Writ in water, preserved in plaster: how Keats' death mask became a collector's item

There’s no mention of John Keats’s name on his tombstone – in fact you might accidentally pass right by it while strolling through the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome, were it not for its distinctly dour epitaph. “Here lies one whose name was writ in water,” is the bitter description, etched at Keats’s dying request, the final sentiment from a poet who believed his words would fade into oblivion.

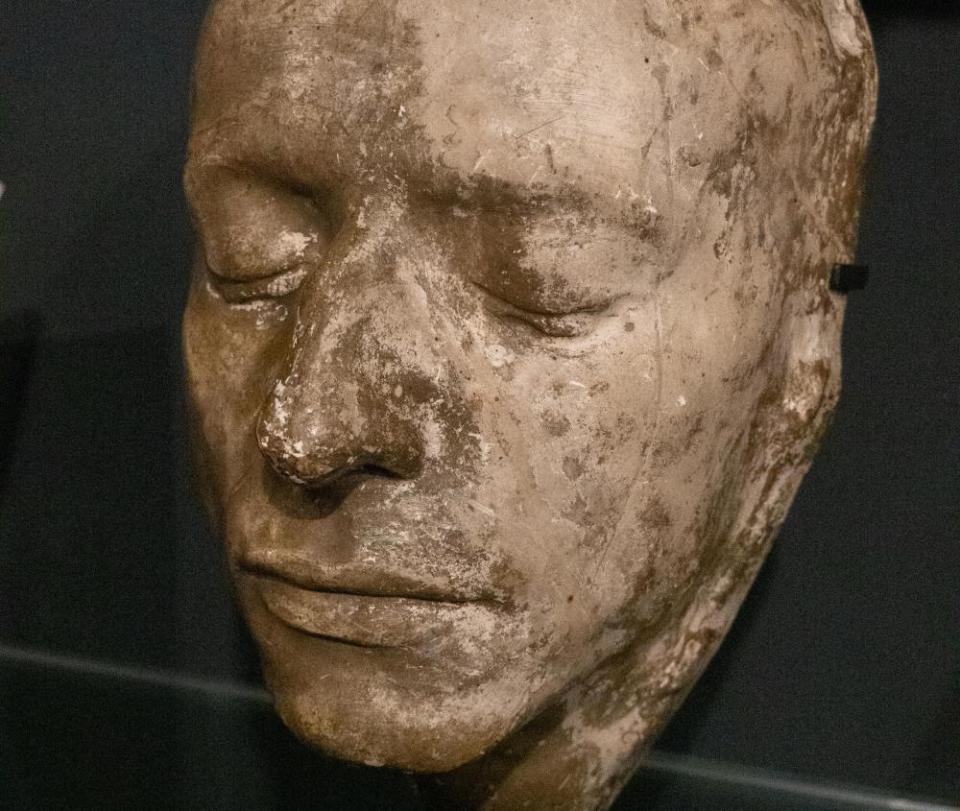

When Keats died from tuberculosis aged 25, on 23 February 1821, the furniture in his room – now a museum – was burned. But his face was shaved and prepared, so a plaster cast could be applied to preserve his likeness. Now, 200 years on, two versions of Keats’s death mask produced by two castmakers circulate galleries, auctions and private collections for large sums. Their value is a testament to Keats’s enduring appeal; Where the Wild Things Are author Maurice Sendak owned one and would reportedly take it from its box next to his bed to stroke its forehead.

In December, Adeline Johns-Putra, a professor of literature specialising in British Romanticism, rode in a taxi with Keats’s face sitting on her lap, having paid £12,500 in an online Christie’s auction for his death mask. “I was in the presence of rare beauty,” she says. “I was so emotional.”

She fell in love with the sensuousness of Keats’s words as a teenager and credits the Romantic poet for her career choice: “I thought it was amazing that you could evoke these kinds of feelings, and these images. It’s so rich, everything from ‘bubbles winking at the brim’ to ‘bursting grape on your tongue’. It’s so, so sensorial.”

Two masks were made from the original mould in 1821. One was kept by artist Joseph Severn, who used the resemblance to paint a portrait of the poet; the other went to Keats’s publisher, John Taylor. Both of these were lost – but the death mask purchased by Johns-Putra was produced by Charles Smith and Sons, which made several casts of the mask around 1898 to 1905. Christie’s now estimates that there are only nine Smith casts remaining.

Related: John Keats: five poets on his best poems, 200 years since his death

The second modern source of the mask was the Parisian castmaking firm Lorenzi, which continues to make copies using a rubber mould. It is unclear how many Lorenzis are in circulation and, as they lack the inscription “Keats” on the throat (visible on the Smith cast), they are not as highly prized.

Peter Malone spent more than a decade tracing the history of Keats’s death masks, after discovering one in the window of a secondhand bookshop in 2001. That copies of the mask eventually reappeared is a sign of its worth, he says: “For the mask to spend 80 years in the dark means that someone valued it and knew its identity, otherwise it would have gone the way of most plaster.”

Keats also had a life mask made in 1816, five years before his death, allowing us to observe how the wasting disease affected the poet’s appearance. “The nose is more aquiline in the death mask. I would say that the cheeks are a bit more sunken. I think the bone structure’s a bit more evident. These are rather to be expected,” Malone says. “Some people probably think it’s a little bit morbid, but I think it is a very beautiful object.”

Aware of the public responsibility that comes with private ownership, Johns-Putra says she plans to share the mask with fellow Keats scholars and lovers. “What I’d really like to explore is loaning it to a museum of some sort, so that other people get to see it,” she says. “Four of them are now in private hands, and that just doesn’t seem entirely right. If we weren’t locked down in a pandemic I’d be inviting any colleagues or students to come and look at it and feel it.”

On Tuesday night – the bicentenary – she drank claret – one of the poet’s favourite drinks – and read some of his work, in the company of the mask.

“It’s an odd feeling, having something you didn’t even dream you’d have,” she says. “There’s this odd sense of feeling very close to a poet, a figure who you’ve always loved – a very deep sense of pleasure and delight. Maybe that’s a really Keatsian emotion to have.”