Sir Robert Cohan obituary

Sir Robert Cohan, who has died aged 95, transformed the dance scene in Britain in the 1960s. A charismatic dancer, notable choreographer, great teacher and artistic director, Cohan was the man who gave form to the vision of the philanthropist Robin Howard that American modern dance could take root and flourish in the UK.

Howard, an admirer of the US dancer and choreographer Martha Graham, established the Contemporary Ballet Trust (which became the Contemporary Dance Trust) and found a home for a contemporary dance school at The Place, London. He gave Cohan the mission of forming a company, and London Contemporary Dance Theatre (LCDT) was born in 1967.

Cohan, a dancer with the Martha Graham Company, had been teaching at the Graham School in New York since 1948 and already had an impressive list of teaching credits when Howard invited him to London. He had the ability to analyse movement and introduced both a gravitas and playfulness to his classes while encouraging dancers to accept that discipline and hard work were vital.

His classes were Graham-based, but he appreciated that British dancers were temperamentally different from Americans, so the technique evolved somewhat differently. His approach was showcased in the dance piece Class (1975), which choreographed a class in progress. Cohan simplified Graham’s technique, emphasising that all movement originated from the centre of the lower back.

After his first few years as artistic director of LCDT, Cohan decided that all the works the company performed should be specifically created for his dancers. The rich legacy of his encouragement may be seen in the work of those who emerged from LCDT, among them the choreographers Richard Alston, Siobhan Davies, Robert North, Anthony van Laast and Darshan Singh Bhuller, and the dance leaders Kenneth Tharp and Isabel Tamen.

When, owing to a lack of Arts Council funding, LCDT folded in 1994, the company’s dancers recorded that “Bob has moulded, inspired and guided generations of dancers and is the person above all others responsible for the legacy of excellence long-associated with this company. Few men can command such respect so effortlessly, and indeed if there is a testimonial to his achievement it’s in the enormous commitment he engendered from his dancers.”

Cohan remained involved with the Contemporary Dance Trust until his 90s, latterly as a valued member of its board.

Born in New York, Robert was one of the three children of Billie (nee Osheyack), who worked for the US postal service, and Walter Cohan, a printer, and grew up in Brooklyn, his interest in the arts and nature encouraged by his parents. He made his first appearance on stage aged seven or eight in his own tap dance to Way Down Upon the Swanee River. During the second world war, he was assigned to the US Army Specialized Training Program and posted to Britain.

While in London he saw the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in Robert Helpmann’s dramatic and symbolic Miracle in the Gorbals, which encouraged him to recognise the possibilities and power of dance. On demob, he began training at the Graham School in 1946 and within a few months was dancing with Martha Graham’s company. He began to create dance works in the early 1950s, with his solo Perchance to Dream for the American Dance Festival, Connecticut College.

Cohan performed with Graham until 1969, as one of a group of virile male dancers supporting their star. The nature of working with a leading American dance company was employment for blocks of time: for seasons in New York, national and international tours. He also performed in the Broadway musicals Shangri-La and Can-Can (both 1956), and for a season in 1957 worked in cabaret in the Caribbean with the dancer and choreographer Jack Cole.

This work enabled him to fund his own choreographic ventures and eventually in 1962 to create his own small company. From 1961 until 1965, he directed the dance department of the New England Conservatory of Music, combining teaching with performing and choreography. Most of his early works were solos or duets with Matt Turney, many to scores by Eugene Lester, but from 1964, when he created his first work for the Batsheva company in Israel, his choreography was being seen internationally.

He continued to dance until 1972, adding the weight of a seasoned artist to the novice LCDT, and as a choreographer he never stopped working – last year he created a series of solos for Yolande Yorke-Edgell’s Yorke Dance Project.

Soon after Cohan arrived in Britain in 1967, Howard presented the LCDT’s first performances, of Dance, One, Two. Four, at the new Adeline Genee theatre in East Grinstead, away from the pressure of London – although most leading dance critics ventured to Sussex for it. The programme was tactfully presented by Cohan, who included Graham-trained guests to improve its professionalism and cleverly produced the students to disguise any initial weakness. After two years during which he commuted between New York and London, Cohan recognised that he had his work cut out – whenever he left London, work stopped, and he was needed permanently at The Place.

Possibly his most important creation for LCDT was his powerful Cell (1969), a three-part work for six dancers trapped in a non-specific situation; a dance of drama which would resonate powerfully for audiences in eastern Europe as well as in the west. With Cell, Cohan moved away from abstraction and introduced a more human element, albeit the dance concerned man’s destructive nature. Created during a period in which the war in Vietnam was being fought and concern about the nuclear bomb evident, Cohan worked with six hand-picked dancers and the composer Ronald Lloyd’s “angry” music concrète to create his breakthrough work.

Its success reassured Howard that he had found the ideal choreographer/artistic director and its longevity was such that it appeared still relevant and powerful when presented on the company’s closing programme at the Marlowe theatre, Canterbury, in 1994.

