'The thirst and drive is there': a leap forward for British dance schools

‘One of the students created a lighting installation in a dishwasher,” says Lise Uytterhoeven, the director of dance studies at London Contemporary Dance School (LCDS). “From restriction you can get great creativity,” she says, laughing. Lockdown has stretched Uytterhoeven’s students’ imaginations, but of all the subjects you might try to teach online, dance must be one of the hardest: you need the bodies in the room, space to move and hands-on interaction. “We’re an absolutely in-your-face kind of art form,” says Janet Smith, who retired as principal of the Northern School of Contemporary Dance (NSCD) in Leeds in May, while the school was empty. “We all want to be in the room together, with close physical contact.”

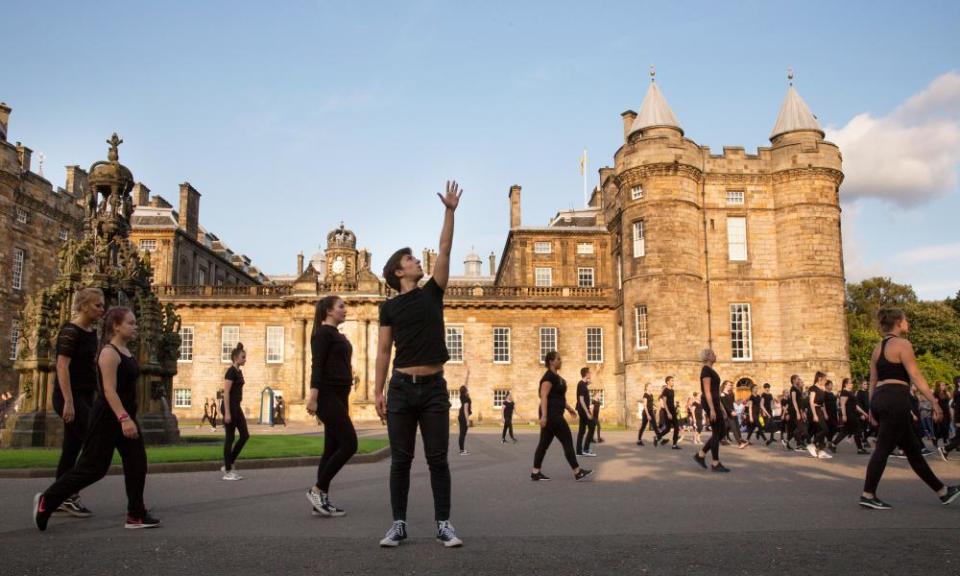

The leaders of the UK’s contemporary dance conservatoires swiftly adapted to the new normal, moving to online classes, auditions and now graduations – final-year performances from LCDS, NSCD and Trinity Laban in London can be seen online this month. Now they are planning for reopening in September, with a mix of online and studio teaching in socially distanced groups, plus experiments with outdoor classes.

There are questions overhead. One is about the kind of industry into which these dancers will be graduating and how much damage will be caused by the ramifications of coronavirus. Another concerns whether the lack of studio time will disadvantage a cohort of students going into a short, intense career where time is precious as it is.

It is five years since the leading choreographers Akram Khan, Hofesh Shechter and Lloyd Newson wrote an open letter stating that, in the highly competitive, international business of dance, UK-trained dancers were at a disadvantage, falling below the calibre of those from overseas. They lacked “rigour, technique and discipline”, said Khan; they were “outclassed by fitter, stronger and more versatile counterparts”, said Shechter.

At the time there was a robust response from training institutions – and almost a sense of betrayal. “It was upsetting, because we’re a small, interconnected community,” says Smith.

Has anything changed in the intervening five years? The question hinges on what we think we are training dancers for. In terms of the pursuit of technical excellence, the Juilliard School in New York is the “gold standard”, according to Amanda Britton, the principal of the Rambert School. But she points out that Juilliard takes 24 dancers from thousands of auditionees. “It would be very easy to train 24 dancers for the elite end of the profession,” she says.

