I'd be lying if I said I wasn't anxious about the coronavirus – but I have faith in Britain

On Sunday morning, I woke to a view of lightly-frosted lake and snow-capped mountains, to an Austrian day glittering with promise. It was paradise, the long-postponed spa break I had promised myself after Brexit nearly drove me round the twist. We just got over that madness and now there was corona to worry about.

To hell with it, I thought. There could be months of doom ahead of us. I would take a holiday while I still could. Unfortunately, there was no treatment on the spa’s extensive menu that could massage away the gnawing feeling that I was in the wrong place at the wrong time. With the virus seeping across the map of Europe like poisonous green ink, I knew that I’d made the wrong call. Time to head home to wield the Dettol spray and guard my loved ones against invading microbes.

Turns out thousands of frantic British tourists had exactly the same idea. Eventually, I managed to find one seat on an afternoon flight from Salzburg to Luton. As I sat down, a man across the aisle asked the cabin crew if it could possibly be true. Had they really just closed the borders?

A stewardess laughed incredulously. “Yes, we were in mid-air when the Austrian Parliament made the decision,” she said, “so we didn’t know about it. I can tell you the ground crew looked surprised to see us when we landed.”

“But will they let us take off?,” the fretful man persisted. “Don’t worry, they’ll be glad to get rid of us,” she soothed.

Just then, a young family, who had run for the plane, collapsed into the row behind me with audible gulps of relief. “Thank God,” someone said. “Amen”, I mouthed silently. Just a few minutes later and we’d have been trapped – for what, weeks, months? We’d have had to use The Sound of Music escape method.

Taking off from a deserted runway into a plane-less sky felt oddly apocalyptic. The meringue peaks below had an eternal, majestic beauty, yet the world as we knew it was changed, changed utterly. We’d seen this disaster film a hundred times before, only this time we were the participants not the viewers.

History was no longer in the past; it was happening around me. I was on the last British flight out of Austria when, on 15 March 2020, she sealed herself off from the world and introduced a number of draconian measures to combat Covid-19.

Restaurants and bars would be closed, the entire population was told to self-isolate and “only have social contact with people you live with”, all young men who had done alternative social service (Zivildienst) in the past five years were called up for emergency duty (to enforce said draconian measures). Gatherings were limited to no more than five people. Even inside homes.

Bizarrely, I found myself thinking that the Trapp Family Singers, composed of seven children, would never have been able to sing at the Salzburg Festival if such stringent measures had been in place in 1938. Poor Greta, Kurt and Julie Andrews would need to self-isolate elsewhere.

It was hard to imagine the British submitting to such punishing restrictions, but then Austrians are used to following orders. Unlike the Italians who, when they were given advance warning that Milan would be locked down, jumped in their cars and drove South, allowing the Wuhan virus to hitch a ride.

Back home, life as we know it was also about to change, although that hadn’t sunk in yet. We weren’t ready or willing for it to sink in. I was still kidding myself I could get through the whole thing with anti-microbial wipes and Little Dorrit. Plans to advise those over 70 to self-isolate caused indignation among active senior citizens who, with some cause, considered themselves fitter than morbidly-obese 55 year-olds. Callers to The Jeremy Vine Show were mainly upset about the disruption to their social lives. Golfing while Rome burned.

Meanwhile, many of us were experiencing a weird generational inversion. I was nagging my mum to stay indoors and she was protesting that it was her life to live, just as she once nagged the teenage Allison to stay in and I told her I could do as I pleased. Try informing a member of the wartime generation that they need to minimise risk and you’ll probably get one of three responses. a/ “Fuss about nothing.” b/ “I want to enjoy the time I have left.” Or, my personal favourite, c/ “Well, you’ve got to die of something, haven’t you?”

If your parent’s earliest memory is of the Luftwaffe dropping a bomb on her grandparents’ farm because they’d missed their Swansea target, then appeals to take care tend to get short shrift. If you are a proudly self-sufficient (surely, maddeningly stubborn?) 83 year-old it’s not easy to hear yourself talked about as a member of a “vulnerable” group that needs to be quarantined for its own good. Former Home Secretary David Blunkett, aged 72, expressed the frustration of millions when he said, “Surely, we oldies should have the right to choose our own destiny? We understand the risks.”

