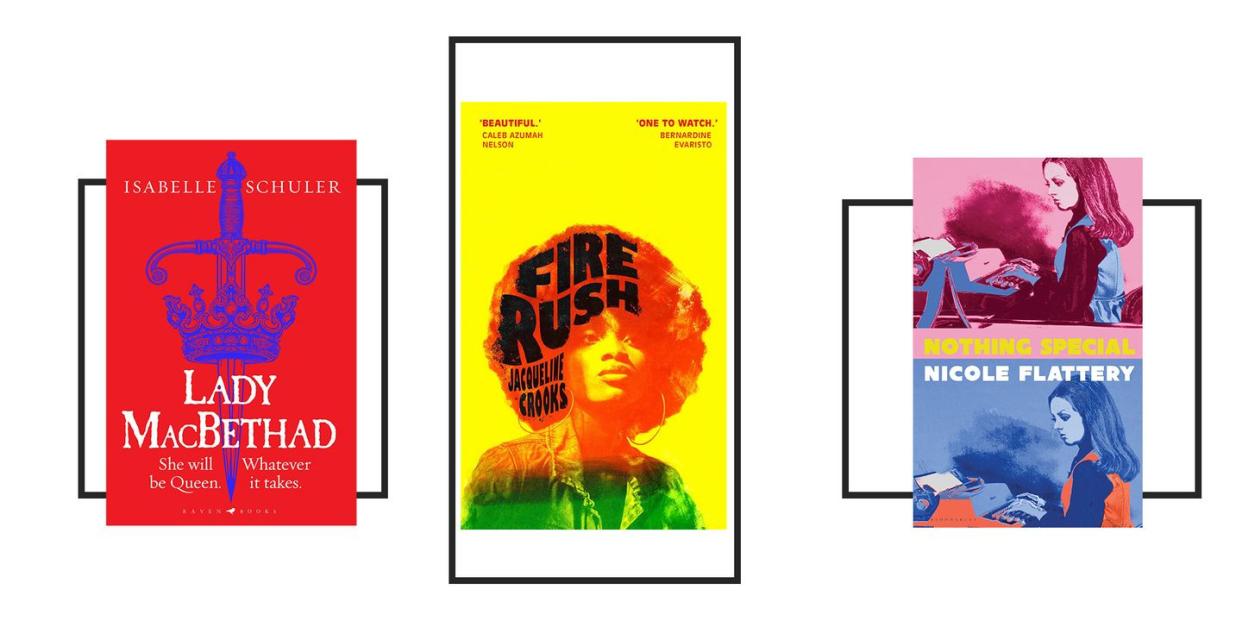

Five talented debut authors to discover this spring

Looking for a good read this spring? Well, thus far, 2023 has more than delivered, with a plethora of entrancing novels to absorb and entertain. As with any year, there is also a groaning roster full of new literary stars, whose debuts are set to stun and sustain you on rainy days and sun loungers alike.

Let these novels transport you to Andy Warhol's Factory in 1960s Manhattan; the cutthroat world of medieval Scotland; the dub-reggae beats of 1980s London; or the heat and aromas of 1950s Hong Kong. From tales of grief to those of hope, of finding oneself and learning the heights of your ambition, these are our top five picks of the debut authors to read this year...

Nicole Flattery

It’s not every day that a debut author receives an endorsement from Sally Rooney. But Nicole Flattery is not every author. The assuredness of her writing belies the fact that Nothing Special – a tale of identity and purpose set in Andy Warhol’s infamous Factory – is her inaugural novel. Yet Galway-based Flattery is no ‘new Rooney’ either. The short story writer, whose 2019 collection Show Them A Good Time had rave reviews, has a uniqueness of voice. “My short stories are so voice-driven, it was interesting to make the transition of that to a novel,” she says, laughing as she adds: “Because you can have a voice for 10 pages, and it can just be like ‘vibes only’ but you can’t be ‘just vibes’ in a novel.”

