'People were like animals!' How supermarket staff watched the coronavirus crisis unfold

It was Thursday night, 8pm. Clap for our carers: the sound of applause rising in the air. Leila was doing her rounds of the Waitrose in west London where she works as a store supervisor, rounding up the stragglers. An expensively dressed young woman was browsing the aisles. Leila asked her to make her way to the tills, as the store was now closed.

The woman erupted in rage. “She said: ‘There’s a f****** pandemic, can’t you have a little patience?’” Leila remembers. “I thought: ‘I am working through this pandemic. You’re just shopping in it.’” Shaking with anger, Leila fetched a security guard, who escorted the woman to the tills. Leaving work that evening, the irony of being verbally abused during the weekly celebration of key workers was not lost on her.

“The public has this sanitised image of what a key worker is,” Leila says. “They think a key worker is a consultant in a suit, or a nurse in scrubs. They don’t consider us key workers – they just think we’re unskilled. There have been so many instances of people getting frustrated, angry, taking things out on us.” She sounds fatigued. “You just feel kind of empty about it, I guess.”

But supermarket workers are key workers, exempt from the lockdown restrictions that have kept so many of us at home over recent months. And as essential workers, they were there for the initial panic-buying through to our bread-baking mania and everything in between. No one is better placed to comment on how we, as a nation, responded to the coronavirus crisis than our supermarket workers.

“Oh man,” remembers Alex Hogan, of those March stockpiling days. “The panic-buying was just crazy.” Hogan, who is 22 and lives in North Ayrshire, works as a checkout operator at the biggest Tesco in Scotland, in the south of Glasgow. “People would be pushing past each other in the aisles, and they would become quite protective of their shopping, as well,” Hogan says.

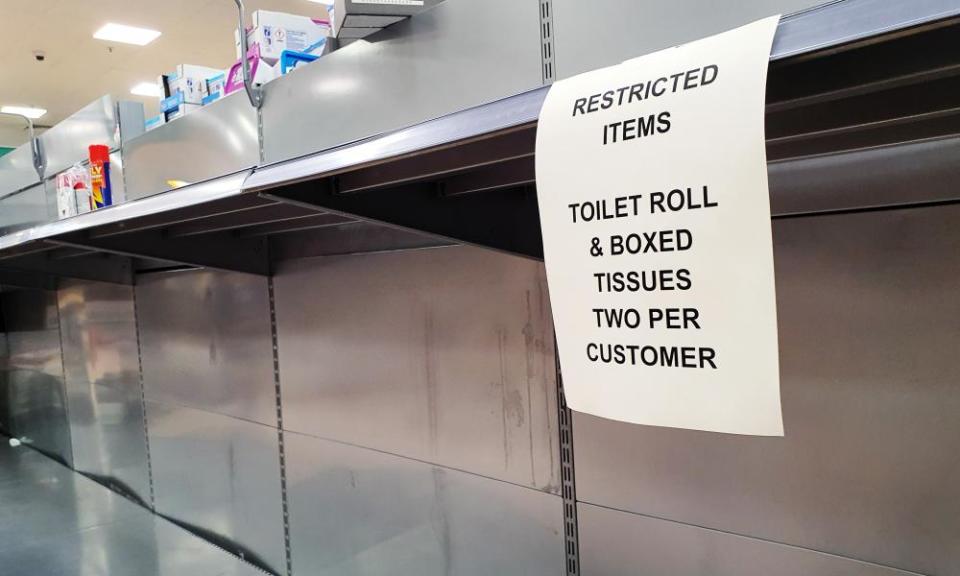

For about a fortnight, Britain became a nation obsessed with loo roll. And antibacterial hand gel. And soap. And pasta. And tinned goods. But mostly loo roll. “People were like animals,” Leila says. “They were just going for the toilet paper the minute they saw it.” In her branch of Waitrose, only managers were allowed to replenish the pasta and toilet paper during those initial weeks. “One of my managers told me that he didn’t even try to put the toilet paper on the shelves – he just left it on the crate,” Leila says. “People were taking it the minute it was out. There was such a swarm of people.”

