'Pretty Woman' at 30: Screenwriter JF Lawton reveals truth behind the myths surrounding the iconic romcom

This month sees the 30th anniversary of what many consider the greatest romcom of all-time – Pretty Woman. Starring Julia Roberts and Richard Gere as a prostitute and the billionaire who picks her up and who falls in love with her, it launched Roberts’ career, spawned a mega-hit soundtrack and became a benchmark for romantic comedy. In the decades since its release, it has also precipitated doctoral theses about whether the storyline was problematic (hooker with a heart of gold, anti-feminist).

Whatever your take, it remains iconic, a movie with a host of myths about its inception, original script and ending. We asked writer JF Lawton – currently working on the film’s stage musical adaptation which has just premiered in London – for the real story.

Lawton was a struggling screenwriter when he wrote a dramatic script in response to provincial 1980s industrial downsizing and the women he met at his local Hollywood donut shop who had travelled to the west coast when their blue collar communities were devastated by corporate sharks.

He called it Three Thousand – note the words spelled out and not the number. This was its title, but through the years people mistakenly started calling it 3000, as development executives would scrawl the figure on the spine of the pages.

Myth: The studio didn’t want Julia Roberts or Richard Gere - False

Casting rumours on this one are difficult to clarify, mainly because it’s unclear whether some of the actors touted for the lead roles were being considered when it was a dark indie or a glossy studio romcom. Molly Ringwald, Brooke Shields, Daryl Hannah, Emily Lloyd and Winona Ryder were in the mix, while it’s said that Valeria Golino (Rain Man) was extremely close to getting the role. For Edward, Christopher Reeve, Dennis Quaid and Christopher Lambert (Highlander) were discussed.

Read more: Richard Gere thinks Pretty Woman relationship wouldn’t have lasted

“My manager at the time, Gary Goldstein, who went on to be an executive producer of the film, instantly said he knew exactly who should play the role – Julia Roberts,” remembers Lawton. “At that time she was only known for Mystic Pizza, but Gary was certain she was perfect for it. When Vestron optioned the script, Gary pushed for her and she was briefly attached to it. When Touchstone picked up the rights, they were more hesitant to go with Julia and for a while other actresses were considered, but Gary Goldstein kept fighting for Julia and of course, he was right.”

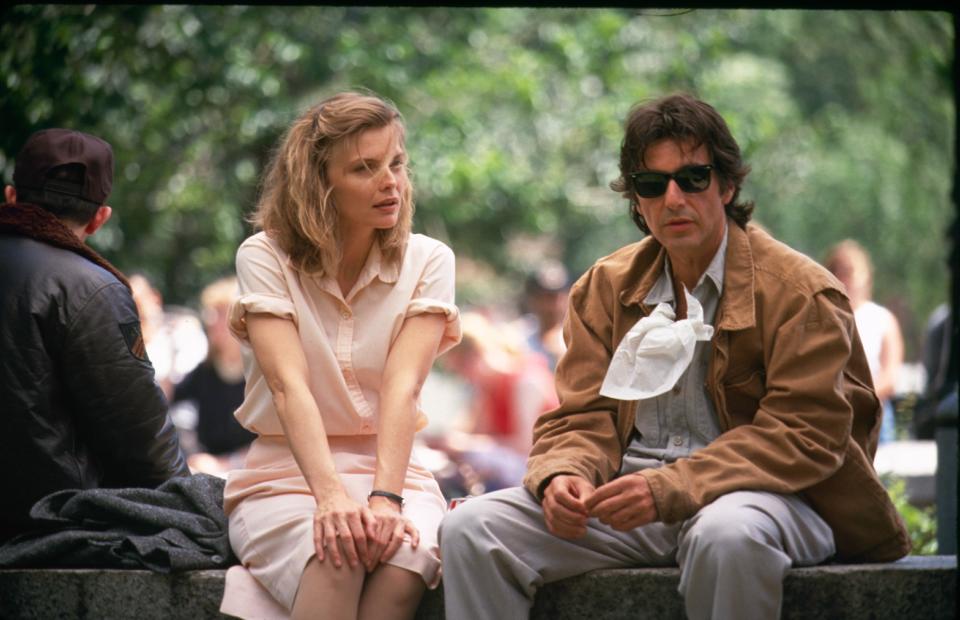

“There were serious discussions about casting Al Pacino and Michelle Pfeiffer,’ he continues. “As you might imagine, that version probably would have been closer to the original. But after Gary Goldstein got them to test Julia Roberts, they pretty quickly signed her. Edward was much harder to get cast because it was viewed as Vivian’s story and in the original script he was pretty unlikable. I know they were turned down by many stars at the time, like Burt Reynolds and Tom Berenger, before they were able to convince Richard Gere to do it.”

