From five billion to zero: the passenger pigeon – and other beautiful animals driven to extinction

Here are 10 iconic species no longer on Earth, largely thanks to humans.

1. Passenger pigeon

A nomadic bird that could reach speeds in excess of 60mph, the passenger pigeon was once a common sight across North America, from the Great Plains to the Atlantic Coast. At one point they numbered up to five billion, making them the most populous species of bird on the planet.

That was until the arrival of Europeans, who hunted them on an industrial scale for cheap meat. Tens of millions were slaughtered each year and the last wild passenger pigeon was seen in 1901. Cincinnati Zoo was home to the last captive bird, Martha, which died in 1914 - it is now stuffed and found inside the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

“Passenger Pigeons once migrated through Canada, the United States, and the Gulf of Mexico in numbers so huge that they darkened the sky,” says the website of the American Natural History Museum. “One flock was described as ‘a column, eight or ten miles in length... resembling the windings of a vast and majestic river.’ In 1808, [another] flock of passenger pigeons in Kentucky was estimated at more than two billion birds.” John James Audubon, a French-American naturalist, described how a migrating flock passing over his head blocked the sun for three straight days.

It has been argued that the passenger pigeon’s vast 18th and 19th century population was “ephemeral”, and unsustainable - they were destructive to the forest, cracking trees under their collective weight and covering the ground with excrement - but human activity, including the destruction of their food sources, westward expansion, and overhunting, wiped them out entirely.

Where it roamed: North America, to the east of the Rockies

Closest living relative: They are closely related to Patagioenas, a genus of New World pigeons, of which there are 17 species.

2. Dodo

Perhaps the most famous extinct species, the dodo - endemic to Mauritius - was also wiped out in just a few decades. The first recorded mention of the flightless bird was by Dutch sailors in 1598; the last sighting of one was in 1662. It owes much of its fame to its appearance in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

But relics of the bird are surprisingly scant. On its website the Natural History Museum says: “Despite the abundance of the dodo in Mauritius during the 17th century, very little remains in museums as evidence of its existence. There are a few partial skeletons of the bird; a skull in Copenhagen, a beak in Prague, a foot at the Natural History Museum and a head and foot in Oxford. The one known complete stuffed bird was in the collection of John Tradescant who bequeathed it to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Here, the specimen was allowed to rot, so that by 1755 the directors of the Museum consigned it to the bonfire. It is thanks to the dedication of one curator from the Ashmolean Museum that the head and foot were saved and these are now in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.”

Where it roamed: Mauritius

Closest living relative: The Nicobar pigeon, found in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India

3. Western black rhinoceros

This subspecies of the black rhino once roamed sub-Saharan Africa, but fell victim to poaching. Its population was in the hundreds in 1980, fell to 10 by 2000, and just five a year later. Surveys in 2006 failed to locate any and it was declared extinct in 2011. It followed the extinction of two other black rhino subspecies: the southern black, around 1850, and the north-eastern black, in the early 20th century.

There was more bad news for Africa’s rhinos earlier this year when Sudan, the world’s last male northern white rhino, died, leaving only two females of its subspecies alive in the world.

Where it roamed: The last survivors were found in Cameroon

Closest living relative: The black rhinoceros, native to eastern and southern Africa, is critically endangered. There were 65,000 in the wild in 1970. That fell to 2,300 by 1993, but conservation efforts have helped raise the population to around 5,000. One of the best places to see them is Kenya.

4. Pyrenean ibex

Extinct since 2000, the Pyrenean ibex - a subspecies of the Spanish ibex - was once common to the Pyrenees but its population fell sharply in the 19th and 20th centuries. The reasons behind its decline remain unknown. In 2003 it briefly became “unextinct”, after scientist managed to clone a female, but it died minutes after being born.

Where it roamed: The Pyrenees

Closest living relative: Two of the four subspecies of the Spanish ibex still exist: the Western Spanish ibex, found in the Picos de Europa, and the Southeastern Spanish ibex, common in the Sierra Nevada. Southern Spain is also home to Europe’s rarest cat. The Iberian lynx – an elegant, fox-sized cat with tufted ears – is confined to the wildest corners of Andalucia, including Andujar and Doñana National Parks, where it stalks the scrubby hillsides for rabbits.

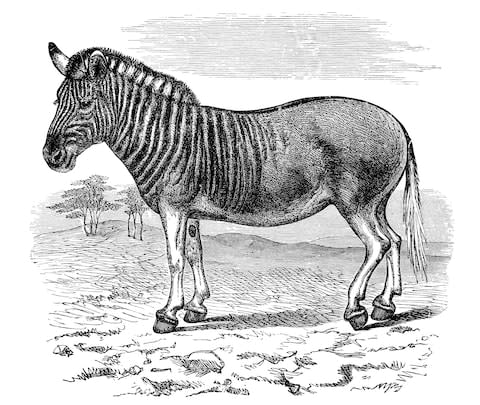

5. Quagga

A subspecies of plains zebra, with stripes only on the front half of its body, the quagga lived in South Africa. It was heavily hunted after Dutch settlers arrived and found it competing with domesticated animals for forage. It was extinct in the wild by 1878; the last captive specimen died in Amsterdam in 1883.

