True Story: A Former House Beautiful Editor Inspired the N95 Mask While Designing Bras

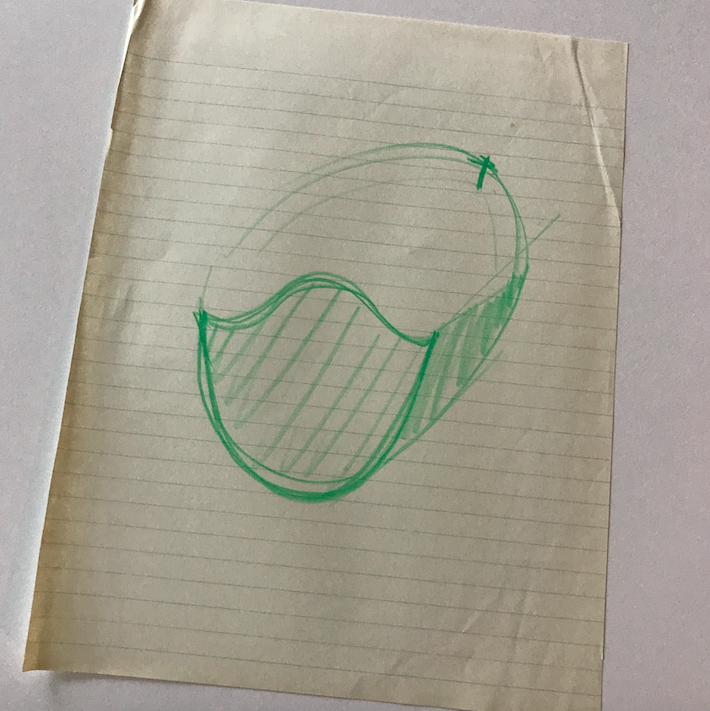

Although a few months ago the term "N95" might have meant nothing to you, by now you're likely quite familiar with the N95 mask, or respirator. According to the FDA, this close-fitting, bubble-shaped mask blocks at least 95 percent of very small airborne particles while still allowing free breath. It's a frontline worker's main armor against infectious viruses like COVID-19. But if you've ever looked at this remarkable piece of gear and thought it resembled a particular female undergarment (oh, don’t be embarrassed!), you’re not actually that far off.

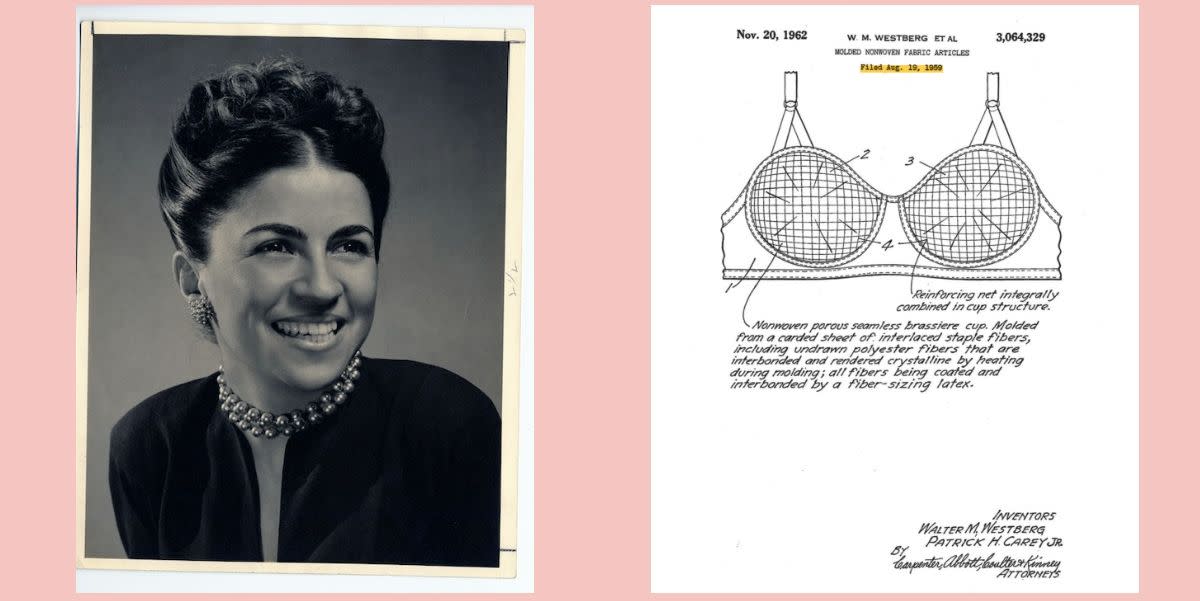

The first N95 prototype was inspired by a woman named Sara Little Turnbull, whose medical mask model stemmed from a prior design of hers—for a molded bra cup. The N95 mask, which was finalized in 1972, has yet to be one-upped. While Turnbull saw her mask used during 9/11, she wouldn't live to see her design save more lives than ever in 2020 (she passed away in 2015), she holds a special place in our hearts for a bevy of reasons. She was a design lover, a creative...and a former decor editor here at House Beautiful! But more importantly, she was a gutsy, strong-willed woman who wanted her voice (and ideas) to be heard. Last week, NPR's history podcast Throughline highlighted Turnbull’s life and her role what became the N95 respirator. Here’s her story.

