This Mutton Soup You Didn’t Even Know Existed Was Invented In Singapore

Images from Golden Mile Food Centre/Deen Tulang Specialist by Zachary Tang.

Ask a random person on the street about dishes invented in Singapore, and you’ll get a mix of answers, from Chili Crab and Fish Head Curry to Yu Sheng. More knowledgeable foodies might point you to Indian Rojak or Kueh Tutu. But most people won’t know that Sup Tulang or Sup Tulang Merah was invented in Singapore.

This is assuming they even know it exists.

Not that I blame them. Top Singaporean food blogs show a dearth of mentions of the dish. If it weren’t for Anthony Bourdain’s feature on No Reservations, visitors to Singapore who have to mostly rely on clickbait TOP TEN MUST TRY EPIC FOOD articles and AMAZEBALLS CHICKEN AND RICE DISH videos wouldn’t even have heard of the uninviting dish.

Hence, even if you’re Singaporean, you might not have eaten it.

The few articles you might find on Sup Tulang all point out that the Anthony Bourdain also patronised this stall—perhaps revealing the sad fact that having someone famous eat the dish is apparently more appealing than the dish itself.

On the bright side, Bourdain’s influence also brought a bit of a challenge particularly to foreign visitors; if you can get down and dirty with your hands and leave the table feeling a blend of shame, satisfaction, and accomplishment, you know you’ve just eaten a local delicacy.

After all, eating Sup Tulang is a mess.

Be prepared to use your bare hands. Cutlery is provided, but you’d find that this is a formality rather than for any real utility, as they are too clumsy to manoeuvre around the bones. As you nibble away at the meat, bits of the thick, sweet, and sticky cherry-red sauce will inevitably splatter onto your clothes. You might pick up a chunky piece of bread to soak up the generous serving of sauce, licking and slurping at your fingers as you eat.

That’s not even the best part—Sup Tulang Merah literally translates to “Soup Marrow Red”, and the jewel in the crown is eating or sucking out the marrow.

First you’ll try to knock bits of the marrow out, fiddle with the bones a little, before realising—Oh, that’s what the narrow end of the spoon is for. This is also usually when the stall owner, watching yet another customer try the dish for the first time, brings you a straw with a knowing grin.

Then comes the hit of milky butteriness and the intense flavour of mutton, soaked with tomato, chilli, and mutton sauce.

Without trying it, most would dismiss the dish as unappealing. At the same time, take care not to eat more of it. Something that tastes this good can’t be good for your health. And remember to not wear a white shirt.

Verifying Its Singaporean Roots

Sup Tulang begins with Sup Kambing (Mutton Soup), which in itself is already considered a unique dish in the Southeast Asian region that was said to be brought here by Arabs and Indian Muslims migrating into the Malay Archipelago.

You might think that means you can trace the dish back to Indonesia or India, but it is generally agreed by hawkers that you can’t really find it elsewhere. If we were to look at similar dishes, India has a bone broth called Kharode Ka Soup, or Khurode, Paya, Paye, or even something else depending on where you find it.

There is also something like the Nihari, yet another soup stew that looks vaguely similar to Sup Tulang, and uses bone marrow as an ingredient.

In Indonesia, there is Sop Sumsum.

But make no mistake in thinking any of those might taste similar to Sup Tulang. While those are soup or broths, Sup Tulang is more like a sauce that’s cooked using soup.

With a good broth, infusing the Sup Tulang with the sweet chilli sauce allows for the transformation from Sup Kambing to Sup Tulang, which takes place relatively quickly in the span of 15 minutes. Key point: by now, the marrow has already been cooked together with the broth for several hours.

Then mix the Sup Kambing with seasoning, flour, food colouring, tomatoes, and the most important ingredient that differentiates the dish from stall to stall: the sambal chilli mixture that contains a Masala (spice mixture)—a guarded secret at every individual stall, even between family members at a family-run stall like Deen Tulang Specialist. Deen, who shows us how they cook the dish, doesn’t even know what’s in their Masala even though his Uncle owns the stall.

But if not India or Indonesia, then where?

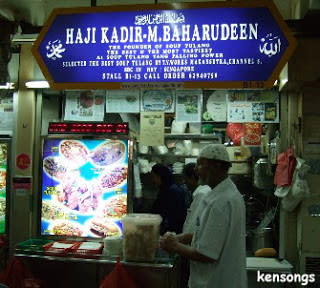

Searching for the dish’s origins led me to Mohamed Iqbal in early November. The son of Abdul Kadir, he now runs the Haji Kadir chain as a business, rather than manning the stall himself.

