For 33 Years, I Thought Something Was Wrong With Me. Then I Faced The 1 Possibility I Hadn't Considered.

Of all the people I thought I might grow up to be, a lesbian wasn’t one of them. I never fantasized about women or imagined loving them. I didn’t have crushes on women or crave their attention.

I was born in ferociously Catholic Ireland. My mother was very religious. Before getting married, she almost became a nun. I have only one photograph from that time in her life, a novice habit framing her kind, questioning eyes. I imagine her living in the echoey rooms of an old convent, among a colony of young women, their days punctuated by prayer, their heads bowed in reverence toward the god that guided their lives. Her days were embroidered by women, their rhythms and interests, the way women think and talk and feel. That sounds heavenly to me, though not in the way the church intended.

By the time I was born, she’d left the convent, married a man, and both started and sacrificed a career to raise her children and manage a home.

It was the late 1980s, and Ireland was a profoundly conservative place. Married couples were encouraged to procreate, though sex itself was often considered shameful. “Homosexual acts” among men were criminalized. Homosexual acts among women were considered so contrary to nature that they weren’t even part of the legislation. Children screamed “gay” in the schoolyard as an epithet. To be gay was to be stupid, pathetic, worthless.

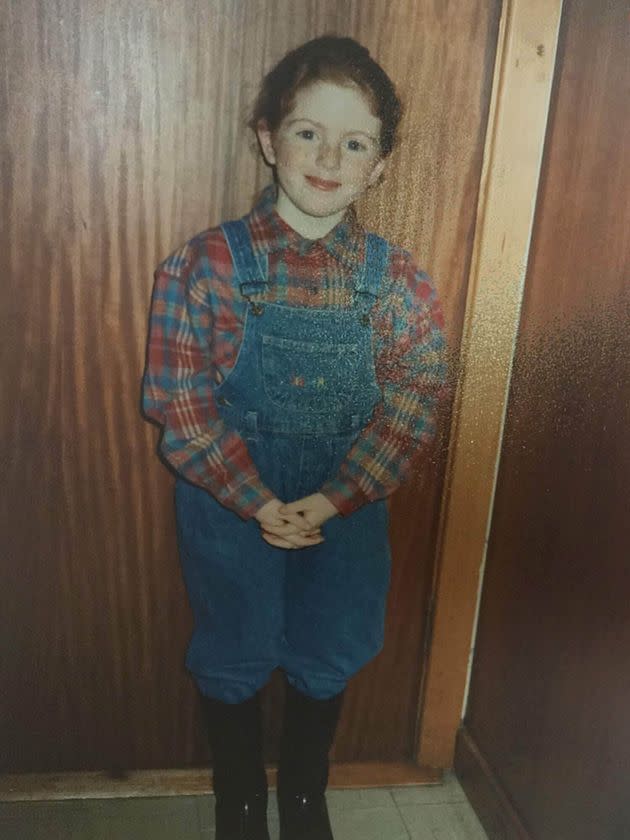

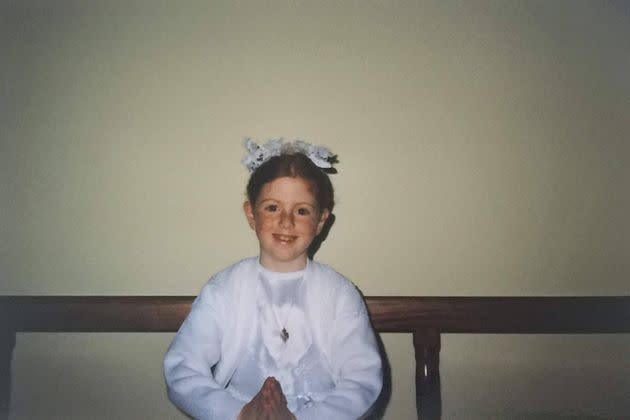

By the time I wore a virginal white dress on my First Communion day, I had already been sexually violated by an adult man. Aside from the perpetrator, nobody knew. I tucked the secret away and continued what everyone told me was a normal, happy childhood.

I repressed the sexual trauma I experienced and set about becoming the kind of girl my mother wanted me to be.

One evening after dinner, my mother had a migraine and went to lie down. I was sitting next to her, chatting about school when she asked if I knew about sex. I, wanting to seem mature, claimed to already know but she wasn’t convinced. She patiently described the physics, how a man would become aroused and insert his penis into a woman’s vagina. My mother’s version of sex education was based only on the mechanics of it. She said nothing about pleasure or consent.

