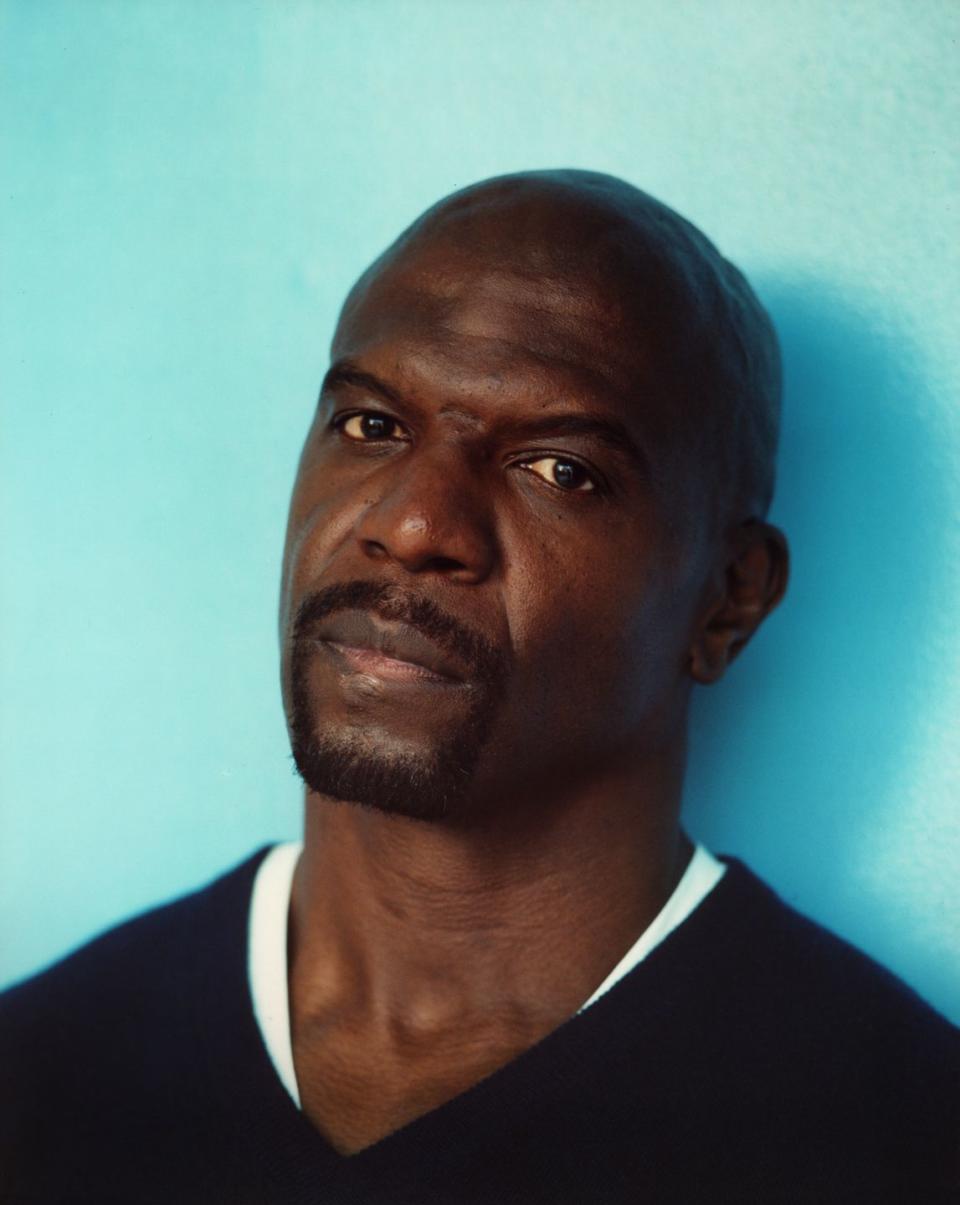

Terry Crews Is Fighting for the Young Man Within Him

On a late-summer day in Los Angeles, I plan to meet Terry Crews at the Getty Museum because, in addition to everything else Crews does-which, seriously, is everything-he’s a hugely talented visual artist. I figure we’ll go deep on the photography exhibit. I’ll ask: “Terry, what’s the inner monologue of the person in this picture?” Really get my Barbara Walters on.

What happens instead is that we get nine steps into the Getty Center, turn to one another, and talk for five solid hours-about toxic masculinity, sexual assault, and the power structure in Hollywood. He’s candid throughout, even as a ring of tourists forms around us, very possibly wondering whether they’ve wandered into a Terry Crews TED Talk. One by one, people give a look, and then another, and then a full, delighted stare. “I always say I have a superpower,” he tells me. “My superpower is that I’m unembarrassable.”

