I created a character called Will then set him running

I never wanted to write a memoir. No, really: I never wanted to write a memoir – or an autobiography for that matter – if such an exercise is understood to be a factual account of the events in my life, and the psychological states associated with them. Nietzsche writes in On the Genealogy of Morals: “Memory says ‘I did that.’ Pride replies, ‘I could not have done that.’ Eventually, memory yields.” And it’s for this reason, among others, that I never wanted to write a memoir: it would be, by my own lights, immoral, to allow my yet vigorous pride to so overwhelm my enfeebled memory – a faculty weakened quite possibly as much by my own active turpitude as any blameless ageing.

But even if my memory were entirely reliable, there remains the sheer inventiveness of my pride, which, no doubt determined – in its own crazed way – to try to make me look good at all costs, would seek to paint up the most discreditable incidents and reprehensible behaviours as way-stations towards, if not enlightenment, at least some sort of … maturity. Yes, I never wanted to write a memoir – and especially not one of those miserable affairs that describes its author’s life as a progression along the road of excess; one that leaves him, Montaigne-like, immured in the tower of wisdom, and writing about it with a mixture of self-indulgence and bogus piety.

I’ve kept a lot of correspondence, journals, agendas and diaries. Moreover, I’m of an age that the witnesses to my life – at least those of my own generation – are for the most part still alive. Surely, given these resources, it might be possible to write a memoir both creditable and true? Possibly – but it certainly wouldn’t be readable, given that the meaning of a life cannot ever be discovered in a mere recitation of facts.

The relation a lived life bears to the black marks on the page is more akin to the way musicians turn minims and crotchets into the sublime craziness, of, say, Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge. Moreover, my life is still being played – and it’s this that makes the “I” of conventional memoir seem so very fictive to me. In thinking about my instinctive recoil from writing a memoir, it’s this “I” that seemed most salient: a sort of bollard of a pronoun, barring the way ahead. I was helped to circumvent it, in part, by a paper I read written by my old philosophy tutor, Galen Strawson, entitled “Against Narrativity”.

Strawson takes aim at two contemporary shibboleths, which relate equally to psychology and literature. The first is that what we’re engaged in as reflective self-consciousnesses is the construction of some sort of narrative. Strawson quotes Jerome Bruner: “self is a perpetually rewritten story”, in order to set up his target – one he swiftly demolishes by an appeal to common sense; how can we be synonymous with the little boy or girl who grazed their knee in the playground 10, 20, 30 years – possibly even a half century – ago? You don’t need to appreciate the paradoxical nature of Theseus’s ship in order to intuit you and that child cannot be in any meaningful sense synonymous – and that moreover, the thinking “I” that has been identified with both of them, cannot be that much more than a sort of temporary persona.

After all, who can he or she be, this person who confidently asserts that they know all about their earlier incarnations? In order to assert this or that about Will-of-the-past, I must assume this “I” to be no mere Will-o’-the-wisp, but some sort of godlike creature – omniscient, omnipotent and, most importantly, standing outside of time, so that he may assert such things, confident in the knowledge that nothing that will happen to him subsequent to the writing of the memoir, will retroactively invalidate it.