Sara Little Turnbull (born Sara Finklestein) grew up in Brooklyn in the 1920s. "She was an extremely bright and very precocious child," said Paula Rees on NPR's Throughline. Rees, an urban space designer, was a friend of Turnbull and part of a team helped care for the designer up until her passing. Turnbull's inventive spirit paired with her passion for the arts made her a perfect fit at Parson's School of Design. After graduating, she began working at House Beautiful as the decor editor. Following a day of writing about luxury interiors, she'd go home to the 400-square-foot hotel room in midtown Manhattan that she was living in. "This was sort of her living experiment," Rees says. "She's very clever with her design ideas and had super organized storage so that you go into the space and everything was contained in the cabinetry."

Turnbull left House Beautiful with bigger ideas in mind, namely, forming her own company. The problem was that she was a woman in America in the 1950s. She penned an article titled "Forgetting The Little Woman," where she called out America's major manufacturers for only creating products for store buyers and not products that could be useful for the actual user. Turnbull, at 4' 11" was a bold, go-getting "little woman" who wanted to be heard.

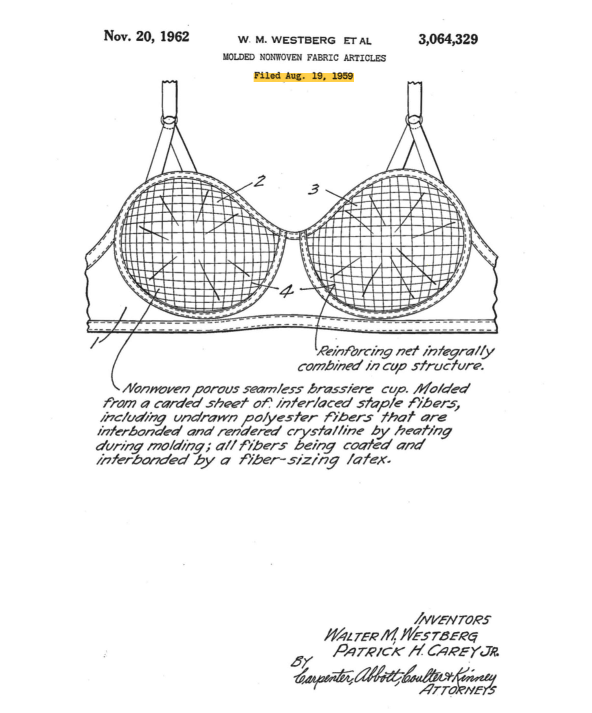

She caught the attention of American manufacturing conglomerate, 3M, where she was hired and assigned to the gift wrap and tape division. At the time, the company was experimenting with a new non-woven material that could retain all kinds of moldable shapes, allowing for the production of stiff ribbons. However, Turnbull saw far more potential for this material than just ribbon making. In 1958, she gave a presentation titled Why?—in front of a room of only men—where she presented her many ideas. Her pitch of a new product application using this new material gauged the interest of 3M. Turnbull was given the green light to create a molded bra cup.

At the same time, Turnbull was taking care of three of her immediate family members, each suffering from a different ailment. She had spent a substantial amount of time in medical environments and watched as doctors and nurses fiddled around with their flat, tie-on masks. She thought about her bra design, and how a cupped facial covering like that could be better for medical professionals — reiterating the foundations she had laid out in her article years before: corporations need to be designing products for end users (doctors and nurses), not distributors (the hospital). 3M liked her idea and in 1961 its first lightweight medical mask based on Turnbull’s molded bra cup design was released.

Initially, there were some problems. The mask couldn’t block pathogens, so 3M re-branded it as a "dust" mask. However, neither Turnbull nor 3M were putting the idea to rest. According to Fast Company, the Bureau of Mines and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health teamed up in the 1970s to create the first criteria for what they called "single use respirators." With these new guidelines introduced, 3M was able to produce the first single-use N95 “dust” respirator in 1972 — the same model we know today. Turnbull consulted on this line into the '80s, while also working with other corporate clients including General Mills, Ford, Corning, and Revlon.

The N95 respirator of course isn’t perfect. It can get uncomfortable when worn for long hours, and sometimes become difficult to breathe in. But while some scientists have been working to improve the respirator, Turnbull’s prototype lives on. What started as an idea to offer women extra comfort during their day-to-day activities prospered into a lifesaving device that still holds up almost five decades later. It's proof that good design can make a lasting impact.

Learn more about Turnbull's trailblazing work at the Sara Little Center for Design Research located inside the Tacoma Art Museum in Washington.

Follow House Beautiful on Instagram.

You Might Also Like