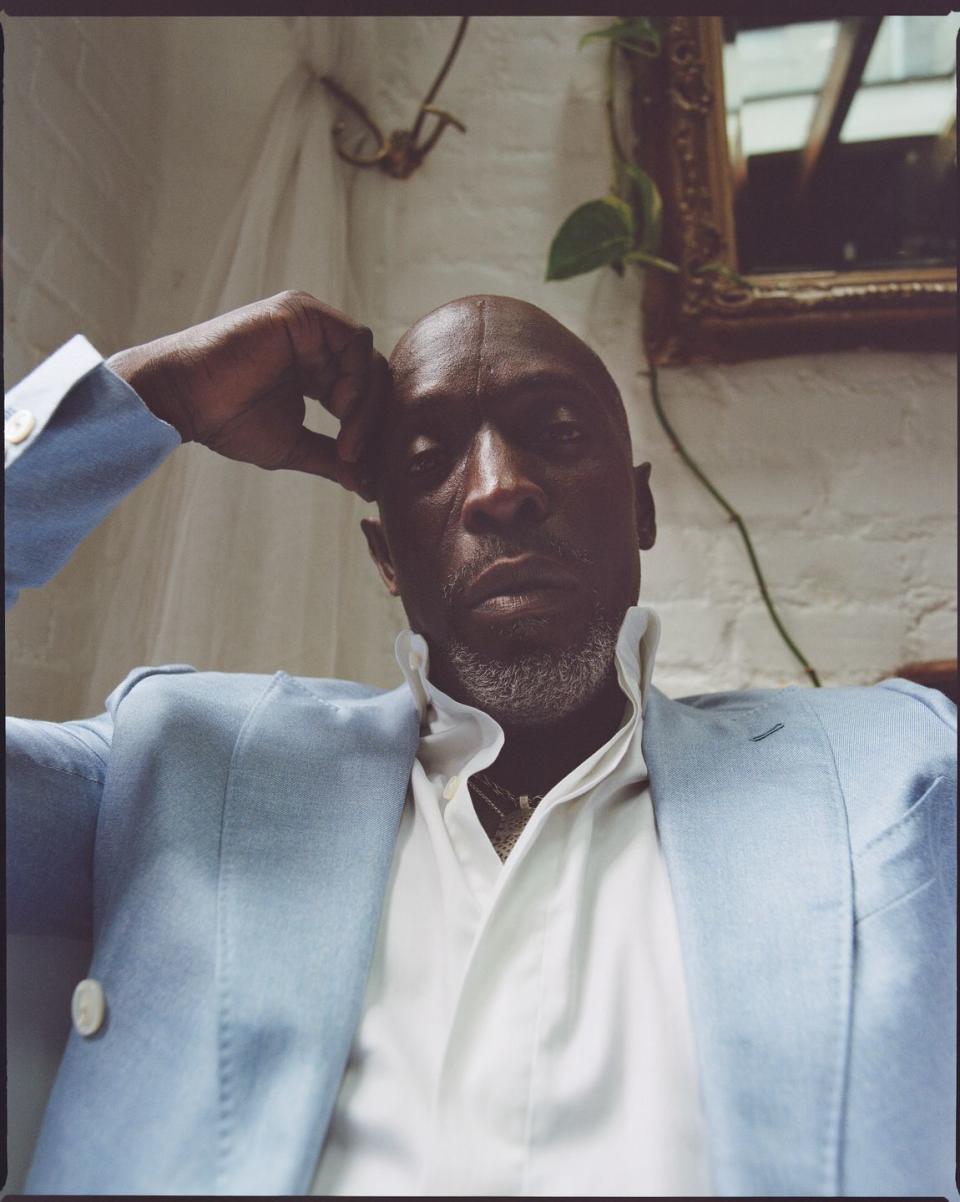

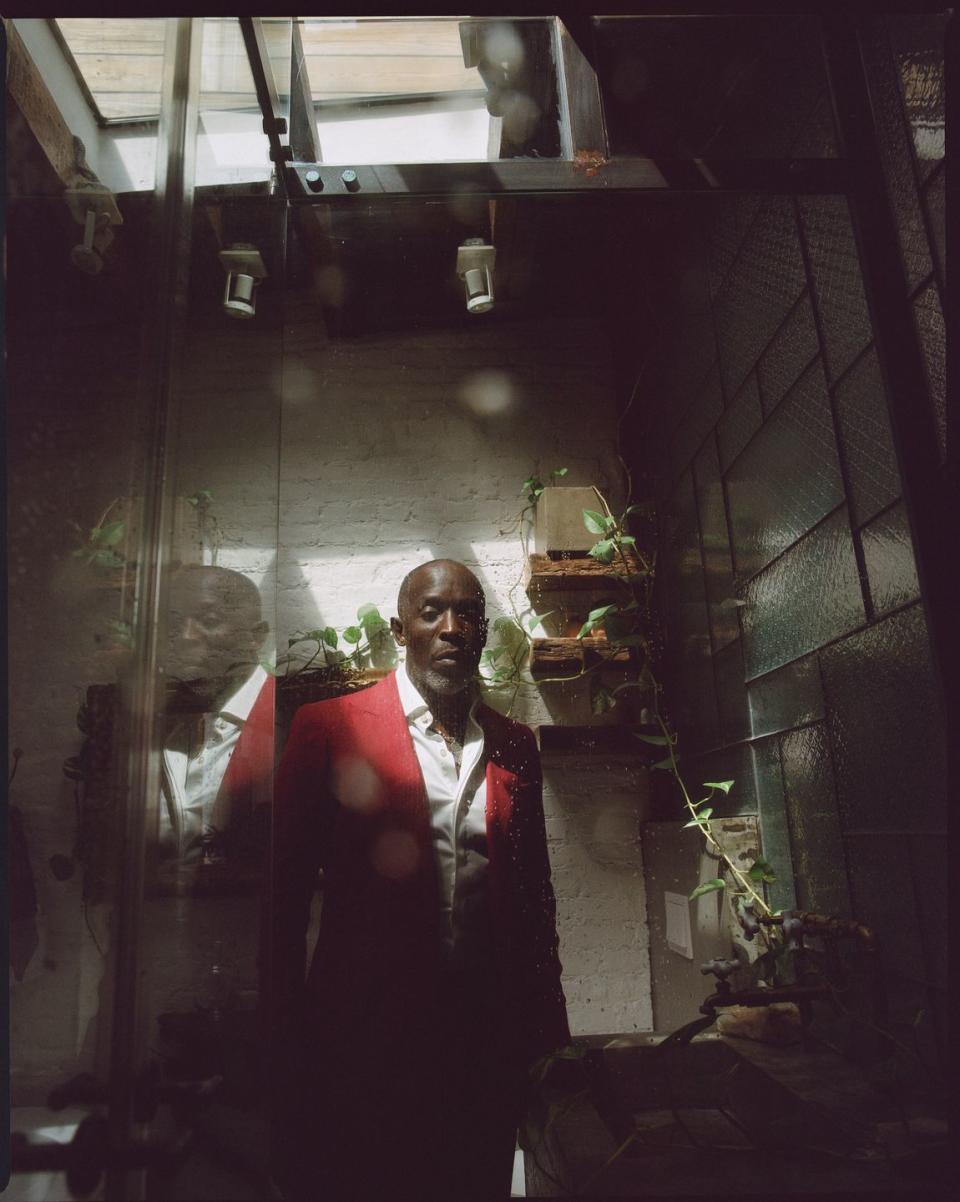

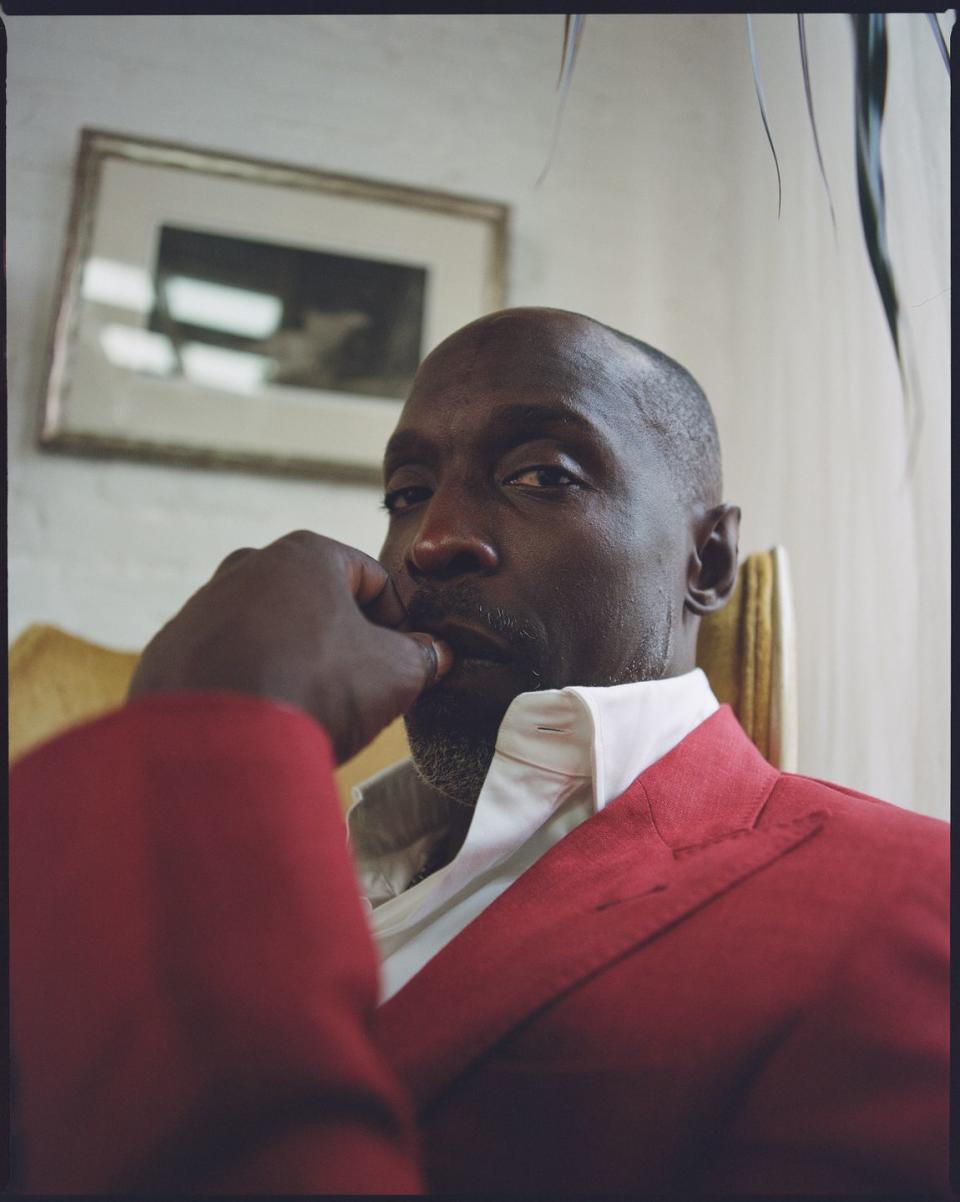

The Grace and Ferocity of Michael Kenneth Williams

New York, it’s said, is over, dying or already dead, shortly to sink into the sea. But Michael Kenneth Williams isn’t among the growing ranks of NYC pessimists. What would be the point of moving, anyway? The entire country is in crisis—and if he lived in California, he would have wildfires to contend with. To hear him tell it, there’s reason to be almost hopeful in the face of coast-to-coast to catastrophe. There’s nowhere to run, and we can only plant our feet more firmly in the ground we’re standing on. “I go down with this ship,” he says.

To television viewers, the city that Williams is most closely associated with is Baltimore, the setting of The Wire, the show on which he played Omar Little in a performance so beloved that even President Obama name-dropped it. These days, he’s playing a 1950s Chicagoan on HBO’s Lovecraft Country. But his feet are still planted on the sidewalks of his hometown, and even in the midst of all its turmoil, there’s no place the actor would rather be. It’s home to the people that inspire him and helped make him one of TV’s most powerful performers—an actor who, in role after role, plumbs the unexamined depths of Black masculinity.