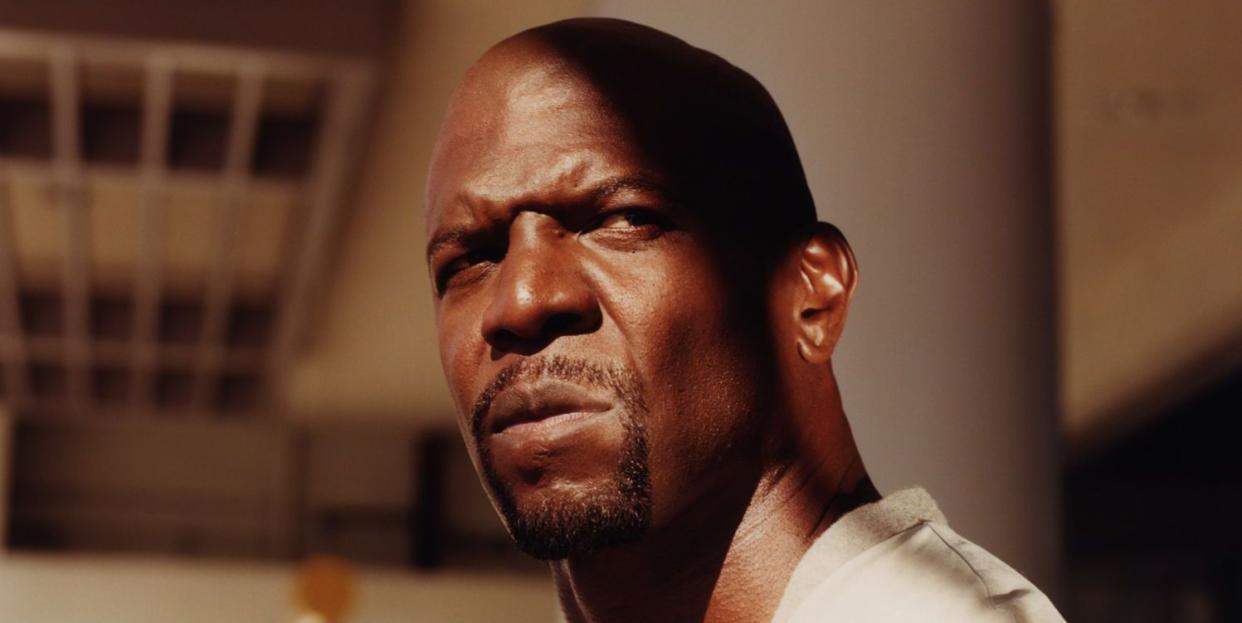

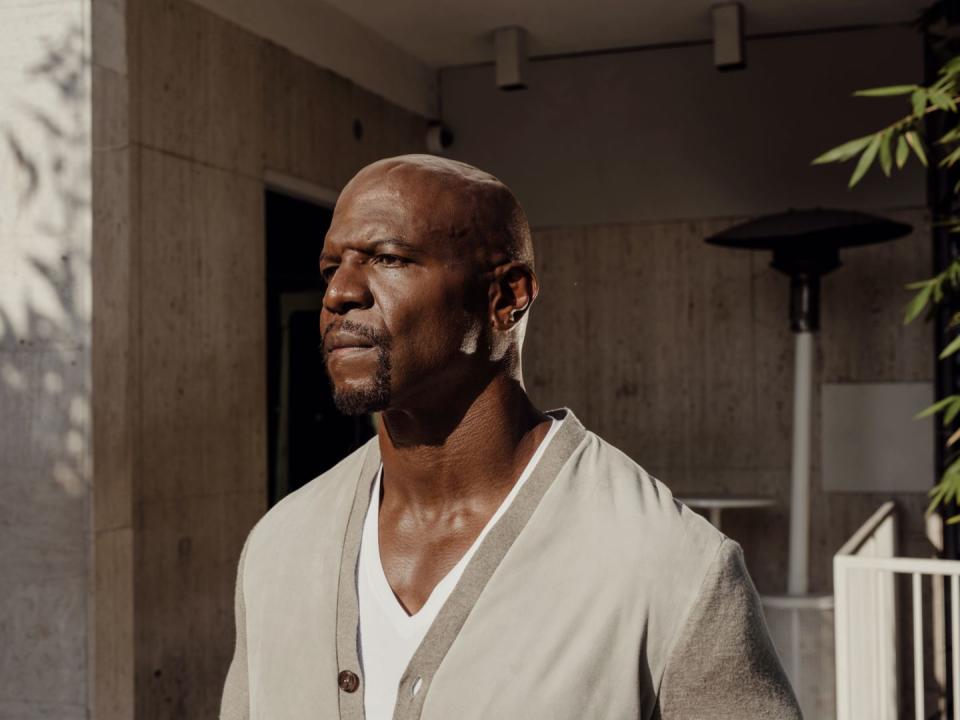

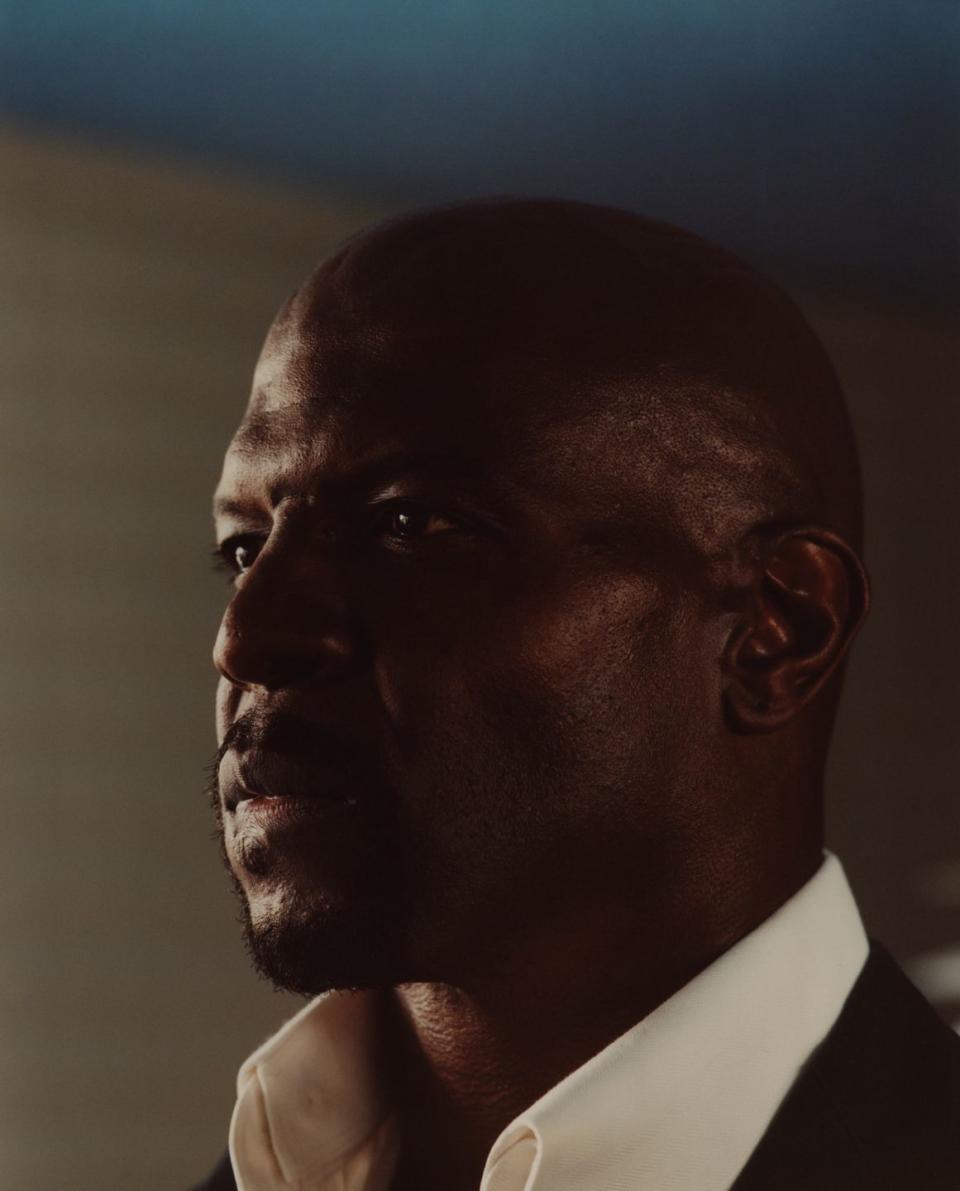

Crews carries himself with a certain military precision. He arrives at the Getty Museum at twelve o’clock noon and zero seconds. He looks me dead in the eye and shakes my hand intensely and firmly, but not too much of either. He stands with his shoulders back and chest out, as though he might salute at any moment. He wears a crisp cream polo shirt with matching jeans and sneakers-almost a uniform.

All of this makes sense because, right now, he’s on a mission. Terry Crews is using his fame, his brains, and his boundless energy to completely redefine masculinity for the twenty-first century. He’s gone public with his recovery from pornography addiction, with his experience of life with an abusive father, and now with his own sexual assault. He has consistently challenged himself, pushed past what’s expected of an athlete, an actor, a man. Now he's challenging us to change the way we see ourselves and our role in the world. “There’s a whole lot of rebuilding that needs to happen,” he tells me. “So it’s gonna be messy.”

Sweater by Barneys New York.