During this period, some shoppers behaved disgracefully – particularly after the major supermarket chains brought in restrictions on how many items shoppers could purchase in an effort to curb stockpiling. “Around the time they brought in the restrictions I had some of the least enjoyable shifts I’ve ever done,” says Warren, a general assistant at one of the big four supermarkets (he prefers not to say which) in Gloucestershire. Like Leila and Hogan, he got in touch after a Guardian callout for supermarket workers. Warren had to tell one customer that he could only buy three tins of tomato soup, not 20. This did not go down well, and the customer demanded that Warren brought over his supervisor. When Warren’s supervisor confirmed that, yes, he could only purchase three tins, he demanded to speak to the store manager, who said the same thing.

Had he behaved more respectfully, Warren would have told the customer that he could have circumvented the restrictions by buying tomato soup from different brands. But he was so rude, Warren didn’t want to. “That’s a weird feeling for me,” says Warren, “because even though this isn’t a great job – it’s not well paid and you can’t afford much, or any, quality of life, really, on the minimum wage – it’s still a job. I take pride in what I do. I want to help people. But when customers are shouting and causing a fuss, you don’t want to help them.”

It was not just the customers piling on the pressure during those early days. “The managers were blasting out the orders,” says Gavin, a warehouse worker and shop-floor replenisher at a big supermarket near Cardiff. “Especially because a lot of people were off sick, they hadn’t recruited enough extra staff, so they were having to push a depleted workforce. They’d be pressuring staff on headphones to put more items on the shelves.” For some of Gavin’s colleagues, it was too much. “They’d be coming up to me, stressed out of their heads, because after an eight-hour shift the tensions and frustrations with customers and managers was so high.”

Gavin’s experience is not unique. “Even before coronavirus, there had been a rising problem of violence and abuse to supermarket staff,” says Doug Russell of the USDAW union, which represents approximately 260,000 shop workers, including staff from Tesco, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s, Co-op and Asda. “Unfortunately, the Covid-19 crisis added to that, because it required shop workers to limit the numbers of people going into stores and enforce social distancing and restriction on sales of products, which can be flashpoints for abuse.”

There is evidence that supermarket staff feel stress more acutely than other frontline workers. Dr Rachel Sumner of the University of Gloucestershire has been conducting research into the health and wellbeing of frontline workers during the pandemic. Of the 1,300 people who responded to her survey, about 86 were supermarket staff. “These workers had higher levels of burnout and stress than both other types of frontline workers, and population norms,” says Sumner. Additionally, supermarket staff were less likely to think the government’s response had been timely and effective than those from the emergency services.

Sumner speculates that this burnout and stress is due to the fact that most supermarket staff didn’t plan to be on the frontline in any conventional sense. Unlike medicine, nursing or police work, supermarket jobs are predominantly minimum-wage, without the higher earnings, benefits or sense of vocation enjoyed by many emergency personnel. “The thing is, these people never thought they would be on the frontline of a pandemic,” says Sumner. “Your police officer or nurse, to a certain extent, they expect to be frontline. But a checkout worker or Amazon delivery guy, they never expected they would be getting spat on or shouted at.”

But it has not all been abuse. After the stockpiling abated, and the restrictions were lifted, the British public settled into a kind of equilibrium. “When everyone was panic-buying, people were a lot more abusive,” says Hogan. “But when clap for our carers came in, people stopped doing that as much.” She’s noticed customers are more talkative than usual. “I’ve had customers tell me they live on their own,” Hogan says, “and they seem quite lonely. And then there are parents who tell me they’re trying to home school their kids, and they’re stressed out. I think people miss having that human interaction they’d have from seeing their friends and going to work.”

But, with normal order being restored, physical distancing rules are starting to be ignored by some members of the public, as is the government recommendation to shop as infrequently as possible. “The majority of people are still social distancing,” says Russell, “but many aren’t. And the more we get confused messages about lockdown being relaxed, the more problematic it gets for workers in shops, because you get more people wanting to nip in for something quickly.”