Where it roamed: South Africa

Closest living relative: Burchell’s zebra, which thrive in Namibia’s Etosha National Park.

6. Tasmanian tiger

A shy, nocturnal animal and similar in appearance to a dog (but with a stiff tail and abdominal pouch), the Tasmanian tiger was rare or extinct on the Australian mainland before the arrival of the British, but survived on Tasmania. Hunting, disease, the introduction of dogs and human encroachment all contributed to its demise there. The last known specimen died in Hobart Zoo in 1936.

“Known as the Tasmanian wolf, Tasmanian tiger, zebra dog, pouched wolf, and marsupial dog, among others,” says the website of the American Museum of Natural History. “A quick look at the animal explains the confusion. Shaped like a dog, striped like a tiger or zebra, pouched like an opossum, and reputed to behave like a wolf, it became many different creatures in the popular imagination.”

Where it roamed: Tasmania

Closest living relative: The Tasmanian devil is still found on the island, but is endangered.

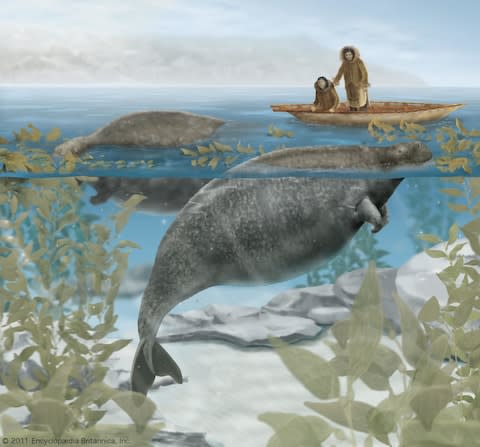

7. Steller’s sea cow

The largest mammals, other than whales, to have existed in the holocene epoch, the Steller’s sea cow reached up to nine metres in length but was hunted to extinction in 1768, within 27 years of its discovery by Europeans.

Georg Wilhelm Steller described its hide as “more like unto the bark of an ancient oak than unto the skin of an animal” and “almost impervious to an ax or the point of a hook.” Its blunt forelimbs were also of particular interest. “There are no traces of fingers, nor are there any of nails or hoofs,” he wrote. “With these he swims, as with branchial fins; with these he walks on the shallows of the shore, as with feet; with these he braces and supports himself on slippery rocks; with these he digs out and tears off the algae and seagrasses from the rocks, as a horse would do with its front feet; with these he fights.” A complete skeleton can be seen in Helsinki's Natural History Museum.

Where it roamed: Its last population surrounded the uninhabited Commander Islands, part of the Aleutian Islands in the northern Pacific.

Closest living relative: The dugong, found in coastal areas of the Indian and south-west Pacific oceans, and the manatee (also known as sea cows), found in the Caribbean (West Indian manatee), West Africa (West African manatee), and the Amazon (Amazonian manatee). All are considered vulnerable.

8. Woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth, which reached heights in excess of three metres and weighed up to six tonnes, coexisted with early humans, who used its bones and tusks for making tools and dwellings and also hunted it for food. Small populations survived on St Paul Island, off the coast of Alaska, and Wrangel Island, in the Arctic Ocean, until 5,600 and 4,000 years ago, respectively.

Where it roamed: Arctic regions of Asia and North America

Closest living relative: The Asian elephant, itself considered endangered

9. Great auk

Once common to the North Atlantic, including the coast of Britain, the great auk - like penguins, though unrelated - was flightless, and clumsy on land, but an agile swimmer. Demand for its down contributed to its elimination from Europe, while early explorers used it as a convenient food source. It has been extinct since at least 1852.

London's Natural History Museum houses a specimen from the island of Papa Westray. It says: “The flightless great auk, Pinguinus impennis, is one of the most powerful symbols of the damage humans can cause. The species was driven extinct in the 19th century as a consequence of centuries of intense human exploitation.”

Where it roamed: The North Atlantic

Closest living relative: The razorbill, found in the North Atlantic, including Iceland

10. Pinta Island tortoise

This subspecies of Galápagos tortoise is widely considered extinct, with the last known specimen - Lonesome George - dying in 2012. A recent trip by Yale University researchers, however, suggested that Isabela Island, the largest of the Galápagos, could still be home to the species.

Where it roamed: Pinta Islands, The Galápagos

Closest living relative: Giant tortoises can still be seen on seven islands in the Galápagos, and the Aldabra atoll, in the Indian Ocean.