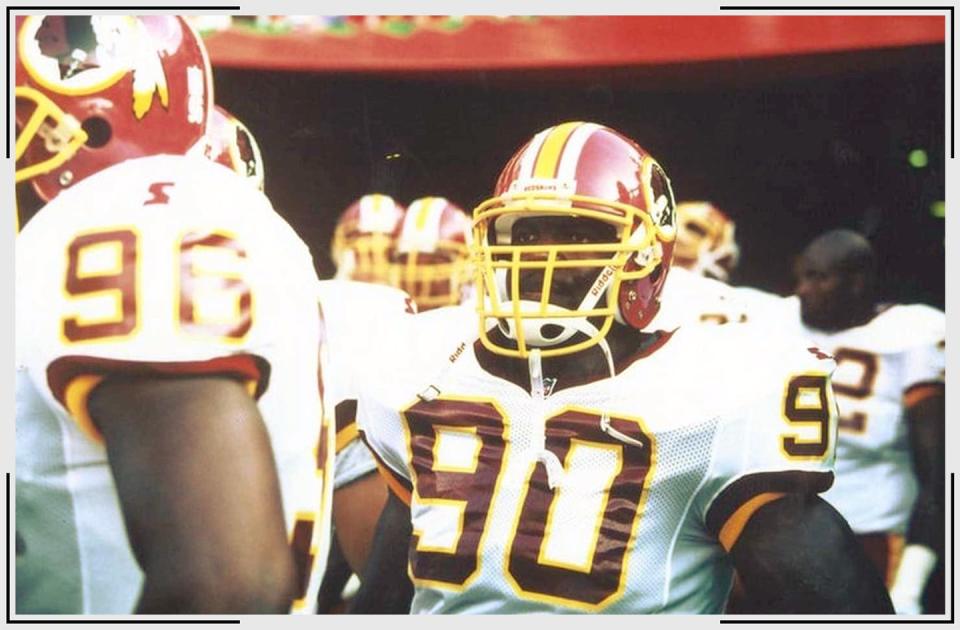

The man definitely has a record of fearlessness. He famously got his start in the NFL, doing stints with the Rams, the Chargers, and a team whose name we don’t say anymore, before heading to NFL Europe to play for the Rhein Fire. From there, he did a couple of seasons as T-Money on the nineties American Gladiators clone Battle Dome (the Rollercage was his specialty). And then, like very few NFL journeymen and roughly zero other Battle Dome warriors, he launched himself into movies.