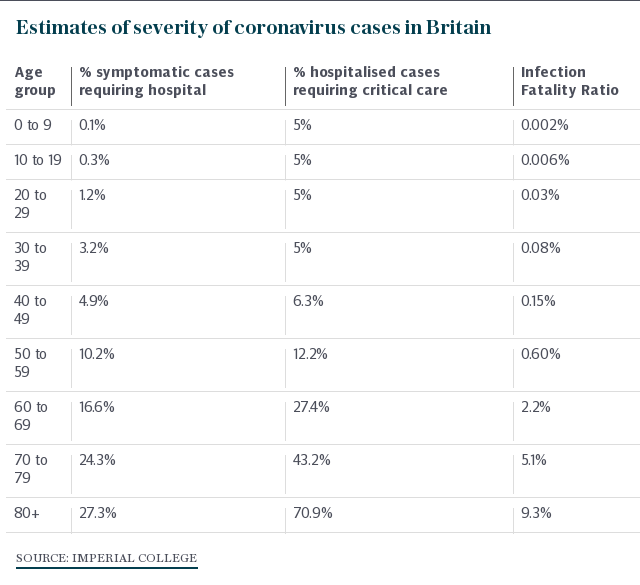

Unfortunately not, David. Those risks are everyone’s risks. The mortality rate for the Coronavirus in the over-80s is almost 15 per cent, 8 per cent for those aged 70-79, compared to less than 1 per cent for the general population. See page after heartbreaking page of obituaries in Italian newspapers filled with the faces of beloved Nonni and Nonne. No British government could possibly countenance 260,000 of its citizens developing a savage illness that required intensive care. Especially when there is only one free ICU bed in the United Kingdom, rumoured to be somewhere in Devon.

It’s not just that the coronavirus would wipe out a huge swathe of elderly people, although it would, it’s that so many desperately ill elderly people would wipe out the NHS. Normal influenza kills an average of 17,000 in England every year. That makes it sound like we’re over-reacting to this beastly Chinese interloper until you realise that those 17,000 people are already having to share just over 4,000 adult critical care beds. Quarantine will not be totally effective, but at least it will slow the rate of transmission, giving the health system more time to manage the load.

That’s why it can’t be a choice. Not any more. That’s why, on Monday, Boris, who is the most live-and-let-live fellow imaginable, had to make the previously unthinkable announcement that, from this weekend, a significant chunk of the population, now including pregnant women, would be confined to their homes for 12 weeks. The Prime Minister looked haunted, those hooded eyes have retreated further into their sleepless sockets. Haunted because he, who has access to all the research and mathematical modelling, can glimpse, with horrible clarity, the ghosts of tens of thousands of people whose very survival may depend on what he says and does.

The PM is torn between people shouting that schools must be closed and working parents begging that they stay open. (The modelling actually says that many more could die if they shut.) He’s torn between armchair critics fuming that other countries have cracked down faster and small-business owners whose life’s work could be destroyed in a week. Believe me, launching a national lockdown goes against every fibre of Boris Johnson’s being. But live and let live isn’t possible any more; not when it means live and let die.

So, if you are elderly, pregnant or in one of the other high-risk categories, please don’t see yourself as discriminated against or stigmatised. You are doing a huge service to the nation by temporarily staying indoors. Protecting yourself from the virus means that an asthmatic nine-year-old fighting for breath or a road-crash victim will be able to have the precious ventilator that you might otherwise need. Not for the first time, older Britons must make a sacrifice for the sake of their country.

We hear a lot about the threat to the elderly but, right now, it’s crucial to bear in mind that being “vulnerable” doesn’t just mean being physically at risk. Yesterday, my daughter and everyone else in the theatrical community either lost their job or had it “postponed”. (As a friend said wistfully, postponed is the new comfort word. Or crumb-of-comfort word.) Thousands of performers, front-of-house staff, directors, set designers, stage managers and musicians are devastated. Theatres going dark has a huge knock-on effect for bars, restaurants, taxis, hotels.