The ‘vibes’ are, however, strong in Nothing Special. It does an excellent job of evoking 1960s New York, and balances its ideas of voyeurism and longing expertly. The protagonist, 17-year-old Mae, finds herself as a typist at the Factory, transcribing this world of art and hedonism she observes but never truly feels a part of. Warhol is forever felt but rarely seen on the page, as his invocation of fame as an end in itself places a perfect chokehold on the narrative. Fame has long been a fascination of Flattery’s. “As writers we are always trying to figure something out,” she says. “I think that our perception of fame, our longing for it, or our interest in those who have it, is such fertile ground for that kind of exploration.”

Finding her own identity as a novelist proved harder following the attention that her short-story collection received. “People told me what I was good and bad at after my collection [was released], so I thought, well, I have to do this and not do that,” she grimaces. “It was difficult to get all those voices out of my head.” It is a neat mirroring of her work with fame; considering how the opinions of others can cloud your own instincts. When people have a fixed idea of you, how do you write like no one is watching? “That’s what I’m figuring out with my next work too,” she laughs. “Don’t make me more scared that I already am!”

'Nothing Special' is out now.

Wiz Wharton

Perhaps no book on this list has as much of a personal entry point as Wiz Wharton’s astonishing Ghost Girl, Banana. In the process of moving house, Wharton found a box of old floppy discs which she discovered contained the diary of her late mother, who had died unexpectedly in 2009 but who had written ‘My Story’ on these discs. They contained quite the story indeed – the painful, beautiful and engrossing detail of her experience as a Chinese immigrant to the UK from Hong Kong in the late 1950s. Wharton, who had spent countless years trying to publish a novel, decided to make her mother’s story the backbone of her next. “I decided I was going to write it just for mom,” she says. “I just put all my heart into it and I guess that resonated!”

The result, Ghost Girl, Banana, is a deftly handled mystery that is as much about Wharton’s own identity as it is a fictional rendering of her mother’s experiences. Her protagonist, Lily, whose discovery of a mysterious inheritance draws her back to Hong Kong in 1997, is not merely an agent through which we discover the secrets of her mother Sook-Yin’s past (told in neat flashback chapters) but a means of exploring what it means to be Eurasian. The title is a direct reference to the slurs her character – white British and Chinese – receives, viewed as a ghost who is neither one thing nor the other. “It was definitely drawn from personal experience,” she tells me. “Being Eurasian, I never knew quite where I belonged, but I think part of the book is showing that a need for a sense of belonging is universal.”

Now, Wharton is busy writing the screenplay for the TV adaptation of the novel, before she tackles her next book. Yet the impact of Ghost Girl, Banana cannot be understated for Wharton. “Writing the book made me incredibly proud of my mom's legacy, and to be a Southeast Asian author,” she says, smiling. “This is who we are, this is our story, and it is finally being told.”

'Ghost Girl, Banana' is published 18 May but available to pre-order now.

Jessica George

“I know why my other unpublished books failed,” says Jessica George, the much-hyped author of Maame, a warm and moving debut about grief, race and figuring out who you are. “Back then I was writing for the market, writing what I thought would sell. Maame was so personal, it was in the voice that I speak with, so I didn't think would go anywhere. It's been the biggest surprise.”

Her belated authenticity has paid off, quite literally. Maame was the recipient of an almost-unheard of seven-figure deal in the US and an eight-way auction here in the UK. She smiles at this with a winning blend of humility and confidence; a wonderful combination for a young Black female author who has, rather incredulously, been asked countless times if she feels like an 'imposter’. It is an ironically neat echo of her protagonist Maddie, undervalued and underestimated by her family, the recipient of micro-aggressions throughout her career. Yet Maame is not a memoir, and Maddie was a character George took great pains to shape – largely out of her relationship with her character's family. “It is her mother who calls her Maame,” (loosely translated as mother or woman) says George. “In order for her to find out who she is, she has to lose that name, and become Maddie.”

