Selfies in the Korean DMZ – and other unusual border travel experiences

Such is the political turbulence that has come to define this second decade of the 21st century that it seems we can go from the worrying - and uncomfortably plausible - prospect of global nuclear warfare to selfies on the frontline in the space of less than 18 months.

The saying that "life comes at you fast" is a relatively recent, internet-fuelled addition to common parlance. But even so, this pithy directive is about the only expression you can use to sum up the announcement that tourists will soon be able to pose for photos at a spot that, barely minutes ago, seemed sure to be a flashpoint for the death of us all.

This is the news emerging from South Korea that, soon, travellers will not only be able to visit the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) which divides the two not-so-good neighbours of the Korean Peninsula - they will be able to hop back and forth across the precise "Demarcation Line" in the middle of the Joint Security Area (JSA) that, for more than 40 years, has been so starkly guarded that few have dared to cross it.

The Ministry of Defence in Seoul has revealed that international travellers will be allowed to walk onto the north side of the site "in the near future".

It has also declared that South Korean nationals - who have been banned from visiting the JSA (except in rare cases of family reunions with elderly relatives) ever since a truce put hostilities between the two warring nations on hold in 1953 - will also be allowed to join in with the "fun".

What fresh madness is this? Let us quickly remind ourselves of all that has happened in recent history.

It was but August 2017 when Donald Trump promised to rain "fire and fury like the world has never seen" on North Korea. In this entirely moderate and restrained statement, the US president was responding to reports that said rogue state had stepped up its weapons programme to the point of creating a miniaturised warhead to fit inside its missiles. A North Korean spokesman then replied with a not-so-veiled threat which suggested that his bosses were planning a nuclear strike on the US Pacific Territory of Guam that would teach the USA a "severe lesson". And it was but September 22 2017 when North Korean leader Kim Jong-un unleashed a verbal howitzer in Trump's direction, saying: "I will surely and definitely tame the mentally deranged US dotard [a 14th century English term for a slow-thinker] with fire". Ouch.

Still, if a week is a long time in politics, then a year is virtually an Ice Age - and much has happened since. In April of this year, President Moon Jae-in of South Korea stood face to face with Kim Jong-un at the Demarcation Line, in a meeting which constituted the first official summit between the two nations in more than a decade. And in June, Trump and Kim met in Singapore for discussions which seemed to herald a new and friendlier relationship between Washington DC and Pyongyang.

Has the cracked pane of glass separating South Korea and its powerful ally from the communist state on its doorstep mended so much in a year that the location which has come to represent their animosity is now a viable location for Instagram self-indulgence? Good lord, it appears so.

It is worth stressing here that foreign tourists have long been able to peek into one of the planet's most notorious places - although they have had to do so via (very) carefully regulated official tours.

In May last year, Telegraph Travel writer Julian Ryall detailed a visit to the DMZ, sketching out a netherworld which "reveals a double line of tall, chain-link fences topped with razor-wire" - with, behind, "a network of bunkers and strong-points, all manned by South Korean troops monitoring what their counterparts in the North might be up to."

The JSA within it - which was once the unassuming village of Panmunjom; a tiny dot on the map located some 33 miles north-west of the South Korean capital Seoul - is the only point at which North and South Korean troops look directly at each other, across a distance of a few metres. It has long been a tense bottleneck - not least since 1976, when two US Army officers, called into the JSA to trim a tree which was partially obstructing the view of the area from the south, were attacked and killed with an axe by two soliders from the North. And the Demarcation Line is no false barrier - crossing it without permission is an act certain to invite gun-fire. Nonetheless, around 100,000 tourists venture to the JSA each year. Ryall's piece also quoted the document each is required to sign, saying their visit "will entail the entrance into a hostile area - and the possibility of injury or death as a result of enemy action."

It may be that such warnings are less strident in future. The move to "open up" the JSA has been born of a meeting between Moon Jae-in and Kim Jong-un in Pyongyang last month. The talks appear to have been so affable that the "disarming" of Panmunjom may occur in the next few weeks. The number of military personel may be reduced, and sentry posts may be pulled back to a less confrontational distance.

In some places, the de-escalation is already in progress. This month, both North and South have been clearing landmines in the DMZ as part of a long-overdue operation to find the remains of soldiers still missing from the Korean War (1950-1953). Friends? Not quite. Winter is always close on the peninsula, but a quiet thaw seems to be under way.

