ChinaFile: Much Ado About Nothing

For a brief five hours on April 26, Vogue China and T Magazine China were trending on Chinese social media.

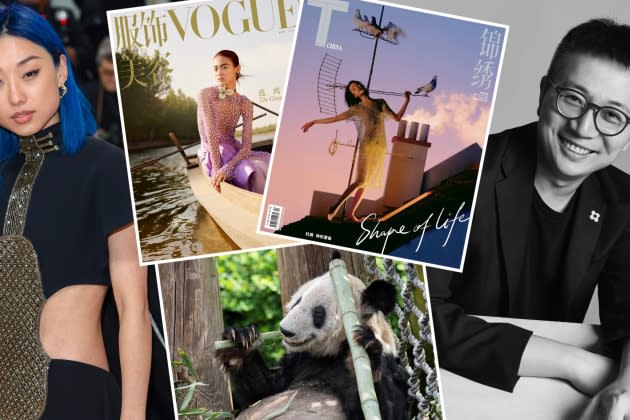

Feng Chuxuan, founder of the Chinese publishing group Huasheng Media, which operates T Magazine and a basket of licensed English language magazines, decided to attack Vogue China’s editorial director Margret Zhang. Feng did not name Zhang in his tweet on Weibo, but he used other tags such as “foreign national,” “Australian,” and “influencer.”

More from WWD

It has been a while since print media trended on social in China. The last incident was pre-pandemic when Condé Nast China’s ex-chief Sophia Liao decided to take her beef with the company public. But even then, it was mainly circulating on WeChat among the fashion circle. The public could hardly care less.

In general, print is suffering in China. Gone are the heydays when Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Elle attracted the bulk of advertising dollars from luxury companies. Nowadays everything is online in China: people buy on the internet, and even Hermès opened a store for its lipstick and perfume on Tmall, the upscale online shopping mall owned by Alibaba.

During the pandemic, livestreaming shops became the newest trend in e-commerce. The format is now live on TikTok in the U.K. and the U.S. Its format is similar to TV shopping networks, except consumers can be their own channel. On Single’s Day in 2021, Austin Li, a top-seller in livestreaming, sold a total of 21.5 billion renminbi, or $3 billion, of goods, double his volume in 2020.

The fast development of social media and e-commerce in China has forced luxury companies to reposition their ad spending, devoting more money to online campaigns.

This is bad news for print. It is worthwhile to note that in China, all fashion print media are owned by international companies, or licensed from them. All social media are owned by Chinese companies. The likes of Vogue have all tried to own their own platforms but there is no chance of them catching up with the number of daily active users on Chinese social — WeChat’s 1.2 billion and Douying’s 700 million.

Fashion print media lacks the connection for Chinese social. In most cases, their social content is some form of video conversion of print — a cover shoot turns into a cover video, etc. So to get eyeballs, try controversy and nationalism, which is what Feng’s Weibo was all about.

“First try earnestly to understand and respect this country, then earnestly try to respect the skills and language of this profession, this is the basics of a professional,” he wrote. “A foreign influencer girl who does not understand public media, an Australian national with the official title of ‘editorial director’ who a few years ago when we interviewed, this kol [key opinion leader] pretended not to speak Chinese. No experience and of international identity. Does that qualify as the leader of an industry in China?”

The background to the tweet is Vogue China’s three-month embargo on celebrities and models who appear on its cover. Feng published an April issue of T with supermodel/actress Du Juan on the cover. Vogue had to cancel its original plan to put Du Juan on its May cover.

So far, Du, who lost a cover, has said nothing. Zhang has not replied, and Vogue’s May issue came out late (with model Fan Jinghan filling in for a last-minute cover swap). It seems that Feng and his T Magazine China are the sole beneficiary of this little snafu.

So why the tweet?

If you are desperate for eyeballs on Chinese social, controversy is the way to go.

For the past five years, it has been a trend for “David” to pick a fight with “Goliath” for some public attention. Unfortunately, there has always been a xenophobic note to these campaigns. Take the one against Lenovo — it was all about Lenovo selling out state-owned interest to foreign financial institutions. The most recent one is a campaign against the Memphis Zoo for mistreating Chinese pandas.

Feng’s tweet has a heavy scent of trying to whip up a xenophobic frenzy about Vogue and Zhang.

Fortunately, the Chinese public is not that stupid after the pandemic. The tweet backfired, with 50 percent of the comments condemning Feng’s tweet as character assassination and below the belt. Feng quickly retreated and deleted his tweet.

Whatever malice was behind Feng’s tweet, one point is valid — is Zhang fluent in the Chinese language? Vogue China had benefited greatly from its previous editor Angelica Cheung’s sensibility and connectedness to Chinese society.

AC, as she is known to Chinese Vogue fans, is equally at ease in both Chinese and English. To AC’s credit, she recognizes the challenge of print in the internet age. She developed a product called Vogue Film, a short film that is content specifically designed for Chinese media. It was a brilliant idea and became very popular with advertisers.

Zhang definitely lacks AC’s keen perception of Chinese society and the ability to create content suitable for Chinese social media. Take Vogue’s account on Douyin, the Chinese TikTok — it has 800,000-plus followers, while the Chinese KOL Chen Caini has more than 6 million. Chen comments on Chinese red carpet dressing while Vogue posts videos of its cover and fashion shoots. It is obvious that localization is an issue under Zhang.

Even though fashion is mainly a visual language, mastery of the written word is still necessary. One can hardly imagine American Vogue appointing an editorial director who does not have an adequate command of the English language, however fabulous his or her visual interpretation might be.

So the question this nasty non-event raised in my mind is: Does Zhang read and write Chinese? Meanwhile, the rest of China has happily moved on to watching an aged panda being airlifted back to China from the Memphis Zoo.

Editor’s note: China File is a recurring column by Hung Huang offering observations of trends in China.

Best of WWD