World War I in colour: How Peter Jackson made 100-year-old footage look brand new

Additional cinema screenings of They Shall Not Grow Old are taking place across the country on the 9, 10 and 11 November ahead of the TV broadcast on BBC 2 at 9.30pm on Sunday, 11 November. Check local listings for details.

Peter Jackson, the visionary filmmaker best known for his adaptations of The Lord of The Rings and The Hobbit trilogies, has taken a break from directing Hollywood films, dedicating the last four years to the First World War Centenary.

The 56-year-old New Zealander was the creative force behind The Great War Exhibition in Wellington, an extensive and immersive look at the First World War that spanned 1914-1918, featuring many items from the filmmaker’s personal collection of artefacts from the conflict.

Read more: Peter Jackson: ‘Great War veterans didn’t want our pity’

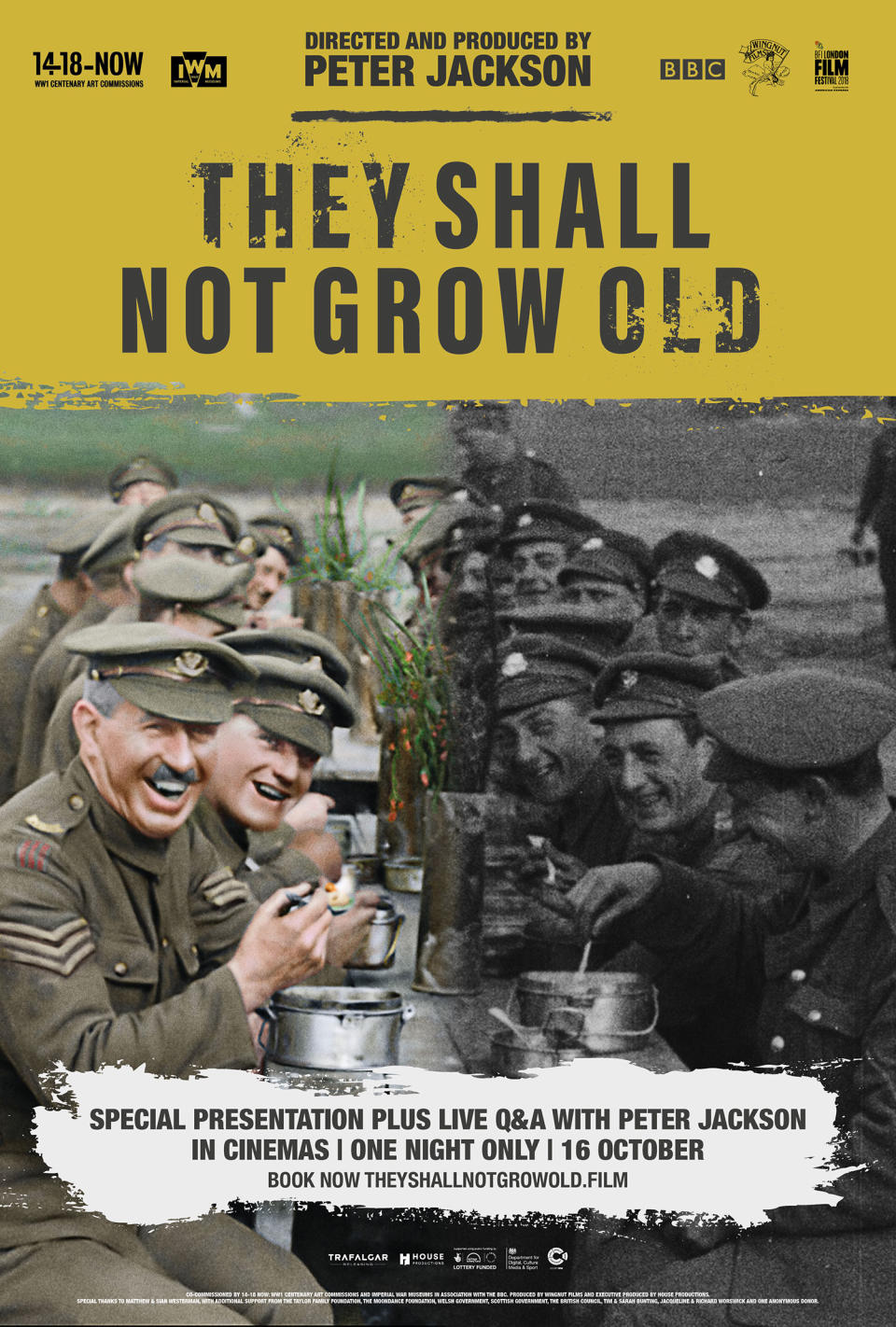

The centrepiece of his work commemorating the end of the Great War though is They Shall Not Grow Old, a startling new documentary. The feature-length film (in cinemas 16 October for one day only) combines restored archive footage shot during the conflict with veterans’ interviews captured in the 1960s by the BBC, bringing the stories of the men that fought in the war to life like you’ve never seen or heard before.

The film footage, shot largely on the front line, has been painstakingly cleaned, colourised, converted into 3D, and given audio by Jackson’s team.

The final effect is astonishing. Watch a taster of the converted footage below.

Where once the shaky, grainy, over-cranked, silent footage alienated modern viewers, placing the events of the Great War in a bygone era, this new footage looks like it could have been shot yesterday.