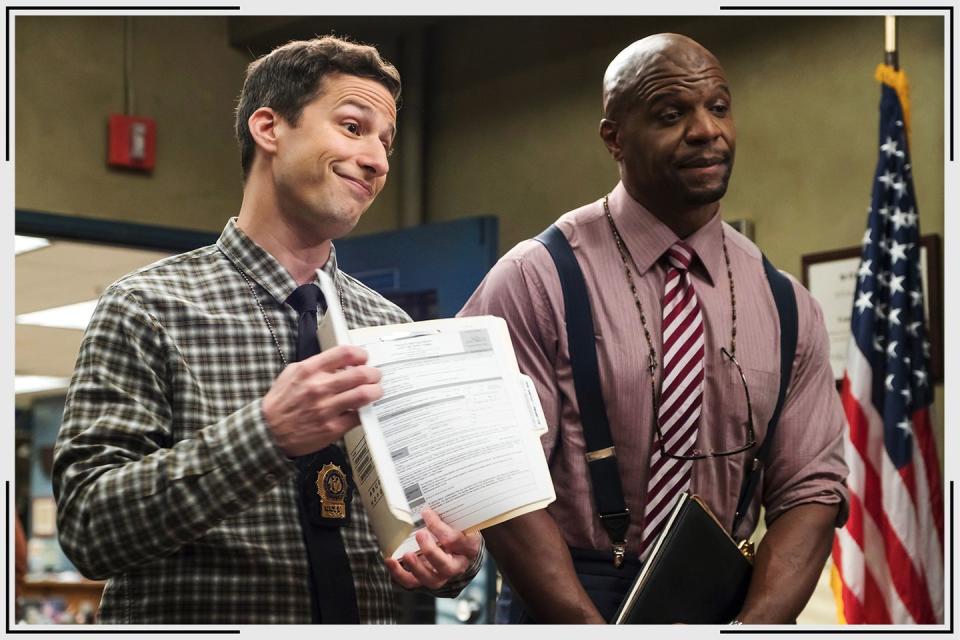

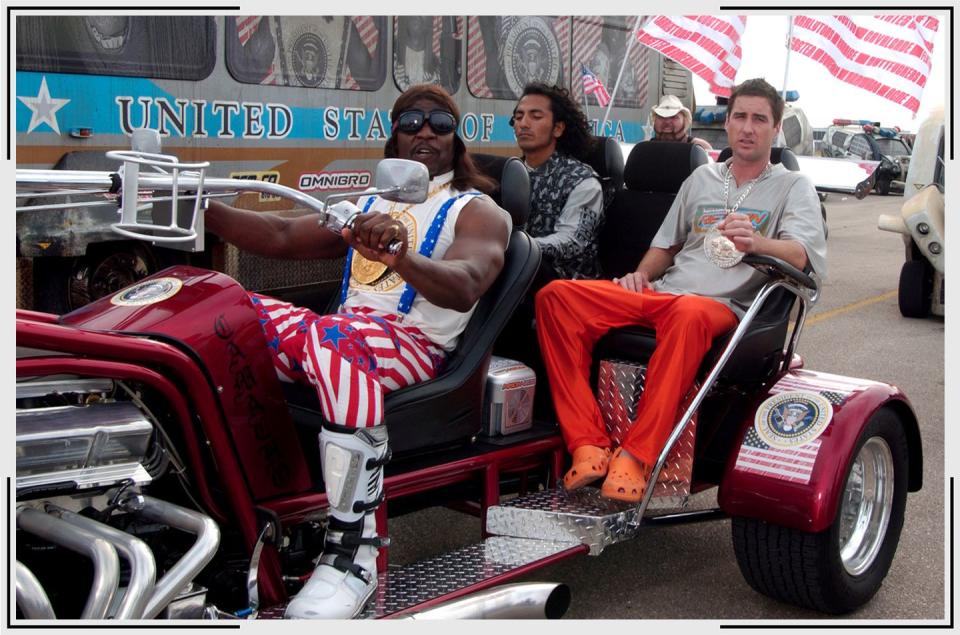

“There’s an unspoken rule in comedy,” he says an early castmate told him, “‘Muscles are never funny.’” Crews didn’t listen. Since then, he’s played President Camacho in the hilarious, depressingly prescient 2006 Mike Judge film Idiocracy, Chris Rock’s dad in Everybody Loves Chris, and, most recently, “Little” Terry Jeffords on what we can now call NBC’s Brooklyn Nine-Nine. He’s been the Old Spice Guy and the host of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? He’s had a career marked by boldness, and he insists it's just getting started: “I've reached fifty, and there’s a wonderful period where people who are older just do not care what you think anymore.”

If Terry Crews ever had a comfort zone, its walls are in ruins.

Crews had wanted to start the day in the exhibit of ancient Egyptian antiquities because of one of his other enterprises: his contemporary furniture line. Designed and released by the actor, the Terry Crews Collection is based on one notion: What if Egyptian culture were still dominant? “It was very important to me to take a non-European view. When you look at Mongolian culture,” he tells me, “everything is in a circle. If that was the number-one culture, our homes would be round.” Crews’s high-end collection takes its cues from the Egyptian furnishings that are ten feet away from us at the Getty Museum-artifacts that we are aggressively not looking at.

Good design is a constant in his life. On the set of Brooklyn Nine-Nine-the show Fox canceled earlier this year and NBC picked up the very next afternoon-he worked with a decorator and redid his entire backlot-bland dressing room. “It’s like an optical illusion now,” his former costar Chelsea Peretti laughs. “I walk in and his room looks like it’s ten times bigger than mine. And in Italy.”

I would say that talk of design lights up Terry Crews, but Terry Crews is perma-lit. The story of his first collection is a roundabout journey, fueled by his eagerness to learn. “I’ve always been a student. I had to know why this house was better than that house, why an Eames chair is better than Ethan Allen furniture.” After sponsoring the first furniture collection of Nigerian-American designer Ini Archibong, Crews met Jerry Helling, the president and creative director of Bernhardt Design-“literally the best American company; on par with the Italians. He said, ‘I want to do something with you.’ I said: ‘Okay, we'll find Ini. We'll do it again.’” But the creative director had done his research and knew Crews himself was a design force in the making. “He was like: ‘I want your ideas.’” His face does whatever one would call the next level up from beaming. “I was like, ‘Oh shit. What do I do now?’”

What he did then was spend six months sketching his Egyptian furniture fantasy, which became the Terry Crews Collection and later debuted at the high-end International Contemporary Furniture Fair in 2016. The collection includes couches that evoke the ibis, the bird that adorns many of the artifacts in this Egyptian exhibition, which, again, we are not even pretending to look at. He shows me a picture of his ibis sofa, which is beautiful. It’s sleek and sophisticated, and I hear myself say out loud, “Jesus!” It is the only moment all day when Crews’s light dims ever so slightly, and I feel a level of shame I haven’t felt since I had regular access to nuns. Do not take the Lord’s name in vain around Terry Crews, I think to myself. Noted.

