The rock star of retail: how Topshop changed the face of fashion

“What’s this I’m reading in the paper? It’s a load of absolute shit, that’s what it is. What’s the matter with you? Are you stupid or what? I’ve never read so much rubbish in my life.”

It was February 2010, and I was at my desk in the Guardian office. Philip Green didn’t need to introduce himself. His habit of bellowing down the phone was unmistakable, and I had just written an article about how I was falling out of love with Topshop after a decade being in thrall to its shop floor. Green never did take kindly to criticism of the golden child of his Arcadia empire.

Of the thousands of businesses that have been brought to their knees by the pandemic, Topshop is the most high-profile scalp; Arcadia Group collapsed into administration on Monday. In its prime, it was the most glamorous store the British high street has ever had. From late 1990 until a few years ago, it was the rock star of retail. Its dresses regularly featured on the pages of Vogue. Every Saturday, the 90,000 sq feet of its flagship store on Oxford Circus were packed with shoppers high on catwalk-adjacent clothes at accessible prices. When Beyoncé flew into London, the store opened an hour early so that she and her team could shop privately on their way to rehearsals. At London Fashion Week, where the brand staged a bi-annual show from 2005 until 2018, the Topshop front row regularly outshone designer labels with the glossiest celebrities, the sharpest new trends, the most copious champagne. At those catwalk shows, Green would position himself in the place of honour, with Anna Wintour on one side and Kate Moss on the other. He was the uncontested king of the high street.

The story of Topshop’s glory years – and of its fall – is closely tied to Green, but the story of its rise belongs to someone else. Topshop’s ascendancy was a phenomenon under the stewardship of Jane Shepherdson, several years before Green arrived. As brand director, Shepherdson created at Topshop the kind of brand that had never before existed. Until then, high street fashion had tended to fall into two generational camps. There were sensible skirts-and-blouses for grownups, and then there was “youth” fashion – basic denim, brightly coloured T-shirts, generically skimpy party dresses, cheap rip-offs of catwalk silhouettes. Topshop changed this, thanks to Shepherdson’s unerring taste and her eye for the best fashion school graduate talent with which to fill the design studio. Topshop offered high-fashion sophistication at a high street price. In 2006, Paolo Roversi shot a Topshop advertising campaign between shooting covers for Italian Vogue.

Fashion is never just about clothes, and Topshop on a Saturday in the noughties was a playground. The democratisation of style that it represented felt like a progressive and cheering development, and the loud music and video screens lent the stores a festival mood. There were on-floor stylists and walk-up nail bars. Green, who bought Arcadia in 2002, had little time for the nuance of design but he immediately grasped the value of the shop floor experience that Shepherdson had created at Topshop (“Fashion Disney,” she once called it). There are not many points on which Green and I agree, but he was right about one thing: he knew that the business of fashion is about emotion. A man ruled by ego, he instinctively knew the power that clothes have to make you feel good about yourself. For a certain type of consumer, a Savile Row suit signals status to everyone who matters; Green understood that the same principle could be rolled out for a £50 leather biker jacket that could be sold by the lorryload.

