In control: why fetish fashion has returned

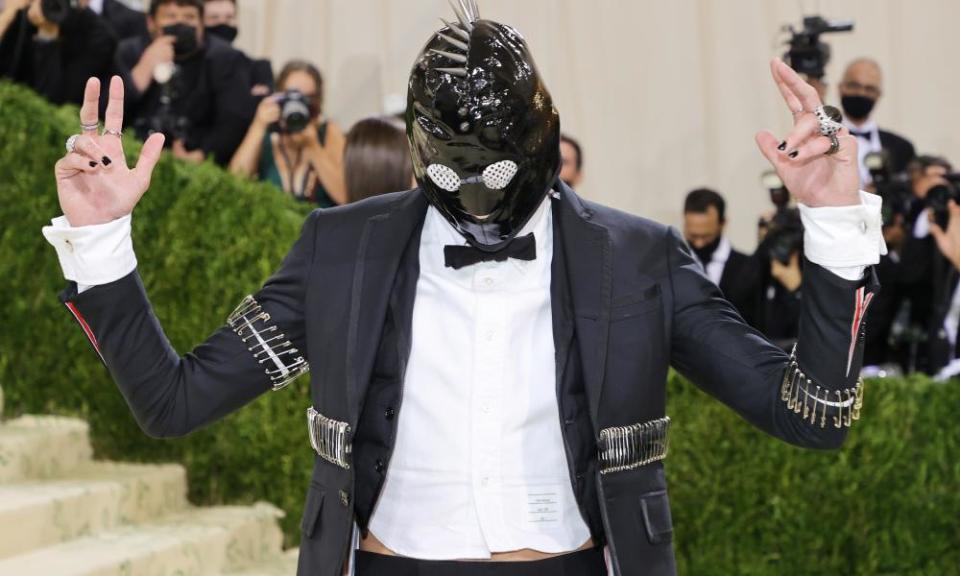

This week, 40 plus years after Vivienne Westwood first opened her SEX boutique, Kim Kardashian and Madonna have both shocked with fetish-leaning outfits. Madonna appeared at the MTV VMAs dressed in an Atsuko Kudo latex ensemble, leather gloves and cap, while Kardashian wore a face-obscuring, all-black Balenciaga look at the Met Gala (an intentional nod to Kanye West’s recent style). At the same event, Gossip Girl actor Evan Mock wore a studded gimp mask from Thom Browne. So why have these niche outfits gone mainstream?

Historically, fetish wear has emerged into the daylight after economic downturns or major events, such as the first and second world wars, and Lou Austin, co-owner of the fetish site MegaPleasure, believes it’s linked to a collective trauma. “I wouldn’t be surprised if this pandemic triggers a resurgence of mask-wearing both in bedrooms and on the runways as a nod to the shared tedious trauma we’ve all been living through the last year or so,” she says.

“The re-emergence of fetish fashion is in part a reaction to lockdown,” says Professor Andrew Groves who curated Undercover, an exhibition which looked back at pandemic mask wearing in public spaces. “For the last 18 months, we’ve all been in a strange BDSM relationship with the government,” he says, “which has controlled our bodies, forcing us to wear masks and told us who we can kiss or touch. Adopting fetish clothing as fashion can be interpreted as a desire to switch the relationship, take back control and show them who is really in charge.”

The term “festish” was first defined by the French author Nicolas Edme Restif de la Bretonne in the 18th century. “(It) became popular in the 1920s with French company Yva Richard selling hats, lingerie and shoes,” explains Jennifer Richards, a tutor at the Royal College of Art. “They were also notorious for their creation of a studded cone steel bra,” she says, a precursor to Jean Paul Gaultier’s cone bra made famous by Madonna. Richards adds that fashion designer Rudi Gernreich’s work in the 1960s was hugely influential on designers such as Helmut Lang who popularised the fetish look. “Gernreich’s work was a reaction to the overt sexualisation of the body of the period,” she says, “he sought to remove the stigma of shame and embrace the body in its totality.”

The spectre of fetish fashion has been part of our modern visual vocabulary, whether that’s the outfits in WAP or Billie Eilish’s March Vogue cover. Groves believes our continuous exposure to such items make them less shocking. “[Their] meaning is diluted,” he says, singling out the gimp mask. “[Its] progression from fetish to fashion object by Westwood in the 1970s, then reinterpreted by [fashion designer] Margiela in the 1990s and now worn by Kanye West exemplifies [that] its force has been weakened as a result of its unending dissemination.”

Still, Richards believes there is an important message to be taken away from the wearing of these clothes. “These garments allowed for both transformation and empowerment,” she says. “If we look back to Freud’s original theory, then fetishism is about control. In a time where we are trying to be more open and transparent around sex, these garments may be a way to begin to take back the control for ourselves.”