To add to this, the casual work that my daughter and so many of her generation rely on to earn money between proper jobs – waitressing, retail assistant, nannying – won’t be available as the hospitality industry collapses, shops shut and families hide away. My daughter says she’s afraid for an Italian waitress friend. Francesca can’t go home because her Corona-beset city is a no-go zone. If the café they both work in closes, Francesca will soon be both penniless and homeless. There are thousands in the same boat.

The vast invisible web of interconnected threads that bind us will soon become apparent as they start to unravel. Tony, who drove me to the airport, said business was down 90 per cent because his corporate clients were only allowing emergency travel. He was worried because he helps out his son’s family of five financially, and that can’t go on because his savings will soon run out. Yesterday’s announcement by the Foreign Secretary that all non-essential foreign travel is banned for 30 days may be a sensible precaution, but it makes a parlous situation for Tony, and everyone like him, even worse.

A friend who is pregnant with her first baby was hoping to work up until the end of May because she’s the main breadwinner. Suddenly, she is one of those who must self-isolate. Natalie and her husband are among millions wondering today how on earth they will pay the mortgage and the bills. I got a text from her last night. “I’m sure it’ll be OK, but we’re scared, Alli,” she said.

Of course she’s scared. Fear is a perfectly appropriate response to a situation which is unprecedented in our lifetimes. An advanced technological society is being held to ransom by a malevolent microbe.

During the 2008 crash, billions were used to prop up the banks. This time, we need to see that kind of money used to help small businesses, the self-employed who are cut off from clients, all those who have to stay indoors. Can I suggest Boris announces the immediate cancellation of HS2 with an estimated £106 billion diverted into a Corona Relief Fund? The nation would cheer. God knows, we need good cheer right now. A high-speed train looks like an extravagant irrelevance when the whole country is grinding to a halt.

Yesterday, the historian Peter Hennessy told the BBC that future historians would divide our age into BC and AC. Before Corona and After Corona. Is it really that bad? You shudder at the thought, yet what is already clear is that this crisis will stress-test our society, its institutions and communities, to the limit.

In an extraordinary speech to the nation on Monday, President Macron announced “absolute confinement” in France with only authorised food shops permitted. He committed a staggering 300 billion Euros to making sure that no company went under. “We will pay your rent, your utility bills,” he told the French people. It’s a promise that Boris Johnson may have to make sooner rather than later to prevent fear spreading faster than the epidemic.

Yesterday morning, as usual, I discussed this column with my brilliant editor, Vicki, who was working from home for the first time. Telegraph editorial conferences were being conducted via Skype. As we wait for the remarkable ingenuity of human beings to develop a vaccine that will put our world back to what it was – and it will, have faith, it will – we must all adapt our habits and our working practices to make the best of things. Thanks to the wonders of technology, your columnist and this newspaper will keep buggering on regardless. Please do email me (allison.pearson@telegraph.co.uk) or write a letter, and let me know how you’re coping. We will print the best stories.

I reckon that, over the coming weeks, we could do a lot worse than following President Macron’s advice: “Keep calm, keep contact with your loved ones, get news, read, take the time to come back to the essentials, to what is important.” To that excellent list I would only add, help your neighbours and volunteer as much as you can. Older people keep our voluntary services going. With them out of action for a while the rest of us need to rediscover a sense of community, which will be no bad thing.

As I write this, I am looking out of the window into the garden. There are primroses by the back door and the magnolia tree has burst into lucent, pinky life. (A movie star among trees, the magnolia.) The puppy is playing ball with the daughter, delighted to have her home. How strange it is. You wouldn’t know anything was wrong. You wouldn’t know that planes are deserting the skies, emergency economic measures are being rushed into place, that the world is at war with an enemy it cannot see.

We are on a journey without maps or lights and every bend in the road may bring something we can’t anticipate. It will be tough for a while, no doubt. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t anxious. But we have incredible scientists and medics on the case, we have a Prime Minister who, having had solemnity thrust upon him, will play that role with distinction. We have the amazing British people with their fundamental decency and lunatic relish for adversity and innovation. Spring is nearly here. Viruses come and go, but spring returns, always has, always will, bringing new life, new hope. Hang in there, everyone. You are not alone.

Read Allison Pearson at telegraph.co.uk every Tuesday, from 7pm