From fishermen to ravers: why we can’t kick the bucket hat

Once you start looking for bucket hats, they are everywhere. In just a week, I see them on public transport. On Arsenal right-back Hector Bellerin’s Instagram account. In JW Anderson’s Uniqlo collaboration. In the Teddy Pendergrass documentary. In a Kader Attia photograph outside the Hayward gallery. On Rita Ora’s head in a snow shower. On the Christian Dior catwalk. In the pub on Saturday afternoon. They come in towelling, in banana-printed fabric, with logos, without logos, in khaki, in neon pink, priced from £6 to more than £400. Round, soft and with a brim coming down to the wearer’s eyebrows, the bucket is both deeply fashionable and universal. It is, if you will, an everyhat.

Asos say its sales of bucket hats have risen by 343% in a year, with a £10 design with an orange smiley face the most popular on the site. Kangol has produced bucket hats since the 70s. Globally, orders for its washed bucket are up 339% in spring 2019 compared with spring 2018, while its Bermuda Casual – the trademark robust towelling shape – is up 113%. The bucket hat is now a regular on the catwalk – along with Dior, it has featured in Craig Green, Prada and Burberry shows. Meanwhile, Rihanna is the modern bucket hat’s patron saint. She has worn designs in snakeskin, tropical print, PVC and khaki.

But the bucket hat isn’t just about now. It has a history that takes in everything from inhospitable weather to soldiers and pop culture. Stephen Jones, the British milliner who designed the bucket hats on the Dior catwalk, says it can be dated back to “the most ancient of hats. If you look back to the 14th century there are, essentially, bucket hats. You have something that goes over your head to protect your hair, and the brim, which is to protect your face.”

Nova Scotia fishermen at sea off Grand Banks.Photograph: Peter Stackpole/Getty Images/The LIFE Picture Collection Creative

The sou’wester is one of the bucket’s more recent ancestors. Designed with a longer brim at the back, and made in waterproof fabric, it was named after strong south-westerly winds, and worn by fishermen working off the coast of Cape Cod. Amber Butchart, the author of Nautical Chic, says sou’westers “were a fashionable choice during the cloche craze of the 20s”, appearing in Vogue and Jean Patou’s collection.

Like the Breton or the Aran knit, the sou’wester shows how fishermen’s clothes “formed the basis for chic classics … This style legacy is still with us today.”

A military version of the bucket hat first appeared in the 40s as standard issue uniform for the Israeli Defence Force, to protect soldiers from the desert sun. Another was worn by US soldiers in Vietnam, immortalised by Lt Col Henry Blake in the TV series M*A*S*H*.

Timothy Godbold, the author of Military Style Invades Fashion, points to an incarnation in early 20th-century Ireland, where farmers wore wool or tweed versions. “They were useful because the high lanolin content made them water-resistant,” he says. “They were also washable and easy to store in your pocket.”

Although the bucket hat’s convenience and protective design made it popular among a wider public, it was initially far from a fashion statement. The bucket hat was the signature of the hapless ex-navy man Gilligan in Gilligan’s Island, the 60s American sitcom about a group of castaways. Its fate seemed to be set when golfers took it up as an alternative to the flat cap.