On Lovecraft Country, the new HBO series based on a novel inspired by the works (and racism) of weird fiction writer H.P. Lovecraft, themes of gender and sexuality take a backseat to the show’s excavation of American racism. But through Williams’s character, Montrose Freeman, the father of the series’s protagonist, Atticus (Jonathan Majors), the series offers a bracing analysis of masculinity. Locked in a cycle of abuse—Montrose is an alcoholic who beat his son, just as he was beaten himself in childhood—Williams’s character could be easy to hate. But the actor has made a specialty of playing men who know both grace and ferocity, qualities he brings to Montrose to moving effect.

Williams’s character is at the center of one of the show’s most controversial moments so far. After Yamiha, a reanimated Two-Spirit Arawak person, is introduced in episode 4, Montrose slashes their throat, killing them brutally just moments after the character’s debut. “She represented magic and things that Montrose did not understand,” says Williams. “The only tool that he knew how to use in situations where he did not understand something was to get rid of it.”

It’s a difficult-to-watch moment, one that the series follows by offering a closer look at Montrose’s inner life. In the next episode, it’s revealed that Montrose is in a secretive relationship with Sammy, a male drag performer, with whom he attends a drag ball. It’s not the first time Williams played an LGBTQ character—Omar Little was also gay, and The Wire’s matter-of-fact handling of his sexuality was groundbreaking for its era. But Montrose is a man of the 1950s and can barely embrace much of his inner life, especially his stigmatized sexuality. He and Sammy may be semipublic at the ball, but the scene might not be a coming-out moment.

“Montrose never had the chance to come out of anything,” Williams says. “He was always told how to be. He was always told what a man is supposed to look like, feel like, and act like. And that’s what he aspired to do, even though it went against everything he wanted.”

When he finally finds freedom at the ball, Montrose demonstrates his perhaps temporary liberation using a universal visual shorthand for joy—he dances. In real life, Williams can pull off far more impressive moves than Montrose’s cautious shuffles. Before he was an actor, Williams was a backup dancer who worked with artists like George Michael and Madonna.

It may not have become his long-term career, but the catharsis and confidence that he gained from dance was a crucial stepping-stone from his early life as a “shy and corny kid” who grew up in Brooklyn to being one of his generation’s most commanding television actors.

Williams’s mother hails from the Bahamas, while his father is from the American South and lived through the Jim Crow era. Lovecraft Country’s depiction of racist affronts reflects aspects of his family history too painful to discuss. “I have family who were sharecroppers,” he says. “It wasn’t that my family sat at the dinner table and talked about it. Like most Black people do, we act like we are over it, past it. Never dealing with the trauma.”

One of his major breaks as an actor came when he was handpicked by Tupac Shakur to play his character’s brother in the 1996 film Bullet. It helped ignite Williams’s acclaimed career, one in which, with the facial scar he obtained during a barroom brawl on his 25th birthday, he’s often played men who’ve had hard lives, or who’ve been in contact with the penal system.

But despite being best known for playing tough guys, from Omar to gangster Chalky White on Boardwalk Empire to Rikers Island inmate Freddy on The Night Of, his real-life demeanor is incredibly gentle. (He had to seek out a lesson in firearms from a Brooklyn drug dealer after he was cast in The Wire—creator David Simon told The New York Times that when Williams was first handed Omar’s trademark shotgun, “He didn’t know which end was which.”)

Williams tackled the question of his repeatedly playing characters with broadly sketched similarities through an arresting 2018 short made by The Atlantic. In it, he discusses his career with multiple other iterations of himself. “I think you’re gonna always be playing some version of Mike,” a version of Williams dressed as Omar tells himself. “Gangster Mike, old-timey gangster Mike, southern gangster Mike.”

But in real life, there’s no devil on Williams’s shoulder trying to make him worried about the roles he’s performed. To him, the question of typecasting sounds like one that is “only being asked about Black actors.”

“ ‘Aren’t you afraid of being typecast?’ I’m like, ‘No, I’m afraid of not eating,’ ” he says. “This is my job.”

