How Disney incorporates political messages into its children's films

Children’s stories have always had a habit of delivering subtle messages through fanciful tales and the Walt Disney Company’s offerings are no different.

The studio has been making statements about politics and society through its animated and live-action films for decades; its latest, Maleficent: Mistress of Evil, is no exception, and contains a not-so-thinly veiled attack on people who live a life of racial intolerance and seek to hurt those who look different from them.

With the movie out in cinemas this week, here’s a reminder of some other Disney films with political messages infused into their narrative.

Dumbo (2019)

It’s honestly shocking that Disney let Tim Burton get away with this unsubtle attack on, well, Disney.

The live-action remake of the 1941 animated original sees the wealthy owner of a Disneyland-esque circus/theme park, called Dreamland, buy a small travelling circus in order to get his hands on the flying elephant.

Read more: Disney Life to continue in UK while it awaits Disney+

Substitute Dreamland for Disney, the travelling circus for 20th Century Fox and Dumbo for the Avatar franchise and you’ve pretty much got the real-life story behind the Disney-Fox acquisition, which was finalised right around the time of this movie’s release.

Aladdin (2019)

While this live-action remake still fell victim to Orientalist reconstructions of the Middle East (e.g. Bollywood dancing and Indian clothing in what’s meant to be an Arab location) it did improve on the representation of Princess Jasmine compared with the animated 1992 original. Instead of being positioned merely as the exotic prize of Aladdin and Jafar, Naomi Scott’s iteration is a strong-willed politician fighting for the future of her country.

Her character is developed to show what she wants from life and for her people, and why she should be able to become Sultan despite archaic rules that try to subordinate her gender.

“My girl’s a politician, do you know what I mean?” Scott told People. “She’s not just there to look pretty.”

The Jungle Book (1967)

Not every bit of Disney’s political messaging has been a positive one. This animated classic (later also remade in live-action form) is based on Rudyard Kipling’s book of the same name and its allegory of British colonial rule in India. Mowgli and the humans represent the Anglo-Britains who colonised the country, while the animals of the jungle are the natives.

Growing up in colonial India, Kipling saw it as a place of happiness compared with England, and that attitude can be seen in Mowgli, who was raised in the jungle and prefers the company of animals to humans.

Read more: Rogue One’s Tony Gilroy signs up for Cassian Andor series

However, when he sees a pretty human girl (his attraction being a symbol of his growing up from boyhood into manhood) he ditches the animals that raised him in favour of returning to the humans. This perpetuates the notion that one should stick with one’s own kind, while King Louis’ song I Wan’na Be Like You suggests that the humans/British are superior to animals/Indians.

Not the most inclusive message.

Zootropolis (2016)

Speaking of racial discrimination, let’s talk about Zootropolis (AKA Zootopia). This animated film follows the investigation of a rookie cop Judy who is discriminated against by her boss because she’s a bunny and not seen as capable enough for the job. Then she, after seemingly solving the case of missing predators who went feral, uses scientific racism to suggest that predator biology is the cause of these savage transformations.

This leads to the increase of hateful speech and discrimination against predators throughout Zootopia until the prey-supremacist conspiracy is revealed and it’s proven that a drug is behind the feral transformations, not biology.

Zootropolis reflects the West’s history of bigotry and prejudice towards ethnic minorities but unlike the segregated attitude of The Jungle Book, it has a positive message of inclusion and equality.

Wreck-It Ralph (2012)

There are a lot of philosophical and social themes going on in Wreck-It Ralph but politically, it explores class division. Both Ralph and Vanellope are considered lesser because of their differences, and are forced to live in squalour as a result.

All they want to do is enjoy some success, whether it’s winning a medal to become a hero or winning a race to be accepted.

Over the course of their journey, they realise it’s who you are that counts, not how many medals you win – though in this economic climate, a few medals wouldn’t go amiss.

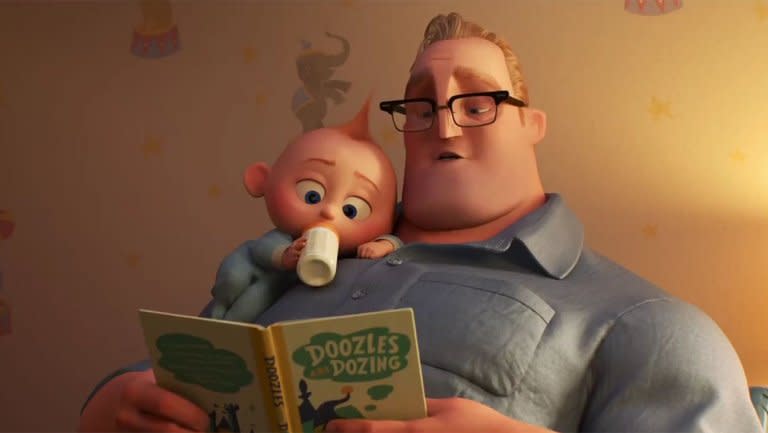

The Incredibles 2 (2018)

While The Incredibles looked at the economic ramifications of superheroes – who pays for them saving the day? – the sequel looks at the changing gender roles in the family home.

Elastigirl is asked to come out of superhero retirement, leaving Mr Incredible to become stay-at-home dad to his kids. He struggles with looking after his superpowered children, as well as the fact that he’s no longer the breadwinner in the superfamily.

Read more: Hidden meanings in classic kids’ films

The film flips the script of archaic gender norms to show that society shouldn’t be precious about keeping men and women in their stereotypical places.

Toy Story series (1995-2019)

The Toy Story franchise has long been a commentary on the concept of identity and whether we should let it define us. The first film follows Buzz coming to terms with his identity as a toy rather than an intergalactic space hero, while the first sequel centres on Woody being torn between being Andy’s toy or part of a Wild West collection.

Toy Story 3 looks at our changing identity from child to adult as we’re forced to take on new roles and responsibilities that life thrusts into our path. Then there’s Toy Story 4, which focuses on Forky’s existential crisis: being told he is one thing but believing he’s another.

At the same time, we’re also watching Woody taking that final big leap into adulthood by moving on and moving forward with his life knowing he’s no longer the beauty in the eye of his Bonnie beholder. He chooses to find a new identity by joining Bo Peep in freedom outside of someone’s possession.

Maleficent: Mistress of Evil is cinemas from Friday 18 October.