UK schools have bigger classes, a much wider remit and a deliberately different mindset to some of their global counterparts. They offer accredited degrees and transferable skills to support the realistic picture that almost all dance graduates will have a portfolio career, in performing, teaching, choreography, community dance, administration and any number of other jobs. Uytterhoeven says that even before Covid-19, as a result of austerity and arts funding cuts, there were fewer stable jobs within dance companies. “We have a duty to prepare graduates to work in a wide range of roles. It would be irresponsible not to.”

All leaders of dance schools talk about inclusivity and want their students to represent a diverse range of dancers, backgrounds and styles. They recruit by potential, not achievement, noting that not everyone has access to high-quality training from a young age. “You risk losing such a range of artistic voices if you’re only starting with middle-class children who have done ballet since they were zero years old,” says Smith.

There are good reasons for not pushing all dancers into the same mould. Contemporary dance, by its nature, is always changing and responding to the world around it. It needs creators and thinkers, not just malleable bodies. “When I lived in America, they concentrated on physicality,” says Benoit Swan Pouffer, the director of Rambert dance company. “But you encounter dancers who have only the physical and it’s not enough. What differentiates one dancer from another is who they are and what story they have to tell. I’ve found British dancers have a lot of personality and a sense of self.”

In 2015, Khan’s producer, Farooq Chaudhry, spoke of British students being “mollycoddled”, but the teachers I speak to consider “kindness” part of their philosophy. The old-fashioned ballet cliche of teachers scaring their students into line has been consigned to the past. “We have to remember that there was a huge amount of students who left dance degrees never wanting to dance again,” says Darren Carr, the director of studies at NSCD. Smith adds: “Damaged, in fact.” “We’ve changed that culture,” says Carr.

Sara Matthews, the director of dance at Trinity Laban, says: “I deliver workshops around the world and I’ve seen different training methods. I’ve seen how the ‘whip approach’ actually creates a very passive learner and very underconfident young people.” Yet, quietly, some schools admit they have been working to boost the fitness of their students, an area seen as lacking – only these days the basis is dance science, using data and periodisation in training and building on the latest findings from elite sports.

All the school heads talk of evaluating and overhauling elements of the curriculum during their tenure. Has it made a difference? Akram Khan says that, from his efforts to engage with young dancers in recent years, “what is clear is that the thirst and drive is there, accompanied with potential and diverse physical facilities”. What he wants to impart are values – in his case, those of “curiosity, rigour, immersion and surrender”.

The dancer and choreographer Sam Coren says “dance is too insular in the way it trains”. “We spend so much of our time and attention on moving in a way which is physically not that relevant any more,” says Coren, who uses ideas from acting and clowning in his teaching. “Dance education doesn’t really prepare you for being on stage every night in front of an audience.”

Something must be working, because Shechter says he has started to notice a difference: “It’s something I can see in the auditions; there’s improvement all the time.” For Shechter, the problem is less with higher education and more with what comes before. “We don’t have early-age contemporary dance education in the UK, like they do in other countries. That’s the main reason it’s difficult to develop professional dancers in time,” he says. Dancing a couple of times a week after school and then training full-time at 18 will not prepare most students for the intense demands of professional dance, he says. (Rambert School takes students full-time at 16, while 12 Centres for Advanced Training offer more specialist training to limited numbers from the age of 10.) Shechter has worked with Amanda Britton on Rambert Grades, a contemporary dance syllabus that can be taught from the age of seven, which Britton hopes will help fill the gap left by the decline of GCSE dance.

Why does all this matter? Surely audiences just want to see great dance; it is unimportant where those dancers are trained. “It’s like arguments with my daughters about practising for their piano lessons,” says Shechter. “We can do it or not, I really don’t care, but if we do it, we do it really well. The point is: we’re doing it anyway; we should try to find a way to do it better.”

Trinity Laban’s student performances are online from 9 July. NSCD: Future Now runs from 14-16 July. LCDS: Cyber Rats runs from 17 July-17 August