[/product

Despite George’s insistence that it is a work of fiction, she says the largest parallel with her own life is the relationship between Maddie and her father, who has Parkinson’s and for whom Maddie is a carer. George lost her own father to the disease just before she wrote the diary entries that would become the inspiration for Maame. “When you are caring for someone, you have a desire to leave that is then consumed with guilt – a fight that you have to sit with and try and struggle through,” she says. “I think all carers will experience that, because a lot of wanting to leave and live your own life is also wanting to forget that someone you love is going through the worst moment of their life. Having Maddie go through these emotions and experiences, while processing my own grief, was a big reckoning for me.”

'Maame' is out now.

Isabelle Schuler

“Unsex me,” Lady Macbeth famously says in Shakespeare’s play, wishing that she could remove all the attributes of her womanhood in order to murder Duncan herself. Isabelle Schuler, then a young actress, always had a problem with this. “The gendered language around ambition in Macbeth has always struck me as very problematic,” she says. “Why would she take away everything that makes her a woman in order for her to pursue a goal single-mindedly? I know few people more single-minded than the women in my life.”

It is hardly surprising that Schuler turned her attention to the story of Lady Macbeth for her first novel, Lady Macbethad. She had played the character herself and was already a keen student of Shakespeare. “As an actress you really have to get inside your character and really know who she is and how she operates,” she says. “That’s actually excellent preparation for writing a novel.”

Originally a pilot for a TV show, Lady Macbethad morphed into a novel, which she wrote over lockdown. More than merely a revisionist take on Shakespeare’s heroine, it is a deep dive into the story of the playwright’s real-life inspiration for the character: the mediaeval Scottish queen Grouch. Schuler tells me that she adored researching the history, discovering just how eventful this woman’s life really was – one which she has deftly breathed life into to create a warm, smart and compelling historical romp. “You start to obsess about the finer details of rural mediaeval Scotland,” she says. “I have lost sleep over wondering if I put enough sheep in the book. Are there enough sheep?”

'Lady Macbethad' is out now.

Jacqueline Crooks

How do you write music? More specifically, how do you put down on the page the way music makes you feel? That was the challenge successfully met by Jacqueline Crooks, whose extraordinary debut novel, Fire Rush, tackles the world of dub reggae and the power and politics wrapped up in the dance halls of London in the late 1970s. It is a riotous symphony of a novel, one deeply influenced by many of Crooks’ own experiences, which she feeds into the life of her protagonist Yamaye, who finds her identity on the dance floor – and whose love for a mysterious man she finds there leads her on a journey from London to Bristol to Jamaica, on a wave of crime, oppression and police riots.

It is little wonder that, though she has written many critically acclaimed short stories, this novel had sat with her for more than 16 years. “At some point, it begged to be written,” she says, laughing, before explaining that some early false-starts occurred when agents and editors told her to tone down the use of patois. “But alongside the music is the language and it happens to be Jamaican Patois,” she says. “So, it wouldn't have been the same book if I hadn't used that language. It carries the musicality of dub reggae.”

Fire Rush is all the better for Crooks’ insistence on this; it has a cadence all of its own. The author believes that music and literature are “one and the same”, and she sees in both the extraordinary potential to affect change. “As a 15-year-old going to a dance hall back in the day, it did transform me. It felt ancestral; I felt I was drawing on the power from these 200,000-watt speaker boxes,” she remembers. “I imbibed that power and I started to feel a sense of agency because of it.” Now, not only is Fire Rush telling stories of British-Caribbean heritage which have laid dormant for too long, it is unleashing the creative power of Jacqueline Crooks upon the world. When we meet, she is unsure how people will receive her work, but as I write this, she has just been deservedly long-listed for the Women’s Prize for Fiction.

'Fire Rush' is out now.

You Might Also Like