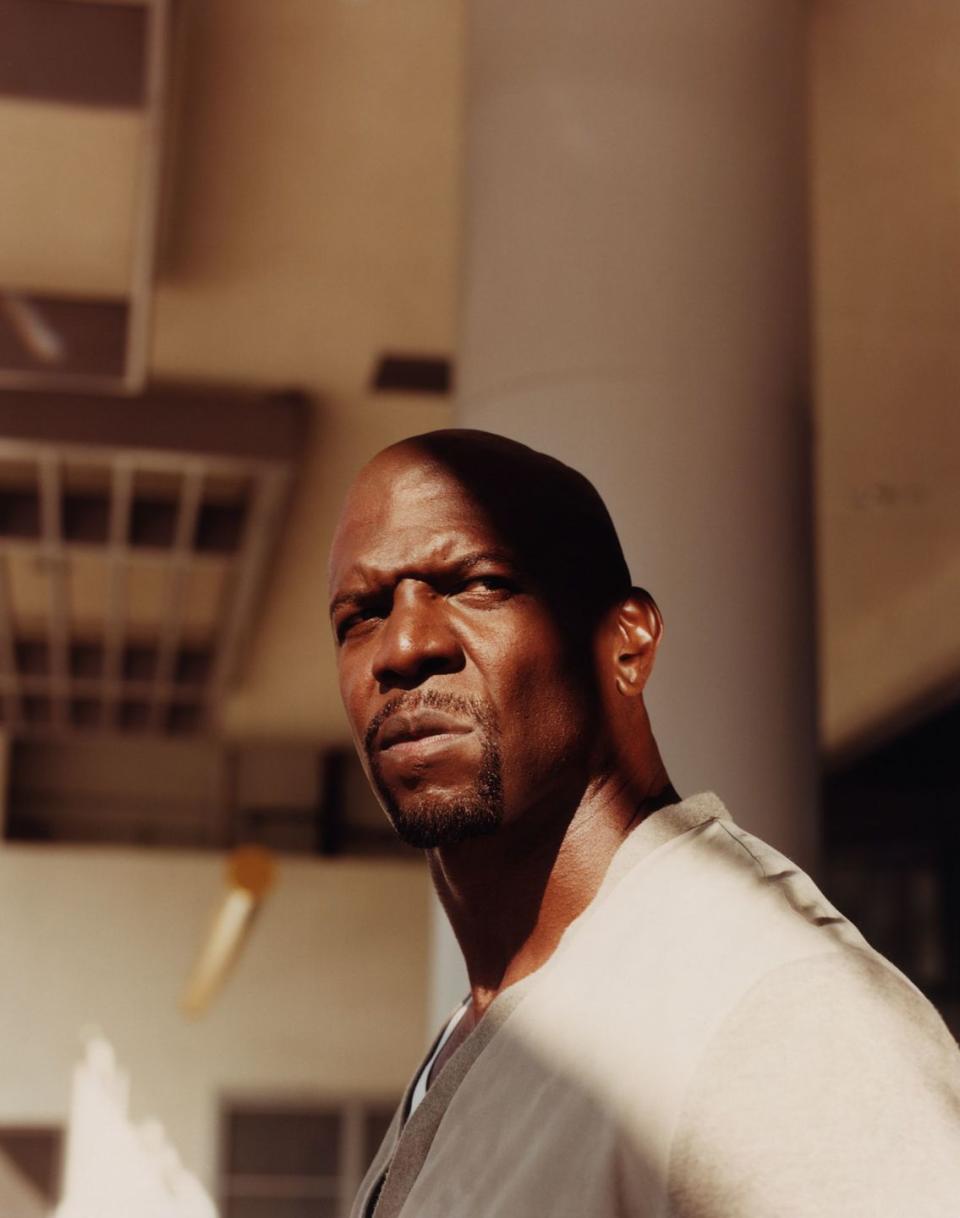

Denim blazer, shirt, trousers, and boots by Nana Boateng for Amen & Amen; watch by Tag Heuer.

“Some people find creativity in self-exploration,” Crews’s Brooklyn Nine-Nine castmate Joe Lo Truglio tells me, “but they don't have the motivation to do anything about it. Others have an incredible work ethic but nothing to say. Terry's rare. Terry has both.”

He’s a lifelong athlete, so the physical energy is not a problem. He swears by intermittent fasting; he only eats between 2 and 10 p.m. each day. “When you have food in you, your body concentrates everything on breaking it down. It’s like, ‘Let’s get on this food.’ But when you have nothing in you, it's like, ‘All right, we've got nothing to do. Let's get on his eyesight. Let's work on the tendinitis in his knee. Let's work on his skin.’” (Having spent several hours in close proximity to Terry Crews’s skin, I can reveal that I now also swear by intermittent fasting.)

But where does the creative energy come from? How does a person, especially a person with as high a profile as Terry Crews, find the nerve to take such a risk? It’s in that inability to be embarrassed. “When you’re twenty-five, you're always wondering why you're not accepted. You're fighting all this time to get accepted, and then when you stop, that's when they accept you. When you start realizing you can just be you, all of a sudden you're amazing.”

The ring of museum-goers that has remained around us agrees that he is amazing. Here’s what happens when you are standing and talking with Terry Crews, in the middle of an actual museum where people go to look at art and antiquities: People will look at him. This is Los Angeles, so the crowd is primed to see celebrities. They will stop and gawk and whip those smartphones out for a furtive picture. But what they don’t do, almost at all, is approach him, at least not here. He is so on fire, so clearly passionate about what he’s discussing, people individually come to the same conclusion that it’s best not to disturb him. He has a strong aura, and people stay reverently on the other side of it.

Which is what makes what happened to him, the incident that provoked this phase of his mission, that much more surprising.

At a party in February 2016, Adam Venit, then the head of William Morris Endeavor’s motion picture division, introduced himself to Terry Crews and Crews’s wife, Rebecca. Crews sensed that something was wrong with him. “I grew up around drinking,” he says. “This wasn’t drunk, but it was something.” When Venit approached, Crews put himself between him and his wife.

Then Venit put his hand on Crews’s penis and testicles, and squeezed. “He just grabbed my stuff,” Crews says.

