On This 174-mile Trek Across Costa Rica, Stay With Local Families and Learn Cultural Lessons

The best way to experience Costa Rica’s wild side? A walking trail from the Caribbean to the Pacific.

Courtesy of Urritrek

Hikers on the Camino de Costa Rica.The scene felt fantastical, straight out of a Disney movie. Three glasswing butterflies perched on a cluster of billy-goat weed. Orchids dotted the dark green forest canopy. Tiny iridescent hummingbirds flashed across the sky like fairies. Finally, in this moment, was the Costa Rica I’d been looking for.

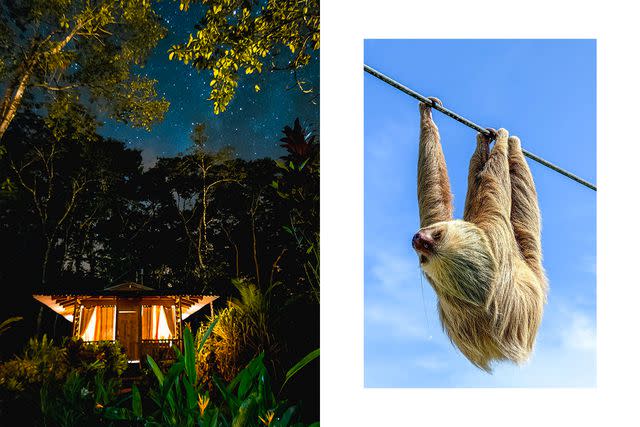

From left: Courtesy of Lirio Lodge; Courtesy of Jen Murphy

From left: A night under the stars at Lirio Lodge, the jumping-off point for the author's trip; a sloth seen along the Camino.Since becoming a poster child for ecotourism in the 1990s, the country has attracted millions of visitors a year, myself among them. But last summer, on what was my sixth visit, I heard more English than Spanish in the surf town of Nosara, and was almost ready to dismiss the country as overtouristed.

Related: The Ultimate Costa Rica Packing List

Hiking the Camino de Costa Rica this year proved me wrong. Managed and promoted by the nonprofit Mar a Mar Association, this 174-mile-long trail stretches across the entire country — from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean — and offers an experience far from the tourist hubs. The 16-stage route spans five separate microclimates, and passes through remote villages, Indigenous land, protected natural areas, and more than 20 towns that up until now have benefited little from conventional tourism. Along the way, trekkers eat and sleep in local homes and family-run lodges.

Courtesy of Urritrek

A distance marker along the Camino.A walking safari, a culinary tour, and a cultural deep dive rolled into one, the Camino is also physically challenging. While travelers can technically walk it by themselves, it’s wise to hire a guide: the trail is isolated, and there are lots of prickly and poisonous things along the way. I also found it helpful to have someone who could field questions about the mind-boggling flora and fauna.

I began my journey in Barra de Pacuare, a jungly village near the Cariari National Wetlands, a protected mangrove swamp and marine area on the eastern coast. After a breakfast of eggs and gallo pinto, the Costa Rican version of rice and beans, I took a 15-minute boat ride to the remote village of Parismina, so I could symbolically dip my toe in the Caribbean. When I arrived, as if on cue, a troop of white-faced capuchin monkeys started performing acrobatics in the palm trees above me like an official send-off ceremony.

Courtesy of Urritrek

The Indigenous village of Tsiöbata.Sixteen days is the suggested time to walk the full trail, but I only had five. UrriTrek, one of several outfitters that run Camino trips, customized an itinerary that included several car transfers, so I could cover more ground. The company also paired me with Juan “Juancho” Chavarria, one of its owners. A bear-size man with a tattoo of a red hummingbird — the route’s mascot — on his forearm, Chavarria has walked the Camino 35 times, possesses encyclopedic knowledge of its biodiversity, and knows its community partners so well that he told me he considers them family.

Chavarria and I hiked back to Barra de Pacuare. It was less than two miles, but in that short span I ticked off half my wildlife wish list: sloths, strawberry poison-dart frogs, howler monkeys, and emerald basilisk lizards. A 20-minute boat ride through thick mangroves delivered us to the village of Goschen; from there, we drove another few miles to the nearest trailhead.

The hike ahead of us was a true adventure, and would take us to Tsiöbata, a village that belongs to the Cabecar people, one of the most isolated Indigenous tribes in the country. After descending downhill through dense jungle for an hour, we reached a roaring river full of rafters. To cross the 400-foot-wide Pacuare River, we had to squeeze into a rickety metal basket while Chavarria pulled a metal towline. “You always have to work for the best parts of the Camino,” he said, wiping sweat from his brow. It was another hour of slogging up a steep muddy hill before we reached Tsiöbata. Leo Martinez, the village’s ecotourism leader, showed us the new museum, and over lunch at the local school, he shared aspirations of hosting craft workshops to bring revenue to the community.

The next day, a guide named Isabel Umaña took over for Chavarria as we traversed the Copal Reserve, a biological corridor connecting Tapantí-Macizo Cerro de la Muerte National Park and La Amistad International Park. After rattling off every species of orchid blooming around us, Umaña pointed out the glasswing butterfly that so transfixed me, then a giant leaf known as a “poor man’s umbrella,” and then the scarlet rump of a male Passerini’s tanager. We hiked out of the wilderness and into the hamlet of Purisil, which, like many of the places we visited, was arranged around a school, church, and soccer field.

Having logged more than 10 miles and some serious elevation, I was ravenous when we reached La Cuchara de Mariana, a humble yet inviting restaurant where the owner, Mariana Céspedes, greeted us with a warm “Buen camino” and cold lavender-scented towels. The feast began with soup studded with green plantain, chayote, and sweet potato; then came a whole roasted trout, followed by coconut-milk caramels.

The Camino’s network of impressive restaurants and lodges is the work of Mar a Mar and Conchita Espino, a retired World Bank officer. She and her husband were inspired to carve out the trail after completing the ancient Camino de Santiago pilgrimage in Spain. Espino and members of Mar a Mar spent 10 years visiting far-flung villages and recruiting locals to create services that cater to trekkers. The trail, though just five years old, has generated not only revenue but also immense pride.

For the next three days, we hiked through cloud forests and jungles, crossed coffee farms and banana plantations, soaked in natural hot springs. I also ate some of the best food I’d ever had in Costa Rica, including fresh-made blackberry ice cream in a home in the Palo Verde cloud forest, a 1,700-acre private reserve with more than 100 species of birds.

On the final day, we hiked five miles uphill from the hamlet of Naranjillo to get our first glimpse of the Pacific Ocean, then hiked two miles downhill to Esquipulas, a small town in the foothills of the Brunqueña mountain range. We cooled off with a dip in a waterfall and finished with lunch at Esquipulas Rainforest, a glamping retreat and coffee plantation. As we relaxed, a bouquet of hummingbirds began to feed on the flowers of a nearby banana tree. In the past few days I had seen more hummingbirds than humans. It turns out, the Costa Rica of my imagination did exist. It just took a bit more effort to experience it.

16-day trips on the Camino de Costa Rica with UrriTrek from $1,950.

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.