Cell was televised effectively by Bob Lockyer for the BBC in 1982. Lockyer’s film recordings of the 1970s and 80s provide a superb record from a time before company recordings were of the broadcast standard reached today. Cohan was involved with film and television from early in his career, dancing in A Dancer’s World, about the Martha Graham Company, in 1956 and choreographing Dido and Aeneas for the Boston TV company WGBH-TV in 1961. His understanding of the medium enabled him both to create original works for the screen and to adapt stage works to achieve on screen the effect created in live performances

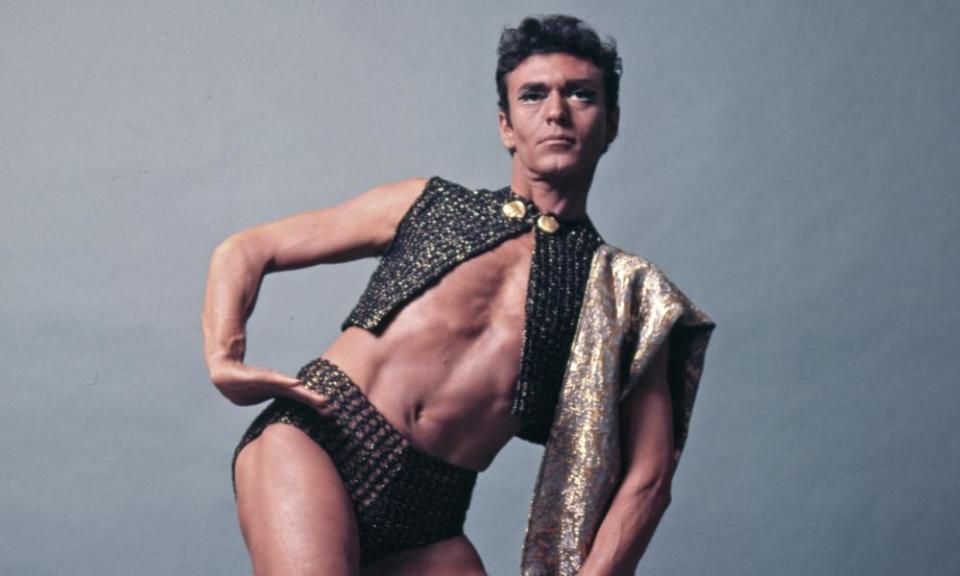

With his long hair, trendy outfits and platform shoes, Cohan was very much in tune with the wider world of the 1960s and 70s and The Place became a stimulating centre of creativity. His productions tapped into contemporary life and responded to theatrical demands. At times he was the heir to Graham in reinterpreting myths for a contemporary society. Stages (1971) was a stunning multimedia, full-evening presentation of a hero’s spiritual journey to self-awareness, designed by Norberto Chiesa and Peter Farmer, which also fulfilled theatre managers’ desires for single-work programmes that were easier to market than mixed bills. Other multi-act works included Dances of Love and Death (commissioned through the 1981 Tenant Caledonian award for the Edinburgh festival) and The Phantasmagoria (1987).

Cohan drew on a wide range of sources. The witty Waterless Method of Swimming Instruction (1974) was based on a swimming manual, the dancers moving in a dry swimming pool. The fluid, impressionistic Nympheas (1976) combined the inspiration of Monet’s water lilies, enlarged details of which were included on the dancers’ body tights, and Debussy’s music. Stabat Mater (1975) used an all-female cast representing facets of Mary, mother of Christ, grieving at the foot of the cross. The blues to maroons of the costumes reflected the sky’s colours at dusk watched by Cohan from the home in the south of France he shared with his friend Chiesa.

Cohan played an important part in developing design for dance. He was not only responsible for the costumes for some of his own productions and encouraged the use of sculptural and built sets rather than painted cloths, but also was instrumental in introducing American-style lighting for dance. Khamsin (1976), with its shiny floor, use of fabrics, and impressive lighting, focused as much on design as movement.

His career was far from over when Cohan stepped down as artistic director of LCDT. He had a parallel career working in Israel with the Batsheva and Bat-Dor contemporary dance companies and in 1980 he became an artistic adviser to Batsheva. With Scottish Ballet he worked with ballet-trained dancers on A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1993) and Aladdin (2000). Much of his later work came from a network of former students around the world requesting revivals of productions they loved.

Although his style of dance has fallen out of fashion, it was still taught at Middlesex University, with the Yorke Dance Collective. Cohan received many outstanding achievement awards, including the Evening Standard award 1975, Society of West End Theatre award 1978 and the De Valois award in 2013, as well as honorary degrees from many universities. In 1988 he was made an honorary CBE and, having become a British citizen in 1989, he was knighted in 2019.

His personal archive has joined that of Contemporary Dance Trust in the Theatre and Performance Collections at the V&A in London.

• Robert Paul Cohan, dancer and choreographer, born 26 March 1925; died 13 January 2021