Crews didn’t react in the moment, thinking maybe Venit would realize he was grabbing someone’s genitals in the middle of a crowded talent-agency party, because, oh boy, that’s how you begin to rationalize sexual assault in the moment when it’s actually happening to you. In Crews’s telling, just then, Venit moved into another state of consciousness. "My God, he cackled as if it was the funniest thing in the whole world. And it was like he wasn't high anymore.”

In the past, Crews would have gone with his reflex and done the thing our culture tells boys to do when someone is making them angry: beat the hell out of him. But he doesn’t do that anymore. “My wife has seen people get tossed over her head at the club. But back home, she would say, ‘Never do this again.’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah, but he deserved it,’ and she’d say, ‘Listen to me: You cannot do this. You will lose everything you have. Or they’ll put you in jail, or they’ll shoot you.’”

This night, at a party with some of the most powerful talent agents in one room, and the hand of one of the biggest big shots right on his dick, Terry took Rebecca’s words to heart. He didn’t push back because he couldn’t push back. “Everyone would be screaming and running, and it would be a horrible scene. And then everyone in that room could make a phone call to every movie studio in the world: ‘Well, you know about Terry,’ and they’d believe them. [Pushing back] is not an option. It just isn’t. I got too much to lose.”

“This is what toxic masculinity is,” he continues. “People think, ‘Look how big you are, look how strong you are. If I was you I would've killed him.’ But my body's not for killing. In America, we want to finish the movie. And the movie if you’re a man is Dirty Harry.”

I nod, as do a few members of the assembled crowd, collectively ignoring the home furnishings of ancient Thebes.

“Can you imagine if I’d have hit him? Can you imagine if I broke his eye socket? Would anybody have believed me? He could've said, ‘I just bumped into the guy and he walloped me in the eye.’ And everyone would have looked at him, looked at me, and been like, ‘That makes sense.’”

At the party, Rebecca whispered in his ear: “I’m going to go to the car.” He said his goodbyes and followed. “She said, ‘Okay, that’s good. You handled that correctly.’”

“It saved my whole existence.” Terry shakes his head. “And I’m like: ‘I’m such a bitch.’”

It is that moment of cognitive dissonance, in having chosen to deescalate a public sexual assault, and in leaving the room feeling like the weaker man, that makes him want to speak up.

For some time now, Terry Crews has been one of the more public critics of what we’re calling “toxic masculinity.” His 2014 book, Manhood, opens with a story about seeing Iron Man 3 with his then-seven-year-old son, Isaiah. Iron Man 3 is a pretty violent movie, particularly if you’re seven and you’re new to movies on big screens. Isaiah recoiled from the louder and more aggressive scenes, and Crews asked if he was scared. Isaiah said, “No.” In that moment, Crews saw how early, and how thoroughly, the rules of masculinity imprint themselves on us: Don’t be afraid. Don’t be a victim. Don’t need help.

He brings up the Friedrich Nietzsche quote about insanity-“In individuals, insanity is rare; but in groups, parties, nations, and epochs, it is the rule”-when he talks about the elements of traditional masculinity that are eating away at us. And he has a point: It is insane that someone can sexually assault a client and get no harsher an initial punishment than a demotion and a thirty-day suspension.

A few days later, Crews told Ari Emanuel, co–chief executive of William Morris Endeavor, about the incident. “I was assaulted,” he made clear. “We're not talking harassment.” According to Crews, Emanuel promised that Venit “would lose a lot of money in thirty days,” and then asked him: “Would that be enough for you?” Crews’s face, more than two years removed from the incident, makes clear it was not.

The insanity plays out in ways obvious and more subtle. “I play the flute,” he tells me. “I love to play the flute. I did an interview with Charlamagne tha God, and we were talking about code-switching, which we deal with in [this summer’s Sorry to Bother You]. And I said, 'I've always dealt with being an athlete and an artist and how people want me to join sides.' And I said, ‘You know, I play the flute.’ And everyone cracked up. They laughed. I said, 'I'm being serious.'

"And you know what Charlamagne said? He said, ‘Your ass is too big to play the flute.’ That's what that masculinity is. You don't fit what I'm saying you should fit, so you’re done.” He shakes his head in disbelief.

He’s been a participant in the collective psychosis of masculinity, and he knows it. “I was in the NFL. I was a card-carrying member, because you don't want to be kicked out. So I'm like, ‘Yeah, man, look at that ass!’ Even if I might not have felt that way. Did I rape anyone? No. But did I look the other way? Hell yes. While all those things were going on, I didn't say anything. Because what are they going to do to me-will I be excommunicated?” The religious language is no mistake: “It’s a cult. You don't go along with what everybody's saying, all of a sudden you're out. That's hard.”

If toxic masculinity is a cult, Crews wants to be its deprogrammer. “The story we tell ourselves is, if you’re a man, you can’t be assaulted. So what happens when it happens? Are you not a man?” Crews tells me a story from his football days, a true tale he used to hear in locker room pep talks: A player hurts his finger, the medic tells him he’ll need to miss a game if he takes the time to let it heal properly. Instead, the player tells the medic to cut it off. “And that story is told all the time in football circles as stick-to-itiveness, confidence, and extreme toughness.”