From Trash To Treasure

Abdul Kadir, who came from the Indian village Thopputhurai, started Haji Kadir as a pushcart in the 1950s, selling dishes like Mee Goreng, Mee Kuah, Mutton Chop, and Bistik. Mutton Chop and Bistik were particularly popular in the period when “Western” dishes were getting increasingly common.

In the 1950s, his father noticed that bones were usually thrown away by suppliers.

“When the suppliers sell to the shops, they only take the mutton (the meat) without the bones. So a lot of bones is leftover, which they cannot sell.”

The base of the soup for Mee Kuah can be said to be similar to Sup Kambing (mutton/lamb soup), which typically uses ribs, mutton meat, and legs.

“So while he’s selling Mee Kuah, he finds that it is a waste to throw away the bones, cause there’s bone marrow inside and little bits of meat around it.”

He got the bones (with marrow) for free, and would use it for the soup base of Mee Kuah. Reasoning that the marrow was edible, he also served one bone marrow to customers who ordered his Mee Kuah.

You may have heard that taxi drivers know where the best food can be found. How the marrows then became a proper dish before exploding into popularity (relatively speaking) proves this myth to be true.

“One day, one taxi driver requested of my father. ‘Kadir, can you make for me this Tulang (referring to the marrows)? I like this Tulang very much ah. I pay extra lah, you just give me the Tulang with the bones lah, I don’t want the mee,” Iqbal tells me.

Satisfied with the meal, the taxi driver asked Abdul Kadir to cook more of the marrow the next day, when he’d bring his friends over to try the dish. Customers who saw the taxi drivers eating this new creation that they had never seen before got curious, and asked Abdul Kadir for the dish as well.

Demand for the dish rose to a point where suppliers who initially gave the marrow for free started charging 5 to 10 cents per kilogram. Patrons even started asking other Indian Muslim stalls along Jalan Sultan for Sup Tulang, and stalls specialising in Mutton Chops and Bistik saw demand for these dishes dropping. Consequently, these stalls asked Abdul Kadir to stop selling Sup Tulang in hopes that sales would go back up.

This obviously didn’t make sense for any kind of business, and there was no reason for Abdul Kadir to oblige. Eventually, other stalls started making their own recipes of Sup Tulang, each with their own Masala (spice mixture) for a different gravy taste.

For all its different interpretations, Sup Tulang would retain its signature red colour from a mix of tomatoes and sambal. Sometimes, food colouring was used as a tool for consistency since customers would complain that the Sup Tulang was “pucat” (Malay for “pale”) and that didn’t taste the same.

All of this, which Iqbal told me, is also the most commonly accepted history of the dish; it is even documented on the Singapore Government-run Singapore Infopedia, and echoed by the few writers or bloggers who have talked about the dish.

That was, until I visited Golden Mile Food Centre.

It’s not uncommon for dishes to have multiple claims from inventors; the hamburger alone has at least six claims; Singapore’s Chili Crab has two different origin stories.

The Drama-Fraught History of Sup Tulang

Baharudeen.

This is the name that three Indian Muslim stalls would parrot and credit for the invention of Sup Tulang.

Abu Bakar, stall owner of Faheem Plaza, mentioned the name Baharudeen the moment I inquired about the history of Sup Tulang.

My first reaction was to immediately counter with Haji Kadir. Having missed the Baharudeen name in my research, I wondered: did someone give an inaccurate story? Why does it seem like Haji Kadir is the de facto inventor?

Abu Bakar’s account is slightly more detailed. As he recalls—adamant in his position that Baharudeen is the rightful inventor—it was in the year 1965 when he was about 8 years old that he first saw Baharudeen prepare the dish.

Hawkers like Baharudeen would hang slabs of mutton on display, slicing meat off as needed for dishes like Mee Kuah and Mee Goreng.

He then sidetracked a little, talking about how Mee Goreng in the past used to be so much more flavourful with more ingredients like tauhu and “some rojak thing”; coal was used for the fire when stir-frying, and Opeh leaf (from the betel nut tree) was used to pack the Mee Goreng.

But back to Sup Tulang.

Tulang was part of the remains of the sliced mutton, and one day, Baharudeen chopped the Tulang into a few pieces and used it for Sup Kambing (which forms the soup base for Mee Kuah). In the wee hours of about 2 to 3 AM after work, Baharudeen cooked Tulang together with chilis and tomatoes for his own consumption. As you guessed it, this formed the early version of Sup Tulang.

A customer got curious about what he was eating, which Baharudeen then gave him to try. Word of mouth then spread about Sup Tulang, and it became a regular menu item.

Abu Bakar pointed out how Tulang used to be thrown away at Beach Road market in numerous packets. It was after Baharudeen started cooking and selling that other stalls started doing the same.

