Are slogan hats the new slogan T-shirts?

Spotting a man wearing a baseball cap that featured only the name Rachel Cusk, the British author beloved of LRB subscribers, stopped me mid-scroll. A cultural commentator I follow had posted a selfie to his Instagram feed saying: “Copped the hottest hat.”

He is not alone in saying something with his headgear. Vogue editor Edward Enninful recently posted a picture of himself wearing a baseball cap sporting the name “Kloss”, not a reference to the supermodel Karlie but to a fashion film production company, owned by his partner Alec Maxwell. This week saw the arrival of merch promoting the latest book from Sally Rooney – a bucket hat with its title, Beautiful World, Where Are You, embroidered in black against a yellow background. Upper East Side institution The Carlyle hotel, a favourite of Jackie Kennedy and Sofia Coppola, recently teamed up with FRAME on baseball caps sporting its luxe logo. Last year, Timothée Chalamet was spotted wearing a baseball cap embroidered with “Elara”, the indie film production company responsible for instant cult classic Uncut Gems.

While there are of course still many bucket and baseball caps that say either nothing or nothing beyond a big fashion brand name, it seems that others are using them as they might once have worn a slogan T-shirt: to express something about themselves to the world.

It comes at a time when all kinds of hats are big – the visor is a bestseller in the Victoria Beckham Reebok line right now, Hailey Bieber’s head seems to see the sun only rarely, and, in line with the Y2k resurgence, trucker – and especially Von Dutch – caps are being worn by people who would need to Google the millennium bug. On the catwalks, high fashion names such as Celine, Isabel Marant and Balenciaga have embraced baseball caps, and Vogue has even re-branded “hot girl summer” as “hat girl summer”.

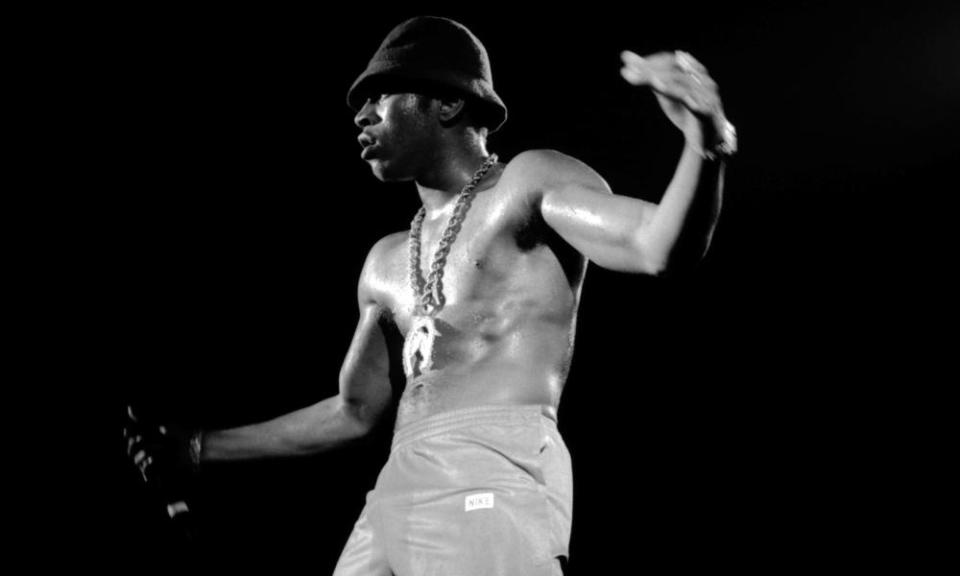

For many, the baseball cap has never gone away. Spike Lee, for one, has been wearing a New York Yankees cap since the 90s. Ditto the bucket hat, which has been popular through the years with hip-hop artists like Run DMC and LL Cool J as well, later, as with the Madchester and Britpop crowds.

It has been a few years since the statement T-shirt went mainstream – in 2017, Dior’s “We Should All Be Feminists” T-shirt, a quote from the writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, became the most Instagrammed look of the spring/summer Paris fashion week. The following year there was an exhibition dedicated to statement tees at London’s Fashion and Textile Museum. As curator Dennis Nothdruft put it at the time: “The T-shirt has taken on a role as a signifier, a statement of intent for the wearer. It has developed an amazing power to communicate and to create a dialogue between the wearer and the world.”

So now the hat. According to John Lingan writing in the Smithsonian magazine, it was in 1901 that the baseball cap went from sunshade to “battle flag” when the Detroit Tigers put their namesake animal on their caps. “The cap’s usefulness and brandability would turn it into perhaps America’s greatest fashion export,” writes Lingan, “changing the way people dress in every country of the world.”

In the past, baseball caps often symbolised relatability. As Lingan argues: “Atop the head of Princess Diana … [they] helped nurture her reputation as the ‘people’s princess’”, while “rumpled, unbranded caps” on the likes of composer Steve Reich and Paul Simon signalled “no stuffy art-world or rock-star glamour here … These are millionaires you could have a beer with.”

Now, however, hats are being used to make more specific statements about favourite authors, shops, hotels and film production companies.

Baseball caps are also being worn in ways less about relatability – see the Cornell college baseball cap worn in one of the summer’s most talked-about shows, The White Lotus. It was chosen to encapsulate the “doucheyness” of Shane Patton, the character who wore it; the ultimate symbol of his Waspiness. See also the caps of the billionaire Roy family of Succession, worn in seasons one and two, and spotted in the trailer for this autumn’s season three. They might be unbranded, but they are certainly not rumpled; their optics are most definitely not by-the-by. As the New Yorker’s Rachel Syme put it, these “logo-less wool baseball caps with perfectly curved bills” fit within the “sea of neutral tones” that are “subtle codes of class and power” in a world where, she says, the strictures of “extreme wealth” and “vanilla taste” mean that “one misplaced move can out you as an interloper or a fraud”.

Hats are also the perfect accessory for the Zoom age – statements of who we are that are visible on small screens in the same way as bookshelves, posters and house plants, which have all become sites of identity-signalling on calls with friends and colleagues this year like never before.

Not only does a hat make a great billboard for whatever is explicitly being advertised, it is also, in the same vein as statement tees, a communication tool between wearer and world. Hats can be a conspicuous way to signal belonging, at a time when belonging has been challenged by stay-at-home orders – even if that belonging is not to an international baseball team but a much smaller group of people who rate Rachel Cusk for her sad themes and steely prose.