He laughs. “Now, I’m gonna tell you, that guy wants his finger back.”

His first public appearance after having come forward about the assault was intense: “Just coming out of the car, everybody's looking at me like: You're that guy. I call myself unembarrassable, but there it was.” For speaking out, he’s been publicly mocked by the likes of 50 Cent, who Instagrammed a meme of a topless Terry, carrying the text: “I got raped, my wife just watched.” But Crews dealt with it. “When he went off and did his joke about me, I had to realize that I would've felt the same way. I can't really be defensive or be mad because when you don't know, that's actually the first go-to.” There is no time for beef on this mission.

Earlier this year, Crews testified before the Senate for the ratification of the Survivors’ Bill of Rights Act. In his opening statement, he shared his personal story of having grown up with an abusive father and the misconceptions about manhood it instilled in him. “As a man, I was taught my entire life that I must control the world.” According to Crews, that’s why men sometimes wait decades before reporting. We’re so afraid of being victims, in a judicial system that is still dominated by our gender, we make it impossible for ourselves-not to mention women and other marginalized genders-to get justice.

Crews didn’t wait. He brought a suit against WME and Adam Venit. In his complaint, he said, “…[A] message needs to be sent to those in power who abuse those over whom they can exert influence and control that abuse and sexual predatory behavior will not be tolerated.”

He’d received an apology from both, but apologies have never been enough for him. “My dad would beat my mom,” he tells me, “and he would always come back, super apologetic. It'd be tears or flowers or candy. And then it would happen again.” For him, forgiveness isn’t the point-it’s about accountability. “I'm not going to accept an apology until there's actual repercussions. It’s like you’re driving drunk, and you hit someone and say you're sorry. And then you get right back in your car and drive away. Is that a real apology?”

The goal now is to dismantle what he calls the “complicit system” that surrounds sexual assault in America. If a rich and famous person gets molested in front of people, with witnesses, and nothing happens to the molester, what hope for fair treatment does the average person have? “I am feeling vigilant for those who are still fighting. Halfway into the suit, I’d spent almost four hundred thousand dollars. How can a normal person do this? I spent the equivalent of a house.” The expense, and the shame of branding oneself a victim, keeps the complicit cycle spinning. “So, abusers will be like: ‘Well, look, my son had a good time. He fingered a girl behind a dumpster, but he didn't kill her. Why would you ruin his life?’”

“You can't treat me that way. No man, woman, or child can be treated this way, ever. I got zero tolerance.”

Sweater by Ralph Lauren Purple Label; T-shirt by Hanro.

I

think about something Terry told me earlier in the day about his furniture collection: “Design is about simplifying things that seem really complex. You’re taking images, shaving them down, forming them up, so you can understand them.” What he’s telling us, right now, in speaking out as a victim-that traditional masculinity is killing us, it allows abuse to go unpunished, and all genders deserve better-is so simple, but it’s made complicated by people who benefit from the status quo. Dismantling that system is his mission.

So far, Terry Crews has been effective at his mission. On September 10, Adam Venit announced his retirement from William Morris Endeavor. Later that week, Crews tweeted a scan of Venit’s apology and added, “Apology accepted WITH HIS RESIGNATION.” And Crews wants to make it absolutely clear: Venit’s retirement is the direct consequence of his actions. “They phrase it as a retirement and separate it from my case. I know how the game is played. The fact that he did this, and now they cannot employ him in any capacity from here on out, is a win for me. And a win for Hollywood."

@WME ‘s ADAM VENIT FULL APOLOGY LETTER:

Received: March 22nd, 2018

Accepted WITH HIS RESIGNATION: September 10th, 2018#Accountability

Read in full below: pic.twitter.com/Hbe4tu7UPL- terry crews (@terrycrews) September 14, 2018

Crews is using his resources-his profile, his money, his reputation-to fight the system in a way the average victim cannot, and he’s doing it for them, but also for himself: “See, there's a little boy inside Terry Crews. He was molested. If I don't stand up for him, who will? Every person on Earth is still that kid. You're still that kid. There are a lot of people who’ve cheered me on since then. It’s been a victory for a lot of people who could not speak.”

This specific phase of Terry Crews’s mission is over now. “This whole past year has been like an episode of Black Mirror,” he says. “And now I’m standing in the end credits. So much brain space, so much energy went to this. I just told my manager, ‘I need three more jobs.’” And in the time since I began writing this profile, it was announced that Crews will host NBC’s America’s Got Talent: The Champions, starting in January. Terry Crews is, in fact, never going to stop.

Photography by Carlos Chavarria • Grooming by Olivia Fischa for Celestine Agency using Kiehl’s • Designer & Stylist: Nana Boateng • Shot at The Standard Hollywood & Croft Alley at The Standard

('You Might Also Like',)