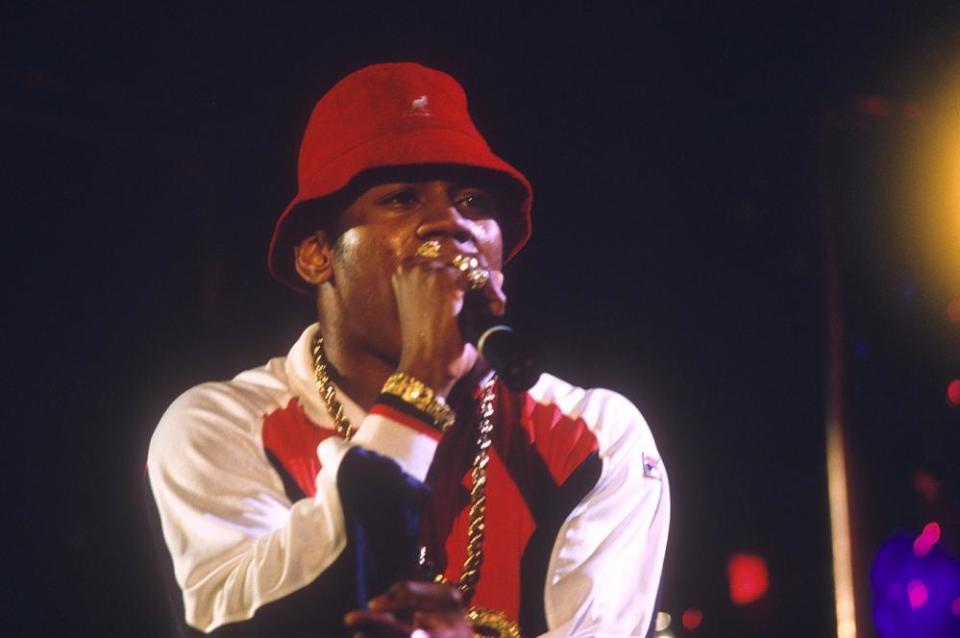

But buckets were soon discovered by a very different demographic – the burgeoning B-boy and girl scene in the Bronx in the late 70s. Eric Arnold, a hip-hop historian and consultant on Oakland Museum’s 2018 exhibition Respect: Hip-Hop Style & Wisdom, says they became “a way to identify yourself as a cultural practitioner or devotee of hip-hop”. LL Cool J and Run DMC would later wear them.

LL Cool J rocking a Kangol in 1986.Photograph: Farhad Kanuga/REX/Shutterstock

Wilson suggests that this uptake of the golfer’s hat could be seen as a form of subversion, challenging the ideas of what was appropriate style for a community made up, by and large, of young people of colour living in cities. “I think for some, it signified disruption of the status quo by this upstart culture which repurposed things,” he says. “The same thing happened to Timberland and Polo, even MCM, Louis Vuitton, and Gucci – brands which were adopted as urban street fashion.”

As hip-hop moved from the Bronx to worldwide phenomenon in the late 80s, the bucket hat came with it. Along with Kangol, Stüssy was a crucial brand – its bucket hat with the double “S” was endorsed by the Beastie Boys and, according to co-founder Frank Sinatra Junior (no relation to the singer), hats accounted for 20% of the brand’s business by the late 80s.

It was the Stüssy bucket, and others by similar streetwear brands, that was adopted on the rave scene in the UK. The crowd at the Stone Roses’ 1990 Spike Island gig was a sea of bucket hats, and the band’s drummer, Reni, wore one, too. For King Adz, streetwear expert and author, it’s this that makes the bucket hat a classic.

“It’s the archetypal raver’s hat,” he says. “The more northern, the better. I think of Spike Island, Centreforce FM tapes, mud on my Travel Fox boots from a rave in a field just outside Elstree in 1989.”

It’s these blue-chip subculture moments that feed into the bucket’s current success. Sean Leon, global marketing director of Kangol, puts the bucket’s current resurgence down to nostalgia among 19- to 24-year-olds. “I think today’s generation is probably discovering the early-80s history and moving into the 90s for the first time,” he says. “They’re looking back on it in the way I would look back to the 70s.” It’s not just the LL Cool J association that works. Leon mentions modern celebrities: “Anderson Paak wore one on Saturday Night Live, A$AP Ferg wears the cotton ones and so does Gully Guy Leo, a young streetwear influencer.”

3 guesses what’s in my bag, go💼

A post shared by Leo Mandella (@gullyguyleo) on Feb 4, 2019 at 11:24am PST

Gully Guy Leo, a British teenager whose real name is Leo Mandella, has 715,000 followers on Instagram, and wears a bucket hat teamed with tiny sunglasses, the kind of statement that would turn heads in a nightclub. This is the bucket hat’s latest incarnation, according to Jian Deleon, editorial director at streetwear website Highsnobiety. “It’s probably more popular as a clubwear or nightlife accessory than for its intended purpose of keeping the sun out of your eyes,” he says.

The everyman status of the bucket hat means this is only where it is now – as a classic, it will no doubt change again. “It evokes senior citizens, elder statesmen of hip-hop and British football hooligans alike,” says Deleon. “It’s a very specific item with a wide range of connotations.” With fashion exploring a more inclusive outlook, perhaps it works precisely because it can’t be pinned down.

“It can be a fashion item but it’s also a universal item in the way a T-shirt is,” says Jones. “The best way to put on a bucket hat is almost to slap it on your head and not look in the mirror.”