This increased "accessibility" is only likely to boost the appeal of the DMZ to visitors. But if, amid the general weirdness of the 21st century, the Demarcation Line in the JSA does become a staple of social-media feeds, then it will only be joining the ranks of unusual international boundaries which make up the grand tapestry of travel.

The following deep grooves on the map also offer opportunities for unusual experiences...

India-Pakistan

While not quite enemies in the Korean style, India and Pakistan can never be described as "best buddies".

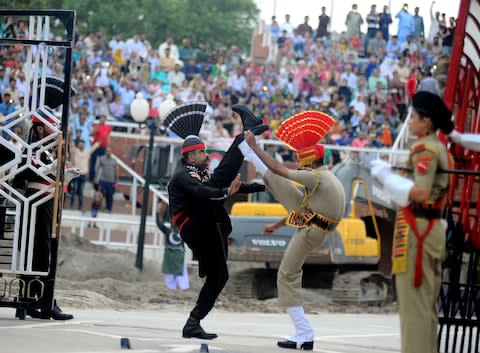

Their enmity is most oddly visible at Wagah, a village pitched at a point where the Pakistani province of Punjab rubs against the Indian state of the same name. It sits (on the Pakistani side of the border) on the Grand Trunk Road - a major trade artery between the two countries - and is thus an important customs point. But its border ceremony, held every evening, goes far beyond paperwork and passports.

It sees troops from both countries performing elaborate, quasi-balletic drills - all high kicks and athletic moves - while a vociferous crowd of spectators, of people from both nations, looks on and cheers/jeers. It has been held on a daily basis since 1959 - and while ostensibly a symbol of co-operation, it can also be marked by partisan tensions, depending on the warmth (or not) of relations between the two countries. Last year, Jack Palfrey penned a piece about it for Telegraph Travel which outlined its eccentricities. Read more here.

Cyprus-"North Cyprus"

When is a border not a border? When, as far as most of the world is concerned, it does not exist.

Such is the case with the frontier that runs east-to-west across the torso of Cyprus - between the Republic of Cyprus (on the southern side of the landmass) and the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (which, somewhat obviously, is in the north). Only Ankara recognises the latter, which came into "being" following the Turkish invasion of the island in 1974. Every other nation regards Cyprus as one sovereign state - whose upper half has been occupied territory for over four decades.

Nonetheless, the 112-mile "Green Line" - as the United Nations Buffer Zone between the "two countries" is generally known - is a very real thing for anyone trying to move around the island. For a long time, it was heavily fortified, and entirely closed. Since 2003, however, comings-and-goings have been permitted - and there are now seven official crossing points.

The most evocative is found on Ledras Street in Nicosia. The Green Line cleaves the Cypriot capital in two (to the point that the Turkish side knows the city as "Lefkosa") - and there are still watchtowers and patches of barbed wire in prominent positions. But there is a gap on this key boulevard - which holders of EU passports are able to stroll through on presentation of their ID. If you walk from south to north, you leave an area of inviting shops, restaurants and cafes, and enter an area of... inviting shops, restaurants and cafes; the narcissism of small difference writ large.

Colombia-Panama

When is a border not a border (part two)? When no-one is entirely sure where it is, and few people - beyond the brave and foolish - have attempted to cross it in half a century.

Such is the situation with the Darien Gap, the isthmus that connects South America to Central America, and Colombia to Panama. "Connects", that is, in a geographical sense, but in few other ways. Until recently, this "land bridge" has been a no-go-zone thanks to its use as a training area by anti-government guerilla groups waging the Colombian Civil War. Travellers reckless enough to seek a way through have been kidnapped and held to ransom - or shot and killed, as with Swedish backpacker Jan Braunisch in 2013.

There are other ways in which the Darien Gap is seen as impassable. The land is swampy, insect-infested and heavily rainforested. Its unsuitability for construction is one of the reasons why the 19,000 mile Pan-American Highway is 60 miles short of being an unbroken ribbon from Alaska to Ushuaia in Argentina - the 60 miles being those between Yaviza in Panama and Turbo in Colombia, where the tarmac stops. Somewhere in between is the border, although you will not find customs booths or fluttering flags, and you will be hard-pressed to know if and when you have crossed.

Despite its reputation, the Darien Gap has become a little more "visitor-friendly" of late - due mainly to the cooling of the internecine conflict in Colombia. You need to be able to cope with the terrain and the mosquitoes, but Steppes Travel (01285 601 754; steppestravel.com) sells a part-guided "Darien Gap, Caribbean Coast and Medellin" trip which dissects Colombia in 14 days. From £3,850 per person - including flights.