The bizarre history of vaccine certificates

In 1716, Giacomo Pagliano left the Sicilian port of Messina on a ship laden with goods bound for the Adriatic coast city of Ancona. Sicily had become an important stop on trade routes criss-crossing the Mediterranean, and this departure was no different to the likely dozens on any given day.

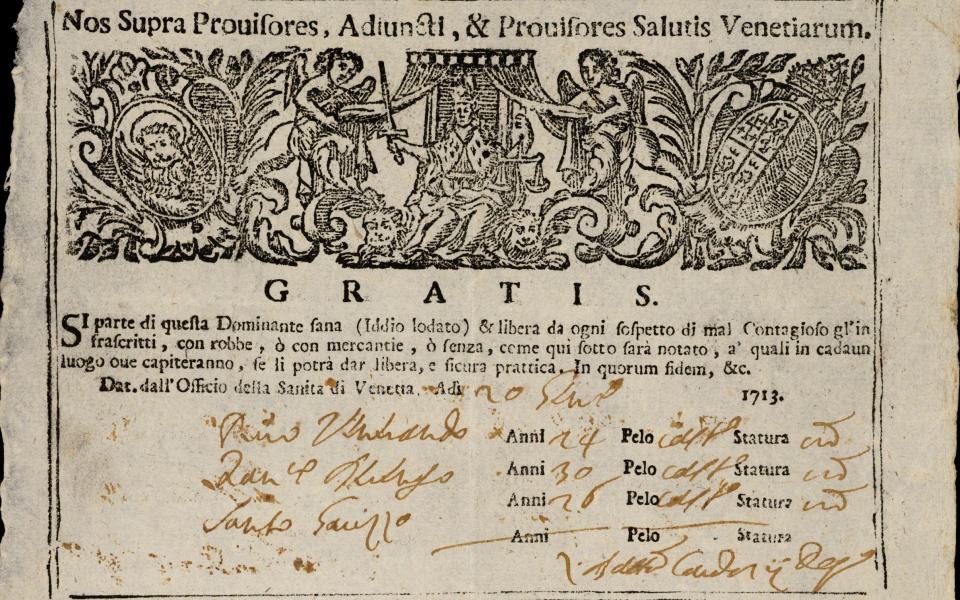

With his cargo, Giacomo carried with him a rather ornate document explaining that he and his crew were “free from diseases” and permitting entry to various docks without the need to quarantine. With a devastating outbreak of the bubonic plague still in the memory of Italian society from the previous century, this certificate would help traders go about their business safe from concern they might spark a fresh wave of infections.

These 'fede di sanita' carried by shipmen in the early 18th century in and around Italy were some of the earliest examples of what we might now describe as a vaccine passport.

Documents relating to immunity or good health were used prior to the fede di sanita. Indeed, some Londoners required such a certificate of wellness signed by the Lord Mayor if they wished to leave the city during the Great Plague in the 17th century. But the Italian measures seem to be the first linked to travel.

And of course, they were not the last.

In India, under British rule, authorities decided to make proof of vaccination from the plague a necessity for pilgrims travelling to the town of Pandharpur in colonial Bombay province. Then the attention turned to different diseases.

As the 19th century became the 20th in the US, a smallpox outbreak led states to require proof of vaccination from the disease for entry into everything from schools to places of work. Though paper certificates were the preferred method, due to concerns over forgeries, authorities instead began to rely on the physical mark of vaccination.

Michael Willrich, a history professor at Brandeis University, Massachusetts, and author of Pox: An American History, told History television network: "The vaccine recipient would start to feel quite sick, usually with a fever and a very sore arm. The vaccine site would become more and more irritated, a scab would form, fall off, and what was left behind was a small scar roughly the size of a nickel. And that’s how you’d know that the vaccination took."

This is not to say the entirety of the public played ball. Beyond those opposed to the idea on legal or ethical grounds, some who were not prepared to receive the vaccine at all gave themselves a look-alike scar with a simple scalpel.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya, a professor in the history of medicine at the University of York and director of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Collaborating Center for Global Health Histories, says the need for proof of smallpox vaccination also arose in Asia around the same time.

"When there were outbreaks in South Asia people from there were not allowed to board ships, for instance, to Aden or Great Britain, or Mecca for the Hajj, without government-issued smallpox vaccination certificates," he told NPR. "These matters were considered even more urgent in the second half of the 20th century after the introduction of air travel."

The International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation was formed in 1933, became the responsibility of the WHO on its conception in 1946 and was adopted into the International Health Regulations we know today in 1969.

Initially, the globally recognised certificates were to cover cholera, plague, smallpox and yellow fever, but cholera was dropped in 1973 when it was deemed that vaccination against the disease could not prevent its spread.

It was smallpox that the International Certificate of Vaccination (ICV) claimed as its greatest scalp, helping eradicate the disease by 1980; the relevant ICV was scrapped the following year.

As it stands the only ICV remaining in use is for yellow fever, known as the yellow card and perhaps the one that is most familiar to British travellers. The NHS recommends that, beyond gaining the document for countries that require it for entry, it is worth considering vaccination before travel to parts of sub-Saharan Africa, South America, including Brazil and Argentina, and Trinidad in the Caribbean.

There have been other standalone requirements issued by individual countries. In 1994 Saudi Arabia required pilgrims bound for Mecca to be vaccinated against meningococcal meningitis, while there are plenty of recommendations made of Americans by the State Department and of Britons by the NHS.

The future of any vaccine passport for Covid-19 still looks uncertain, with accepted documents existing in different forms, but primarily on smartphone apps. One thing for certain is they will never look as beautiful as Italy’s 18th century, decorative fede di sinata.