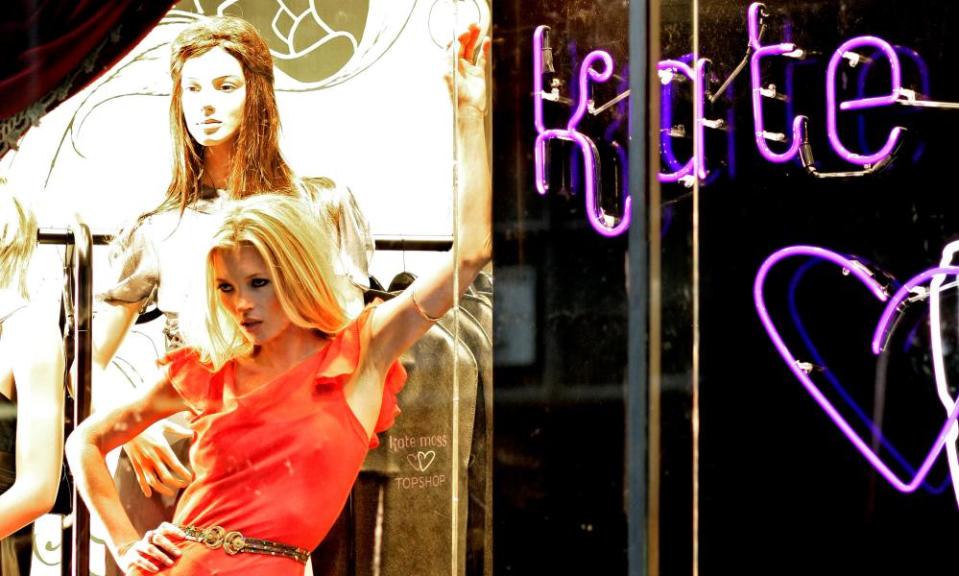

The rise of Topshop is a tale of how fashion reached its zenith. In the first decade of the 21st century, culture shifted away from words and towards pictures. The world’s operating systems became ever more visual on a granular level, as mobile phones segued from being about the spoken or typed word to being about images. As a result, fashion became ever more visible. The luxury industry grew, so fashion brands became wealthier and more powerful. Fashion weeks evolved from being industry-facing showrooms for clothing into major media events. At the Oscars, the red carpet became as high-profile as the awards themselves. Fashion, the arena where visual messaging meets identity politics, found itself in the spotlight, and Topshop rode the crest of this wave. In May 2007, just a few months after the arrival of the first touchscreen iPhone, the first Kate Moss for Topshop collection went on sale. Launch night brought Oxford Circus to a standstill. Moss, dressed in a long ketchup-red dress from the collection, struck mannequin poses in the shop window to entertain the waiting crowds, before being escorted by a beaming Green to a cordoned-off VIP area, where friends including Meg Matthews and Sadie Frost joined her. This was a world of supermodels, champagne and rock’n’roll, and the name above the door was Topshop.

Retail theatre has always existed among the highest echelons of fashion, and among its lowest, but until the 21st century it was missing from the high street. At its best, a visit to an expensive boutique is performance art, from the elaborate courtesy of a doorman that marks your arrival to the lavish rustle of tissue and ribbon that accompanies your exit. Shopping at a street market, in a different way, is an equally immersive experience: a world of larger-than-life personalities, drama and banter. A department store womenswear floor, however, was once a dry and dreary world where a half-hour wait for an assistant to check the stock room for a size passed in a torpor of lift music and the desultory rustle of plastic hangers. Then came noughties Topshop, which along with H&M brought event fashion to the high street with designer collaborations that turbo-charged the shopping experience into a hot-ticket moment. Topshop’s collaborations were an intoxicating mix of fun and genuine bargains – I still have, and still wear, a sundress from that first Kate Moss collection, and a velvet and lace party dress from a Christopher Kane for Topshop collaboration bought the same year. It is no secret that Shepherdson and Green never saw eye to eye – when, after several years overseeing from a distance Green moved to take closer creative control at Topshop, Shepherdson made a swift exit – but the combination of Shepherdson’s passion for fashion and vision for the possibilities of customer experience with Green’s appetite for grandstanding made for a great show.

For Green, Topshop was always personal. Once, when my Guardian fashion desk colleagues and I were being talked through a new collection in the brand’s showroom, he marched in, unhappy about something we had written, and demanded an apology. When none was forthcoming, the conversation deteriorated until he insulted, in my recollection, the size or shape of someone’s nose. By now we all know that this was nothing compared with the bullying and abuse reported by some employees. Green denies any “unlawful … racist or sexual behaviour”. But even before allegations about serious misconduct came to light, his behaviour was coming to seem increasingly out of step with the expectations and values of his target market. Generation Z have changed culture for all of us. They have no time for a billionaire who expects to stand on the deck of his yacht and shout into a mobile phone, rather than listen to what they have to say.

First, Topshop found itself threatened by cheaper brands such as Primark. This was perhaps less a business failing on the part of Topshop than a symptom of the structural catastrophe of a cycle of ever-cheaper fast fashion. (If Topshop had slashed its production costs to compete in a marketplace of £10 jeans, it would have been nothing to cheer.) What happened after that, though, is a bit more complicated. With the rise of Boohoo and Missguided, Topshop was overtaken by brands that, like its target market, saw shopping as oriented around phone screens and the young influencers who hold the power in that magical world, not shop floors and their middle-aged bosses. That it would be overtaken by a new generation of brands was perhaps the price that Topshop paid for becoming a high street rock star. No teenager wants to listen to her mum’s music once she can assert her independence, after all. Why would she want to wear her mum’s fashion brands?

Yet of all the Arcadia brands, Topshop has the best chance of a second act. In a crowded marketplace, a globally recognised brand that was at one time synonymous with the giddy thrill of shopping remains a valuable commodity. But to reclaim the potency it once had, it will need to look very different.

For a brand to seize the imagination today in the way that Topshop once did, it has to embrace a serious commitment to sustainability. It is no coincidence that Shepherdson, a woman who has been on the front foot of the zeitgeist since the 1990s, has now shifted out of retail into rental, as the chair of My Wardrobe HQ, the UK’s largest fashion rental platform.

For the past four years, Green has ruled the headlines as the villain of the Topshop piece – but the fast fashion industry had a deeper, more poisonous dark side all along, with the long tail of environmental damage wreaked by clothes that have a six-week shelf-life. Topshop was once about the future. To get back there it will need more than just a few new clothes.