The idea of penetration sent a shot of panic through my body. Looking back, I see this conversation as a breach in the armor I’d built to distance myself from the sexual abuse I’d experienced. In that moment, my body feared penetration in a way that my mind couldn’t understand. I hid my alarm, said good night to my mother and retreated to the other room, quietly scrambling to understand why anyone would ever want to have sex.

I also had sex education in school, but that was heavily influenced by the Catholic Church and the basic message was: Don’t do it! I didn’t have my first consensual kiss until I was 16, standing by a local farmer’s gate, the smell of cow dung rising off the land like fog. The boy’s tongue was thick and frantic. When we pulled apart, I had to wipe his slobber off my face.

I learned about oral sex only when it happened to me. I was 18 and in Belfast, Northern Ireland, for a summer internship when I met an older man. I went back to his flat one night and focused on his high ceilings as he licked between my thighs. I lay frozen, trying to understand what was happening.

“You didn’t make a sound,” the man, who was 29, said afterward. I was disgusted by it — his curly, dark body hair all over me, the damp, sticky spot on the bedsheet where he’d ejaculated — but that didn’t matter. I shook off the nauseating feeling that I’d been exploited and tried to rewrite the narrative. I wasn’t an inexperienced kid away from home for the first time, but a sexually adventurous, modern woman. When my internship ended, I took the bus home and my mother met me at the station. I hugged her tight and tucked away another secret.

A year later, my mother was killed in a car accident.

Within a few weeks, I had my first boyfriend. I met him in college, and he quickly became my anchor in a newly motherless world. Our relationship was fun and loving. We laughed a lot, and he was steadfast when my grief threatened to devour me.

Our sex life was thrilling, but also profoundly triggering. The trauma I’d repressed for so long began to overwhelm me. Visceral flashbacks hit me like scenes from a shoddy horror movie, blended with snapshots of my childhood. Others were sensory. They sprang from some preverbal place, causing my limbs to jerk involuntarily and my heart to race. I’d suddenly be overcome by a full-body queasiness, desperate to vomit but never able to. My body was a haunted house, tripwired with horrible memories. It didn’t feel survivable.

I ended the relationship and didn’t date again for more than a decade. I entangled myself with various men, hungry for intimacy but unable to tolerate the strictures of a relationship. I was only interested in men I could see no future with: the guy who chatted me up while on day release from prison, the guy I met while working overseas, the guy still hung up on his ex.

I was, of course, in therapy. My therapist was a soft-spoken American woman. In one of our many phone sessions, I told her how sex was stirring up the trauma of my childhood. She validated that it was normal to feel disgust interacting with male bodies because I’d been abused by a man.

It was a simple equation: I’d been abused by a man, and so my relationships with them were mangled with trauma. The only way to ease my triggers, she said, was to set down new pathways in my brain and body. I had to expand my experience of sex with men to include respectful, consensual relationships. Looking back, the heteronormativity of her assumption is blinding. But at the time, I didn’t know any better.

I ignored my body’s signals and forced myself to have sex with men. I experienced it only as an observer, watching from the safety of the ceiling as my body performed its erotic pantomime. I ignored the sharp tang of terror that tickled the back of my throat, and capitulated to whatever my partners wanted. The fact that I couldn’t enjoy sex felt like a sign that I was damaged goods, that there was something intrinsically wrong with me. I felt worthless and sex made me feel worse, but the kind of worse that felt familiar. It felt right to me, elementally, to be used by a man for my body.

I was profoundly lonely, in a way that I now know often accompanies being closeted. My friends wanted things I couldn’t understand, their plans and desires orbiting around men and the lives they dreamed of building with them. But it felt alien to me. They imagined lives that were re-creations of the ones that came before, each generation producing another crop of girls who’d grow up to become wives and mothers. They were Russian dolls, reproducing indefinitely, while I felt like a broken toy. I was an anomaly, an outlier who couldn’t fit in.

My life changed in 2015, when Ireland became the first country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage by popular vote. More than 1 million people voted yes. My mother wasn’t one of them, obviously; she’d been dead almost nine years at that point.

But when I watched the news, I saw Irish women who reminded me of her. In broad country accents, they talked about how they no longer agreed with the Catholic Church and wouldn’t privilege one kind of love over another. The day the result was announced, I thought of my mother and cried. Knowing that the vigorously Catholic country I grew up in had chosen, by a significant majority, to allow same-sex marriage upended what I thought I knew about Ireland.