“So why did Abdul Kadir say he was the one who started it?” I interrupted Abu Bakar as he points me to the direction of Baharudeen’s son, Zakariah, who now—in a surprise twist—operates a drink stall and not an Indian Muslim food stall.

Abu Bakar seemed to display a mixture of confusion and irritation at my question.

“I don’t know, I don’t know. I also say, you must believe also. I also founder, he also founder. You also selling mee goreng,” he alludes to the fact that anybody can claim to be an inventor of the dish.

Recalling the past, he said, “But I’m there that time. I know, that time I also ask him to take one. One Tulang.”

Then as if imitating another person replying to him, he mumbled, “Can take can take.”

“‘What is this?’ I asked him. That time, I’m 8 years old lah.”

He also explained that whether I wanted to believe him was up to me. After all, the supposed inventors, whether that be Bahurudeen or Abdul Kadir, are no longer in this world.

I was then brought to Zakariah, who is now manning the drinks stall M.B Deen Rasa, named after his father. You’ll find the Deen name very common among Indian Muslim stalls, as it is a common ending syllable for Indian Muslim names.

Zakariah repeats the same story about his father Baharudeen inventing the dish, adding one additional detail. Hungry customers coming from night clubs would approach the stalls in the wee hours. Without much ingredients left at the end of the day for regular menu items, it was common for customers to request for hawkers to just cook up something random from leftovers. This was eventually how Sup Tulang became a dish.

Baharudeen’s stall used to be at the front of the market at Jalan Sultan, the first stall you’ll see. Zakariah, then 5-years-old, was neighbours with Abu Bakar since Abu Bakar’s family manned the 4th stall selling Teh Tarik. In an arrangement that somewhat mirrors the current stall placements at Golden Mile, Haji Kadir was at the opposite end of the block.

Despite Abdul Kadir and Baharudeen both coming from the village Thopputhorai, they didn’t appear to be close. Zakariah’s decision to operate a drink stall now instead of working on the original recipe seems to stem on the difficulties in finding manpower. As for disputing Abdul Kadir’s claims, he wasn’t too interested in doing so.

It’s a stance that I’m naturally suspicious of.

You can find records of the stall name “Haji Kadir & M Baharudeen Sup Tulang” online, which was also the stall name when Anthony Bourdain visited. Whereas if you visit Haji Kadir now, it is lacking the “M Baharudeen”.

When I contacted Iqbal again asking about Baharudeen, he was clearly agitated in his replies, and refuted the Baharudeen claim to the dish. He had rented the Baharudeen stall from 1998 to 2014 to reduce competition.

The years of rental explains the name change, and might also explain why the Baharudeen name is not mentioned in online sources as an inventor. The Singapore Infopedia article was written in 2010, and the No Reservations episode aired in 2008. As far as I know, although the stall then shared both names, Baharudeen’s family wasn’t involved in the running of the business. It then makes sense if people tracing the history to the stall linked the invention of the dish only to the people currently running it; which happened to be Haji Kadir.

There was definitely something more behind the story, but considering the various parties’ reactions to questions about Sup Tulang’s origins, a lot of it can feel futile. Even Abu Bakar had laughed at me for researching Sup Tulang’s history, while my peers are apparently working on better things.

To the people laying claim to the dish, being the inventor of the dish is a matter of pride.

But what I’m concerned with is less about the truth than it is about how stories like Baharudeen’s are left untold.

I’m not here to take sides or tell you who invented what. Oral accounts of history are often unreliable even when taken directly from the source. Even assuming complete honesty, people don’t have eidetic memories; they interpret the past differently. Then there’s the vested interest of having the good marketing that comes with being the inventor of the dish.

It’s not uncommon for dishes to have multiple claims from inventors; the hamburger alone has at least six claims; Singapore’s Chili Crab has two different origin stories.

In the context of Sup Tulang, where a perfectly usable ingredient was thrown away, wasn’t it natural that people would eventually want to do something about it? Multiple people could have come to create the same dish, albeit in slightly different ways.

But in the end, does it matter? I can point to the poverty of cultural history and how having concrete knowledge of how hawker food solidifies a sense of national identity, citing scholarly articles from Brown and Mussell or Lily Kong. Or perhaps I start a philosophical debate on the merits of having an objective truth we can agree on.

That’s really for you to decide if it’s important, and not something I really give a shit about when sucking on the Foie Gras-equivalent of our local cuisine. If you ever want to try the dish for yourself, Golden Mile Food Centre is a good place to start.

Know something about a dish that we don’t? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.

The post This Mutton Soup You Didn’t Even Know Existed Was Invented In Singapore appeared first on RICE.