All of the supermarket workers I speak to agree. “How do you stop customers coming right up to you and asking you for the frozen peas?” muses Gavin. “When they’re in the store, they want to get out of there as quickly as possible. They take no notice of the signage, they ignore the two-metre rule … There’s a melee to get in and out as fast as they can.” Now, when customers approach him, he holds out the palm of his hand, like a police officer stopping traffic. “My first instinct was to ask them not to come up so close,” Gavin says, “but by the time you ask politely, they’ve already ignored you. All they see is a uniform, not a person, and all they care about is finding an item.”

Inevitably, working in an enclosed space such as a supermarket will increase a worker’s risk of contracting Covid-19. Recent data from the Office for National Statistics shows that male sales and retail workers have Covid-19 death rates that are twice the national average. Distribution of personal protective equipment (PPE) varies among the major supermarket chains: Warren has been given rubber gloves, but they make it difficult to operate the self-scan tills, which ends up annoying customers.

One worker at an Asda in south Wales told me staff had been given no form of PPE whatsoever. “After about four weeks some bottles of hand sanitiser appeared in the rest rooms, but we’ve been given no individual hand sanitiser,” he says. “I get paid £9 an hour to put my life on the line,” says the worker, whose age (he is in his 60s) puts him in the higher-risk group for coronavirus. “That’s not being over the top about it. We are putting our lives on the line, for £9 an hour.”

In response, Asda commented: “We have worked with our colleagues to provide them with extensive support throughout this period and we are proud of the work they are doing every day to serve customers. Although colleagues haven’t raised concerns with us … we’re doing everything possible to support them as they carry out their vital roles, such as providing gloves, masks and Perspex screens.”

Of all the supermarkets, Waitrose appears to have been the best when it comes to offering PPE to staff. “They’ve given us masks and visors, gloves, loads of sanitiser, and we have protective screens at all the checkouts,” Leila concedes. “I can’t fault them.”

Hogan’s mother is in a high-risk group for coronavirus as a result of a kidney transplant. When she gets home from work, Hogan takes off all her clothes at the front door, and showers immediately. But she worries it’s not enough. “My mum hasn’t been going out,” Hogan says, “so if she was to get symptoms, I know it would come from me. I’m a bit anxious. I have to make sure that doesn’t happen, which is why I’m super-careful.”

As for the wider public, what better indication of how they are coping than their shopping baskets? In the Waitrose where Leila works, the predominantly middle-class customers have sought comfort in familiar pleasures. “We sold out of Charlie Bigham’s ready meals really quickly,” Leila says. “Another hilarious thing we sold out of is manuka honey – I think because coronavirus has respiratory symptoms. Everyone’s buying a lot of alcohol and fancy meat.” One customer kicked up a fuss because they had purchased £3,000 of wine but couldn’t get a delivery slot.

But there are more subtle indicators that all is not well. Shoplifting is up, for a start. “I think because security is so busy manning the queue, there are a lot more shoplifters,” says Leila. “Two weeks ago, someone nearly got away with £500 worth of alcohol.” In addition to the professional shoplifters, who target high-value items such as alcohol and meat, and steal to order, Gavin has noticed more “pilfering”: shoplifting cheaper minor essentials. “I think it’s people who are now suffering economically who are taking things because they can’t afford to pay for them,” he says. “People haven’t been paid for a while, and they’ve come to the supermarket and for the first time in their life perhaps they’ve been hungry and stolen something.”

The pilfering, the rudeness, the stockpiling and more: truly, the supermarket worker saw it all. And having a front-row seat during this period of national crisis has been a simultaneously heartening and dispiriting experience. “I’ve had people say: ‘You’re doing really important work,’” says Warren. “But as with life in general, you tend to remember the bad stuff – the customer who called you a twat, rather than the one who patted you on the back.”

Hogan hopes that the lockdown will usher in an era of greater respect for low-paid workers. “Before, when people would ask what I do, they would be quite judgmental,” she says. “They’d say: ‘Why don’t you do something else?’” Not any more. “People will come up to me and say: ‘Thank you for being on the checkout.’ I’ve never had that before.” She sounds surprised. “I just hope it lasts.”

Some names have been changed.