I went out dancing that night, and got “chatted up” by a girl — that’s how I described it in my journal the next morning, gleeful and delirious. I spent the day frantically Googling her half-remembered first name. I clicked through every photograph on the bar’s Facebook page looking for her. I never found her, but a sliver of possibility had opened in my mind.

“If it’s OK to be gay, maybe I might be?” I shook my head abruptly, dislodging the thought. It couldn’t be true. I’d dated men my whole life. The narrative was too neat. Ireland voted to celebrate queer love, and I was instantly ready to embrace my truest self? Life was never that simple.

Looking back, I see that I still had a lot of internalized shame about what it meant to be queer. More than anything, I didn’t want to make a big deal about it. I quietly updated my dating app preferences to include both men and women, and resolved to see what would happen.

What followed was a lot of rejection. I went on first dates with every woman I matched with, but none of them was interested in seeing me again. One ghosted me brutally, after what we both agreed was our best-ever first date. When I saw her outside the supermarket, panic flashed through her eyes before she nodded a curt hello.

I went on dates with many of the men I matched with, too. Several of them were interested in seeing me again, but I was bored by them all. I took a break from the apps and refocused my energy on making friends.

I found queer groups on Meetup and summoned all my courage to walk into rooms full of strangers, rooms I wasn’t sure I belonged in. I was shaky and uncertain, but I kept going. When the COVID-19 pandemic paused the world, I began joining a group of queer women who were meeting in a local park. We christened it Ladygarden. We spent hours there every Sunday, dancing over someone’s iPhone or throwing a tennis ball around. It was so simple, but it was life-changing. Demographically, we were all over the map, but it was the first community where I felt like I made sense. Nobody shamed me for my too-loud laugh, or shushed me to tone down my passion. These women were busy living their joyful, complicated, unconventional lives. I felt at home with them, in a way I never had before.

Coming home from Ladygarden one Sunday, the July sun high in the sky, I pushed the turnstile near my house with my foot.

“This is who I am,” I thought, pausing to swing the gate in the opposite direction. It was one of the happiest moments of my life: the moment I knew I was gay.

I didn’t understand it intellectually, analyzing my experiences in my journal or reading the results of an “Am I gay?” Google search. I knew it in my body. When I made the space to listen, I could hear the still, steady voice inside. The voice that had always known the truth.

Coming out, at 33, was the revelation that clicked my whole life into place. The loneliness I’d felt since childhood ebbed away. I wasn’t broken because I couldn’t imagine a “normal” life. What I couldn’t imagine was a heterosexual life; the rigid trap of heteronormativity made joy impossible.

Soon afterward, I met my now-partner Flaminia at Ladygarden. That first afternoon, I struggled to keep my eyes from wandering to the ravine between her breasts, where her white T-shirt dropped slightly. We quickly started dating.

During our first Christmas together, she took me to Rome to meet her family. When I spotted a picture of Pope Pius VIII on the wall, Flaminia nonchalantly confirmed that he was a distant relative. I thought of my mother. Decades before, she bowed her head to pray in front of an image of the pope. Now, another pope is on the wall of my in-laws’ home amid their family photographs.

My mother never knew me as an out, proud gay woman. My heart crumbles when I think of all she missed out on. I wish I could have taken her to Rome and introduced her to the best, most authentic Roman pizza. I imagine her sitting next to Flaminia on the piano stool as they stumble through the notes of “Hey Jude.” I daydream that, if Flaminia and I ever marry, I’ll see my mother in the crowd, beaming and emotional as I say my vows.

My relationship with Flaminia deepens every day. With her and among our queer community, I’ve found a sense of ease that I never experienced in the heteronormative world. After decades of feeling lost and out of place, it’s a sweet relief to finally feel like myself.

It might have been hard for my mother to accept a gay child, but I believe she would have managed it. All she ever wanted was for me to be happy. My path has been much longer and more circuitous than I ever could have imagined, but I am happier than I thought it was possible to be.

Clare Egan is an award-winning Irish writer. Her work has appeared in Longreads, The Irish Times, Image magazine and several others. She is the founder of Beyond Survival, a publication about life after trauma, and is working on her first book.

Need help? Visit RAINN’s National Sexual Assault Online Hotline or the National Sexual Violence Resource Center’s website.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.