Myth: It was close to being filmed in its original downbeat state - True

“The Sundance Institute selected the script for its prestigious workshop and it was then quickly optioned by a small company called Vestron (who made Dirty Dancing) with the plan of making it as a low-budget independent film,” says Lawton. “But Vestron ran into financial troubles and [producer] Arnon Milchan got the rights to the script in turnaround. He decided to try to get it made at a major studio.

“There was a bidding war between Universal and Touchstone Pictures. Arnon closed the Touchstone deal and Garry Marshall was assigned to direct it. They greenlit the movie based on the original script and they were already building sets by the time I took my first meeting at the studio.”

Touchstone and Marshall had recently had success with bittersweet comedy Beaches and Marshall took on Pretty Woman thinking he could heighten the fish out of water story aspect, while still mixing laughs and tears as he did in that movie. Three Thousand was gritty, but it had laughs and some of the Pygmalion-style elements we see in the end product, like the opera visit and high-end shopping trips.

Still, Lawton says, “at first there was no intention of making it a full out romantic comedy. In fact, the Touchstone executives initially said that the characters couldn’t end up together, because that would be a cop out. There was talk about Vivian going to work at the hotel, or ending up with David (the polo playing grandson of Mr. Morse, the shipbuilder).

Myth: Vivian and/or Kit dies at the end of the original story - False

The Three Thousand screenplay is a very different animal to Pretty Woman. In it, Vivian is quite open about her desire to smoke crack during the week she’s with Edward, she’s pimpier towards Kit (Laura San Giacomo) and the pair buy drug paraphernalia at the beginning.

Meanwhile he is significantly crueller, bordering on awful. Aside from his irredeemable callousness in business (there’s no building things), he happily banters with his lawyer (called William Reaves here rather than Phil Stuckey) that William should sleep with Vivian when he’s finished, all while she’s listening. Even worse, when William propositions and then hits Vivian, Edward punches him and bundles him out of the room, but doesn’t really criticise his behaviour and ultimately seems to laugh it off.

But, says, Lawton, “No one dies at the end. The basic story is very similar, Vivian and Edward make a deal for six days for three thousand dollars, but at the end of those six days Edward doesn’t fall in love with her. Vivian however, kind of imagines she loves him or at least doesn’t want to go back to her old life.

“Edward drives her back to Hollywood Boulevard and they get into an argument, with Edward not understanding why Vivian is so upset. When she won’t get out of the car, Edward tries to pull her out and she starts hitting him. He throws her off and as she is sobbing, he tries to give her the money in an envelope. She won’t take it, and when he puts it on the curb for her, she grabs it and throws it in his face. But as he drives off, she slowly picks the money up from the street.”

Read more: Original ending of Pretty Woman revealed

There was though, something of an optimistic coda.

“Vivian and Kit are on a bus heading to Disneyland and have an innocent conversation about getting a balloon with mouse ears,” explains Lawton. “My hope was that [the audience] would see a transformed Vivian who has to confront her life choices after this experience and hopefully will take a more positive path forward.”

Myth: They didn’t know the ending even after they started filming - True

“There was still a ton of uncertainty about the ending,” admits Lawton. “But once the footage started coming in, the chemistry between Julia and Richard was so strong, it was clear they had to end up together in the end.

“Some people criticise the story for being unrealistic (which is weird since most movies aren’t realistic), but if you watch the first half of that movie, despite coming from such different worlds, the growing love between Julia and Richard is so believable that I don’t think any other ending would have been true to those characters as they were portrayed.”

Myth: It’s a problematic, anti-feminist movie about a billionaire rescuing a ‘hooker with a heart of gold’ - Inconclusive

Lawton is loathe to mansplain, pointing instead to writings by authors like Mari Ruti, who discussed the film in her 2015 book, Feminist Film Theory and Pretty Woman. In that, Ruti suggests that it received particular criticism due to its nature as a popular romcom, writing the movie “walks a tightrope between retrograde, potentially anti-feminist themes and progressive, potentially feminist ones…Feminist analysis of the film should perhaps focus less on its alleged misogyny than on the version of female empowerment it endorses.”

But Lawton does have his own opinion. “While it certainly isn’t a feminist film, it does have a higher level than expected of ‘embedded feminism’ than a typical romantic comedy,” he says, using a phrase coined by critic Susan Douglas to suggest persistent traces of feminism in a cultural product.

Read more: Pretty Woman director dies aged 98

“Some say it’s about a billionaire who rescues a prostitute,” he continues. “No, it’s about a woman who walks out on a billionaire and he has to chase after her. Vivian stands up for herself and it is Edward who has to change.

“In retrospect, neither [director Garry Marshall or I] realised that we had hit the third rail so to speak, of society’s incredible hypocrisy on the issue of prostitution. Pretty Woman is fundamentally a story about a woman who decides not to be a prostitute. She goes from being willing to sell herself for $100 an hour to not being willing to be bought at any price. What could be wrong with telling that story?”