Moving plants mid-flower may go against the grain, but it’s a risk worth taking, says Stephen Lacey

The tolerance of plants is remarkable, not just to yo-yoing temperatures but to the rude incursions of gardeners. Flowering on a balmy morning, with the pleasurable tickle of a visiting bee on their pollen-coated anthers, suddenly they get a fork speared through their roots and they are catapulted skywards.

In a stuffed garden like mine, it is hopeless wandering around with bulbs in the autumn, trying to remember where there are spaces

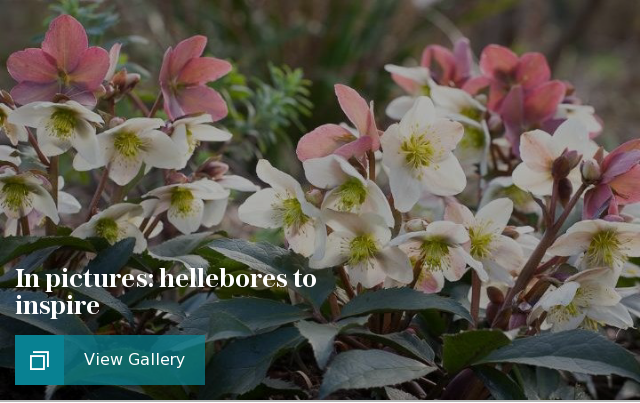

I have just been moving hellebores. Many growers do not consider this the optimal time for this job (which is early autumn), but it suits me. Moving plants around when they are in flower saves you having to rely on a dodgy memory: you see exactly where you want them and how they will look. So, if I think I can get away with it, I do.

I am moving the hellebores from under the beech trees where shade and drought have started to affect their performance. Vine weevils are also active there, I have been slow to realise; for a couple of years, hostas and ferns have been weakening, too. Now is the perfect time for a counter-attack with nematodes, and I have just sent off for some.

Meanwhile, a second wave of box blight has hit me, this time on the fat globes and 5ft-high cones that structure the beds around a small circular lawn. Early last autumn I came back from a week away to find grey patches, and within days it was spreading wildly. The worst-affected topiaries I extracted immediately; the remaining bushes I will monitor but fear they will also be gone by the year’s end.

It is a lightly shaded area, and as substitutes I thought I would try the looser evergreen shapes of Osmanthus delavayi – smaller and slower growing than O. x burkwoodii, but with similar tiny leaves and white flowers – and Tasmannia (formerly Drimys) lanceolata, which has attractive red stems and creamy flowers (it can be clobbered in a freakishly cold winter, so fingers crossed).

But some gaps I will leave open, and it is here I am installing the hellebores. After moving and/or dividing they invariably take a year’s sabbatical, but then bloom again robustly – especially with the TLC of chicken manure pellets and mushroom compost now, and a couple of liquid feeds in early September. With them are clumps of snowdrops and crocuses that I have been splitting for the past month or two. I have also started to add spring bulbs.

In a stuffed garden like mine, it is hopeless wandering around with bulbs in the autumn, trying to remember where there are spaces. Every spade inserted into the soil produces a ghastly crunch from a bulb already present. So I plant all my bulbs in small pots, and as they come into flower in the spring, I gently decant them. For big bulbs that like to grow deep, you can plunge the pots a few inches below ground for the winter, lined up in the veg patch, say; or you can just plant the bulbs a bit deeper when you turn them out of their pots, as I do.

A few dozen pots of Scilla siberica are already planted, united into rivulets of rich blue. They are echoing the pools of bicoloured blue grape hyacinth, Muscari latifolium, that has naturalised the other side of the path. And now I am putting in daffodils – the large ivory-coloured ‘Mount Hood’. I thought I would also try the damson allium, A. atropurpureum. Its cousins, ‘Purple Sensation’ and A. cristophii do well here in light shade – I wonder if it will, too…