The Great War is now bright, vivid, full of life, humour, and humanity, bridging the 100-year gap in an unprecedented way.

It was a mammoth task though for Jackson, and visual effects company Stereo D who handled the conversion, and they needed to get their hands on as much footage as possible.

“I wanted to have as much [film footage] as I could,” Jackson tells Yahoo Movies UK. “Because you just never know. I didn’t want it to be limited, by saying ‘give me some of your best film’. So I just asked the IWM [Imperial War Musueum] to give me everything they had, within reason.”

“I think we must have ended up with over one hundred hours of film and we ended up with about six hundred hours of audio, from veterans’ interviews.”

How the footage was restored: Transformation

The restoration of the film fell into three key phases – transformation, colour creation, and stereoscopic 3D conversion.

“The public’s interpretation of that time is heavily influenced by the quality of the historical footage available; black and white, scratched up, highly deteriorated material that has been ravaged by time,” explains Milton Adamou, Stereo D’s Head of Post and Colourist for the project.

“It was our job to eliminate these restrictions by transforming this material to the highest standard, and thus contextualise the historical records in a modern, more vibrant and lifelike way for the first time.”

The Imperial War Museum sent everything they had to Park Road Post, Jackson’s New Zealand-based post-production facility, where artists completed an initial black and white levelling pass on the original images. Some footage was too bright (overexposed), some too dark (underexposed), so this first process aimed to make all the original black & white footage look the same, or thereabouts.

(Use the slider above to see the footage before and after restoration)

Next came the process of cleaning up the footage to remove dust, scratches, tears, chemical marks, and other defects. The footage was then all standardised to smooth out the level of grain – the subtle texture of film – as some footage was very grainy due to its primitive nature, while some needed more grain to make it appear sharper.

Finally, Stereo D then had to retime all the footage. At the time, film footage was shot at 13 frames per second, as opposed to the modern standard of 24 frames per second, hence why it often looks jerky and over-cranked. Now the footage plays more smoothly, at the standard cinema frame rate we’re used to, giving the soldiers more lifelike movement.

How the footage was restored: Colour

Peter Jackson worked with historian Pete Connor to ensure historical accuracy at every stage. His input proved to be most invaluable during the colourisation phase. Connor provided Stereo D with detailed notes for each shot identifying each soldier’s rank, uniform colours, what each item should look like.

(Use the slider above to see the footage before and after restoration)

Jackson and his team also took photos from the real life locations to accurately match the colour palettes, and then the production turned to old school methods to achieve the desired effect. Every frame was then painstakingly rotoscoped, which is basically like hand painting every thing in shot, by tracing and isolating every element.

“I would describe the colour process as mostly forensic but also creative,” explains Adamou.

“On one hand we’re recreating a photo-real world, striving to provide an accurate interpretation of the environment and the people within it. Everything in the frame is dissected and analysed, then cross-referenced against records from multiple sources. From the unusually elusive colour of the British uniforms, to more obscure items such as a goatskin jerkin we see once in the movie, we painstakingly laboured over every detail.

“Then on the other hand we had some creative freedom to hone in on details that will be visually interesting to the audience. For instance, many of the soldiers wore private purchase shirts or other clothing, which we subsequently varied in colour to break up large areas of uniformity.”

How the footage was restored: 3D

3D is an unusual medium for documentary films, but Jackson felt it was essential on They Shall Not Grow Old to help immerse viewers into the world of these soldiers.

Led by Stereographer and Colour Compositing Supervisor Russell McCoy, the Stereo D team aimed to make viewers feel comfortable and immersed in the same 3D space where the original camera was standing.

“This film is a wholly unique application for 3D technology, and it raises the bar not just for the 3D medium but also for the documentary medium,” explained Mark Simone, Stereo D Producer.

“This project was different for us because the final product goes beyond entertainment or escapism, it’s the world’s history and with that comes a certain responsibility to the memory of those who lived it. Through this film, Peter is unearthing the past and presenting it to the public in a new and exciting way, which is something very special to be part of.”

The most difficult part of 2D-3D conversion is always the creation of footage that doesn’t exist. Foreground elements are extracted from background elements to create the depth needed, but this means VFX artists have to guess what appears behind the foreground elements, and create it from scratch.

However, with Stereo D’s proprietary software and team of over 400 artists, the process was streamlined. The same people who’d cleaned up the original footage, worked on the same reels of film, every step of the way right up to the 3D conversion.

“Certainly mastering the transformation and colorisation, especially at this scale, was new for us, but we had both the relevant expertise and the deep talent pool to handle it,” concludes Adamou.

“This was easily the largest and longest restoration project we have worked on,” adds Park Road Post Production’s general manager Dave Tingey.

“Due mainly to the amount of scanned footage and the post production processes employed to deliver the final look and sound for the film.This demonstrates that old footage can not only be restored, it can be enhanced and used in new ways to tell stories about our history.”

The newly restored footage has all been gifted back to the Imperial War Museum where it will be archived and used to educate future generations about the Great War for years to come.

They Shall Not Grow Old will receive its world premiere at the London Film Festival on 16 October, when it will also screen nationwide supported by a live Q&A with Peter Jackson.

For more information and tickets, please visit theyshallnotgrowold.film.

This story was originally published on 10 October, 2018.

Read more

First Lord of the Rings TV series details

Weinstein wanted to replace Jackson with Tarantino on LOTR

Bloom shares rare behind-the-scenes LOTR pic