The suggestion seems loaded with the implication that the roles he plays are somehow undesirable, or that the characters he plays can be lumped into some undifferentiated mass of Black poverty and criminality. “Do you ask De Niro, Is he tired of being typecast, all the mob movies he’s made?” Williams wonders. The subtext is that a career made up of primarily playing low-income Black men is somehow not quite good enough.

Williams grew up in an apartment complex that’s these days known as Flatbush Gardens, though it was called the Vanderveer Estates when he knew it best. “We’re talking about a community of 59 buildings with, I think, 42 apartments each,” he says. “That’s a lot of people that I had access to growing up.” He could spend the rest of his career exclusively playing characters based on people in his neighborhood, and there would be thousands of stories to tell.

“I will not allow Hollywood to stereotype or to desensitize my experience growing up in the ’hood,” says Williams. “This is my job as an actor, to show the integrity, to show the class, to show the swagger, to show the danger, to show the pain, to show the bad choices. Those things exist in everyone’s community. But no one’s asking those actors if they’re afraid of being typecast.”

After fielding the question enough, Williams came to a realization: “It’s not about whether they think I’m being typecast. It’s about not allowing them to typecast me.”

Last year, Williams received an Emmy nomination—his fourth, and no wins yet, somehow—for his portrayal of Antron McCray’s stepfather Bobby on Netflix’s When They See Us, Ava DuVernay’s acclaimed depiction of the Exonerated Five saga. It was a secondary role but one filled with some of the series’s most emotionally devastating material. Though all of the five young men had their lives stolen after being falsely convicted of rape in 1990 (they were not exonerated until 2002), the imprisonment destroyed the previously close relationship McCray had with his stepfather, who naively instructed the boy to tell police what they wanted to hear before temporarily abandoning the family amid his grief and guilt. He died of kidney failure before he could be truly reconciled with his son.

The shows couldn’t be more different, one a fantastical adventure horror and the other directly recounting a real-life tragedy, but both of them find Williams diving into the well of Black men’s emotional pain. It’s a topic that’s rarely examined publicly. “We are made to swallow pain and trauma and to act like it doesn’t exist,” he says. “And it’s debilitating. We impose it on ourselves. We get it imposed upon us. What is masculinity? What is male sexuality? What is vulnerability? What does being a man really mean?”

Williams and I spoke the day after NBA players—largely Black men, all of whom symbolize one of the pinnacles of American masculinity—went on strike in the wake of Jacob Blake’s shooting by Kenosha police. In the days before digital fans, Williams could often be spotted in the front row of Knicks games, and his support of the players’ economic protest for racial justice was full-throated. “I think it is time,” he says. “In sports and Hollywood, the amount of money they’ve made off of our stories and our talent is unimaginable.” But he was also aware of the irony: Even as he praised the NBA players who refused to walk onto the court, he was speaking to a journalist. He was doing his job.

“I questioned, ‘What does me going back to work look like?’ ” Williams wondered. Performers “get snatched out of our community, and then we’re thrust into this financial success, and then we’re pampered. And it’s awkward.”

One of the ways that Williams maintains his ties to his Brooklyn community is through service. He’s working with NYC Together, an organization that supports the city’s youth. This summer, the organization sponsored 45 youngsters for summer jobs that found them planning and executing COVID-19 educational campaigns. Those are a small fraction of the nearly 40,000 jobs that the city cut from youth-employment programs amid its pandemic-induced budget crisis, but summer work can be life changing for kids from underserved communities—one study found that the city’s summer employment program was correlated with a reduced likelihood that participants would end up incarcerated or die prematurely. “They all graduated,” Williams says proudly of the NYC Together youngsters. “Every kid that signed up for that program.”

He’s also working on a clothing and accessories line called Kings County. (Kings County is synonymous with Brooklyn.) One of the brand’s T-shirts depicts an iconic Brooklyn scene, with a young, pre-fame Biggie Smalls freestyling on a city street. When Williams and I spoke, the brand was planning a back-to-school giveaway that would offer backpacks to kids in his old neighborhood.

“I’m excited when I go into my community and I see my people,” says Williams. “How they shout me out when I’d be riding my bike through the city streets. All they do is give me so much hope, so much hope.”

You Might Also Like