From cage to conservation: the reinvention of Australian zoos

The elephant temple at Taronga Zoo on the lush north shore of Sydney harbour does not look like a great home for giant mammals. Its oriental pastels and concrete floors speak of a zoo as a place of oddities from far-flung places. A place for gawking and gift shops.

Which, of course, it was.

“It’s not a history that anyone’s particularly proud of today,” says Cameron Kerr, chief executive of Taronga Conservation Society, which runs Taronga Zoo and Western Plains Zoo. Contemporary standards shouldn’t be used to judge past behaviour, he says, but historical zoo practices do not reflect modern expectations.

“Coming to the zoo for a good day out and seeing the animals, I want to know that they’re not just here for my entertainment,” he says.

Entertainment remains important, but its form has changed. A little way from the old elephant temple (no longer used by elephants) is the zoo’s newest exhibit, the Sumatran tiger enclosure. To enter, visitors must first board a virtual cargo plane flight to Way Kambas National Park, in Indonesia, during which they look out the windows to see deforestation caused by the palm oil industry and listen to an Indonesian guide extoll the virtues of sustainable palm oil and the personal responsibility of visitors to shop ethically.

Visitors wind through the green exhibit, clustering at vantage points to see the three tiger cubs and adults sleep and stalk. Before they leave, they pass through a mock supermarket where they can check the WWF palm oil rating of a range of foods, and then send an email lobbying brands to do better. Then, they pass the gift shop.

Related: Rare white-cheeked gibbon born at Perth zoo

Some 20 million people visited zoos and aquaria in Australia and just over 2.1 million in New Zealand in 2017, and indications are that this number has been increasing since. Zoos from Perth to Sydney have been reporting record visitor numbers.

But has the tiger really changed its stripes?

Zoos globally have long been subject to criticism over animal welfare standards. The documentary Black Fish years ago highlighted problems with keeping orcas in captivity, and there remains opposition to the keeping of cetaceans and other large, social and migratory species – such as gorillas or elephants – in human care.

“There’s a lot of zoos in the world and an awful lot of them are no good,” says Elaine Bensted, chief executive of Zoos SA, which operates Adelaide Zoo and Monarto Safari Park. “We should be either trying to improve them, or get them shut down. We’re lucky in Australia that we don’t have very many of what I call the ‘really bad zoos’. A good zoo should have an absolute focus on animal welfare, on conservation and be absolutely focusing on their own environmental sustainability practices.”

For many zoos this means holding fewer animals. Taronga’s tiger enclosure was once home to three other species. Adelaide Zoo is phasing out Nile hippo and giraffe.

“We’ve been really clear that you need to think carefully about what species you hold if you don’t have a big footprint,” Bensted says. “Absolutely there is still a role for city zoos – they play an incredible role in education, as well as tourism – but you have to recognise that if you’ve got a small site, we’re not going to try to hold every single species so people can come and see it.”

However, as zoos are reliant on visitors to fund their operations, they do have to consider holding popular, charismatic species. Bensted says Adelaide Zoo has decided to continue to hold pandas, although they’re large, because they are popular with visitors, but also because the zoo was confident the animal’s enclosure provided them with a good standard of welfare.

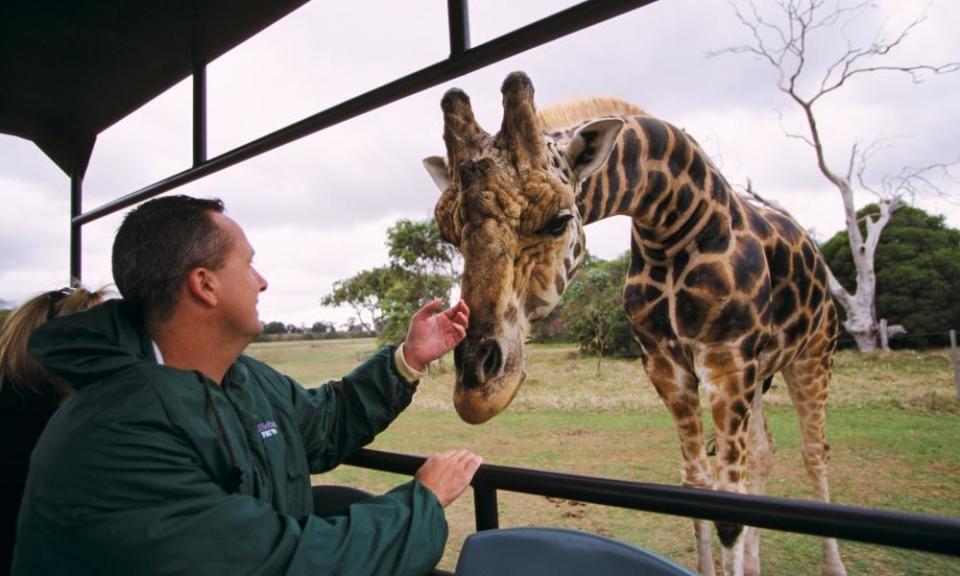

Bensted’s Monarto Safari Park has also joined a number of other large zoos, including Taronga, Western Plains and the National Zoo and Aquarium, in offering high-end overnight accommodation. The luxe lodgings offer a new revenue stream. Kerr, who launched the Wildlife Retreat at Taronga last month with rates starting at $790 for two people, says overnight stays also result in more pro-environmental behaviours from guests, who spend more time with keepers, animals and conservationists. Taronga already hosts 38,000 overnight visitors a year, many of them local.

In Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific, the Zoo and Aquarium Association accredits zoos and aquaria in a process focused on animal welfare standards. The association has plans to extend its accreditation process to include conservation, biosecurity and sustainability. Accreditation runs on a three-year cycle and works on the “five domains” model of animal welfare, considering the animals’ nutrition, health, environment, behaviour and mental state.

“It’s about agency and how an animal experiences what it experiences,” says Nicola Craddock, the association’s executive director. “It’s quite holistic and very much based on a specific animal, from that animal’s point of view.”

Related: Melbourne zoo hatches plan to save southern corroboree frog

Dr Ali Chauvenet, a conservation scientist from Griffith University, says zoos can become a refuge even for animals that may not be suited for captivity, because the world outside is no longer safe for them. “We don’t want a world where all we have is animals in zoos,” she says. “It is outside threats which are bringing us here.

“Big primates are highly stressed in their natural habitat. We haven’t figured out how to protect them in the wild. Even though putting them in zoos can be stressful, we are also contributing a lot to their persistence because we have them in zoos.”

As the world tilts towards what has been termed a sixth mass extinction, zoos in some quarters are acting as a last line of defence against the extinction crisis. So much so that it’s become part of their branding. Zoos Victoria’s tagline is “fighting extinction”.

But how much of this conservation talk is PR spin? Peta Australia has called it the “conservation con”. “I’ll be honest and say it may have been a bit of greenwashing way back when,” says Taronga’s Kerr. But, he says, things have genuinely changed.

Many conservationists and wildlife groups spoken to by Guardian Australia agree: in a world where species are dying off at an alarming rate, zoos have a role to play. Taronga has bred and released more than 50,000 animals into the wild. It has committed to protecting 10 critically endangered species from extinction over the next 10 years. Zoos Victoria has its sights set on 27.

“Zoos have really evolved from a display to entertain people with oddities, to these bastions of conservation,” Chauvenet says. “They are definitely already part of trying to fight this extinction crisis.”

The World Wildlife Fund’s chief conservation officer, Rachel Lowry, says all zoos are not equal but good zoos are having an impact.

“WWF recognises that zoos play an increasingly important role in providing an ark for threatened species, which has proven to be vital in preventing the extinction of many species,” she said. “Conservation-focused zoos can buy precious time to allow conservation interventions in the wild to take place prior to reintroduction.”

For many species, time is running out. When Cameron Kerr became CEO of Taronga a decade ago, the team would be called up about once a quarter to identify a new disease outbreak among wildlife in the state (it has a catalogue containing 35 years of wildlife disease). “Now it’s at least two a month,” he says.

They have been able to intervene successfully. When a pair of kayakers found large numbers of dead Bellinger River turtles on the river, the Taronga team were sent up to the mouth of the river, where the disease had not yet spread, and grabbed 12 turtles. It was a new disease killing the turtles that had lived there for millennia, and within five weeks there were no wild breeding adults left.

The captured turtles were quarantined, bred and then released back into the river. But it was a close call.

Taronga’s director of welfare, conservation and science, Nick Boyle, says the zoo has been trying to get ahead of the extinction game. “I think in the past we’ve been seen as the last line of defence in extinction, and sometimes it’s too late,” he says.

“We are there to respond in emergency situations so we are always going to have a role to play in an imminent extinction crisis, but we’re increasingly trying to position ourselves as an agency, or industry, to contact early in turning around the trajectory of the species.”

The World Association of Zoos and Aquaria has set a goal of all zoos reaching a 3%-of-budget spend on ex-situ conservation work. Taronga calculates its spending on field conservation work at about 11.5% of its budget. Zoos SA is at about 6%, and Bensted says she would like to see all zoos protecting in the wild the species they keep in captivity. SeaLife Sydney wasn’t able to put a figure on its “out of gates” conservation work, but says educating visitors about marine animals and issues could be viewed as conservation work.

Kerr, however, says judging a zoo by its conservation spend is too simplistic. “I think we should be talking about impact. It is about what happens to the 2 million people who pass through the zoo gates. Twenty-first century conservation is about people, not animals.”

Kelly Miller, an associate professor of environment and science at Deakin University, says: “So many of us live in cities and urban environments so we have less and less opportunity to connect with nature. A good zoo – one that prioritises animal welfare – can give people an opportunity to learn about other species in very meaningful ways.

“It is sometimes difficult for people to care about conservation in another part of the world or even in their own local environment if they have no opportunity to learn about why it matters.”

It is not just about scooping turtles out of a river that’s killing them. It’s about delivering environmental messages in a world where environmental messages are increasingly polarising. And doing it with a friendly face – and a sustainable palm-oil packet of chips.