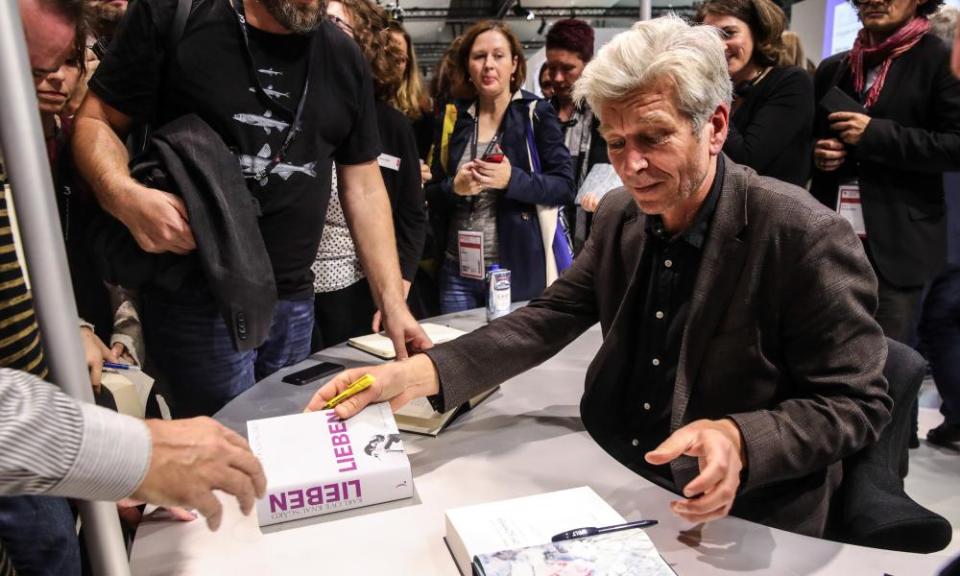

This is why I have little time for the overtly autobiographical fiction of Karl Ove Knausgård – it’s not that I don’t want to hear about the minutiae of this brooding, self-lacerating Norwegian’s life, it’s just that the more he confidently asserts that it was he who did this or felt that, the less I’m inclined to believe him: in his case the problem is surely the raw accretion of detail. I find it hard to try to recall, in true detail, what I was thinking and feeling any given day last week – let alone last month, year, or – gulp! – decade. But Knausgård the writing I confronts Knausgård his younger self with complete lucidity. Each speaks unto the other with a total comprehension that seems, at least to me, resoundingly fraudulent the more exquisite the detail with which it’s limned.

I wonder if, in a way, the popularity of Knausgård’s exhaustively quotidian “struggle” doesn’t reflect the inception of social media during the same period. All those selfies posted on Instagram – all those tweets proclaiming ephemeral (yet passionate) likes and dislikes; all those meals that live forever on Facebook. What are they, if not the multitude conforming resolutely to the dictum that they all have a novel in them? To be specific: an autobiographical novel.

I have more time for Rachel Cusk’s elegant reinventions of her life in her recent trio of novels. She interpolates a version of her “self” into narratives that parallel her own life, without necessarily rubbing against it – so we have “Faye”, a successful writer who’s separated from her partner, and who – in one of the novels – goes to teach creative writing in Greece. I find Cusk’s persona more credible, precisely because I know that the “I” in the books cannot be in any sense synonymous with the thinking “I” that wrote them – there’s too much patent invention in the texts, not least the long and elegant conversations that, were they real, would’ve been absolutely impossible to recall verbatim. In Outline she formally excludes her “self” from the text altogether – an exciting piece of experimentation, like writing Jaws without the shark. Cusk nevertheless obtains her fictional frisson by the assumption of real underpinning: our passage is eased into the fantasy of her life by our assumption of its underlying facticity. Still, one way of looking at this is that we’ve become rather lazy when it comes to the heavy imaginative lifting required to read novels of the purest invention – this, and a preoccupation with the idea of supposed authenticity of voice.

This portrait of my younger self that is not so much warts-and-all, as all warts

This brings me back to my own miserable lucubration. It doesn’t matter if I hide behind philosophical drapes, thrusting a character called “Will” on stage in my place, the reader will still be free to make as negative a judgment of me, the writing, living, 58-year-old father-of-four-adult-children me, as they do of my jejune doppelganger, on the grounds that my stratagem simply hasn’t worked. I wanted to write not a memoir, or an autobiography, or indeed a work of autofiction in which I somehow managed to resolve the contradictions of “my” own past – let alone one in which I tidied up that past, and gift-wrapped it with a ribbon of fancy prose. No, I wanted to depict as accurately as I possibly could, what it was like to be a 17-year-old middle-class boy, succumbing to heroin addiction in the north London suburbs, in the era of punk and Thatcher.

That was all I set out to do. And I discovered when I not only created “Will”, but set him running – like some amphetamine-fuelled clockwork bunny – that he acquired a definite reality of his own. In being thus exteriorised, I could enquire into his interior mental states. As I say: there was actually quite a lot of written material I could’ve consulted – not only my own diaries and letters, but corroborative material from my long-deceased parents, both of them writers. For the most part I eschewed the documentary in favour of the emotive: inhabiting Will’s persona, just as I have in the past those of my fictional protagonists, I propelled him into the unfunny slapstick of hard drug addiction, and registered his emotional and physical responses.

So sharp and enduring were these feelings that I believe they gave me a massive factual shot-in-the-arm: the first person to read the text when it was completed was my girlfriend throughout the period the memoir describes: 17 to 25. Far more lucid and less debauched than I, she considered I had done full justice to the actualité, which includes a portrait of my younger self that is not so much warts-and-all, as all warts. Is this the pride that bases itself on moral laceration, and gratifies itself with creepy self-abasement? I don’t think so – I certainly feel distanced from the Will of Will – and believe that distance enabled a certain pitiless objectivity; with it I hope also comes some objectivity about the wave of heroin use that swept Britain in the late 1970s, and which I believe was one of the vectors that has carried a certain nihilism into the core of our collective being.

However, along with the pitilessness I also have considerable compassion for a young man who was clearly suffering from mental illness, and whose background was at best neglectful – and at worst abusive. Yet Will is no misery memoir – there are too many jokes for that: it may well have been laughter in the face of desperation, but frankly, isn’t that true of all laughter?

• Will by Will Self is published by Viking.